Monetary policy decisions are typically made by committees, and not by the central bank governor alone. The reason is, presumably, that groups make better decisions than individuals. Groups pool knowledge and information, and provide safeguards from extreme preferences and views.

But groups have minds of their own (Pettit 2004). They can easily make self-contradictory judgements, even if each individual member of the group never makes self-contradictory judgements. One type of self-contradictory group judgement leads to a ‘discursive dilemma’ as the policy decision will depend on whether the group votes on the premises for the decision or the decision itself. Furthermore, effective communication can be difficult when there is a discursive dilemma.

To see how it works, let’s look at two examples.

Monetary policy committees face a discursive dilemma

Let’s start with quantitative easing, the central bank purchase of government bonds in the secondary market.

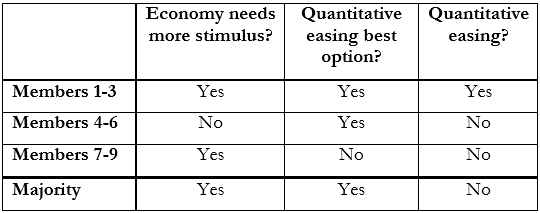

Suppose all members of a monetary policy committee (MPC[RB1] ) agree to implement a quantitative easing programme if two ‘premises’ are fulfilled: (i) the economy needs more stimulus; and (ii) quantitative easing is the best option. If the members’ judgements are as in Table 1, the majority judgements become self-contradictory and the MPC faces the following (discursive) dilemma:

- Voting on the conclusion – ‘the conclusion-based voting procedure’ – gives a ‘no’ to quantitative easing.

- Voting on the premises – ‘the premise-based voting procedure’ – results in a ‘yes’ to quantitative easing (a ‘yes’ on both premises implies a ‘yes’ to quantitative easing).

What should the decision be? Arguably, both approaches seem reasonable.

Note also that it becomes difficult to provide a majority-supported economic argument or explanation for the conclusion-based decision. The majority judgements on the premise cannot be used, as they are inconsistent with the ‘no’. The judgements of members 4-6 or members 7-9 can be used, but these can hardly be said to represent the MPC view or majority view. And which of these two alternatives should they use?

Table 1. Quantitative easing and the discursive dilemma

Let’s move to an example that shows that the problem extends beyond the binary (yes/no) situation above.

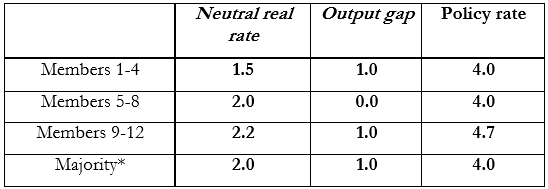

Suppose that the MPC was instructed to set policy according to a Taylor rule, as recently proposed by some members of the US House of Representatives. To keep things simple, assume that inflation is at its target level at 2%. Then the appropriate policy rate is given by

policy rate = 2+neutral real rate+0.5output gap.

Table 2 gives a combination of individual judgements, or estimates, that lead to a discursive dilemma. Here, the majority views on the neutral rate and the output gap together with the Taylor rule yield 4.5, while the majority policy rate is 4.0. Consequently, the MPC faces a discursive dilemma. What should the decision be? And, if they vote directly on the policy rate, what should the economic story explaining that decision be? The majority view cannot be used.

Table 2. The Taylor rule and the discursive dilemma

Note: * We have here assumed that the outcome of a majority vote over the preferred alternatives for each variable is the median of these alternatives, i.e. the ‘median voter theorem’ holds.

The discursive dilemma is a very general phenomenon. It is easy to give examples with other voting rules and different connections between the premises and the conclusion. Readers interested in general characterisations of when examples can and cannot be given should consult List and Polak (2010) (binary judgements) and Claussen and Røisland (2010, 2014) (non-binary judgements). List (2012) provides a non-technical survey for binary judgement aggregation.

Voting on premises is preferable

The following question naturally arises: Should MPCs vote directly on the policy rate – as most do – or should they vote instead on the underlying premises for the decision? We see two reasons why voting on the premises can be preferable.

- The first is that voting on premises tends to lead to better average economic outcomes.

With linear rules like the Taylor rule above, the two procedures result in the same average outcome. However, with other rules – or if there is disagreement about both the parameters and variables in a linear rule – the procedure matters. In a recent paper, we look at MPC decisions in a standard New Keynesian monetary policy model and find that the premise-based procedure results in the best average outcome (Claussen and Røisland 2014). Only if MPC members are overconfident about the quality of their judgements on key parameters (e.g. the slope of the Phillips curve) could the conclusion-based procedure perhaps result in a better average outcome. In that case, however, conclusion-based decisions work as a second-best solution to the overconfidence problem. It would have been better to avoid overconfidence in the first place and use the premise-based procedure.

- The second reason is that premise-based decisions make communication easier and better.

Communication is easier because unlike the conclusion-based procedure, the premise-based procedure always gives a majority-supported economic explanation for the decision. Communication is better because the premise-based explanation for the decision is the most precise one as it has the lowest average judgement errors on the premises (Claussen and Røisland 2015).

Partially premise-based decisions are possible

Truly premise-based decisions can be difficult in practice. It is cumbersome and time-consuming to vote on premises and the MPC might not even agree what the premises there are.

However, partially premise-based decisions seem possible. With partially premise-based decisions, the MPC distinguishes issues on which it wants to have a representative MPC view and issues on which it does not. It first votes on the first set of issues. Then each member takes these MPC judgements as given, makes his/her own judgements on the remaining issues, and arrives at a preferred policy. Then the MPC votes on policy. To explain the decision, the MPC communicates the MPC judgements on the first set of issues and the decision. The explanation will not be complete, but it will be consistent with the decision. Furthermore, the elements of the story that are communicated reap all potential pooling gains and represent the ‘centre of gravity’ judgements on these issues. We discuss partially premise-based decisions in another recent paper (Claussen and Røisland 2015).

What do MPCs actually do and what should they do?

In practice, there are probably elements of conclusion- and premise-based procedures, perhaps in a somewhat blurry mix, at all central banks.

The Federal Open Market Committee of the US Fed seems to use a strongly conclusion-based procedure. They discuss premises, but apart from the statements in the press releases they publish no majority view on premises. They decide on policy by voting on policy.

MPCs of central banks that produce an inflation or monetary policy report are probably more premise-based in their decision-making, even if they vote on policy in the end. We can think of it as a partially premise-based procedure, as described above. Members first decide on the main elements of the report, and then take these as given when arriving at a preferred policy. The MPCs of the Bank of England and Sveriges Riksbank seem to use this approach. Former deputy governor of Norges Bank, Jan Qvigstad, explicitly describes the Norges Banks procedures as premise-based (Qvigstad 2011).

However, having a common report does not guarantee that the procedures are premise-focused. We could have a system where the MPC votes or decides on policy first, and then constructs the report and/or a common economic explanation afterwards. This will correspond to a conclusion-based procedure where the economic explanation is ‘constructed’ to fit the final decision. As explained above, this is not a good solution. It is difficult, it can lead to somewhat arbitrary explanations, and the explanations are not the best ones.

Our conclusion is that MPCs that have a common report should make sure to use at least a partially premise-based procedure. For MPCs without a report (with common views) the communicational issue is less of a problem, but the results in our paper (Claussen and Røisland 2014) suggest that these MPCs can also gain from being more premise-based in their decision-making.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Executive Board of Norges Bank or Sveriges Riksbank.

References

Claussen, C A and Ø Røisland (2010), “A Quantitative Discursive Dilemma”, Social Choice and Welfare 35(1), pp. 49-64.

Claussen, C A and Ø Røisland (2014), “The Discursive Dilemma in Monetary Policy”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics 116(3), pp. 702 – 733.

Claussen, C A and Ø Røisland (2015), “Explaining interest rate decisions when the MPC members believe in different stories", International Journal of Central Banking 11(2), pp. 41-64.

List, C and B Polak (2010), “Introduction to Judgment Aggregation”, Journal of Economic Theory 145(2), pp. 441- 466.

List, C (2012), “Judgment Aggregation: A Short Introduction”, in U. Mäki (ed.), Philosophy of Economics, Handbook of the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 13, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Pettit, P (2004), “Groups with Minds of their Own” in Frederick Schmitt (ed.), Socializing Metaphysics, New York: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 167-93.

Qvigstad, J F (2011), “On Making Good Decisions”, Norges Bank Occational Paper No. 43/2011.