Evidence of a leaky pipeline for women in academic economics is not new. Studies of economists from the 1980s and 1990s showed that women were significantly less likely to be promoted to tenured positions than men (Ginther and Kahn 2004, McDowell et al. 2001). Economics became substantially less male-dominated during this period, however, with the share of women in top PhD-granting departments more than doubling at all ranks in the 20 years between 1972 and 1993. More recently, this growth in female representation in the economics discipline has stalled. The share of female assistant professors and PhD students has remained roughly constant since the mid-2000s.

Little consensus has emerged as to why improvement in women’s status in economics has slowed in recent decades. In our paper (Lundberg and Stearns 2019), we first document trends in the gender composition of academic economists over the past 25 years. We then review the recent literature on other dimensions of women’s relative position in the discipline and assess evidence on the barriers that female economists face in publishing, promotion, and tenure. We propose that differential assessment of men and women is one important factor in explaining women’s failure to advance in economics, reflected in gendered institutional policies and apparent implicit bias in promotion and tenure processes.

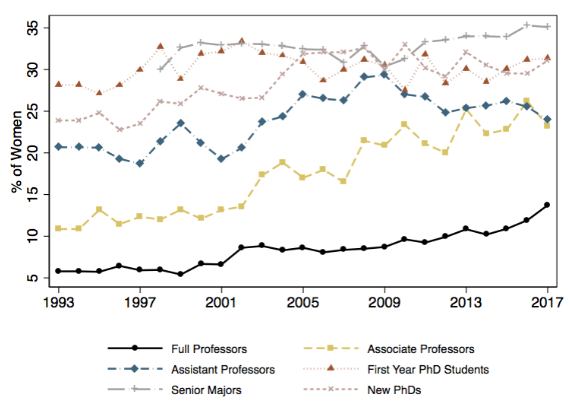

Figure 1 shows the share of women in 43 top PhD-granting departments (these departments grant approximately two-thirds of US PhDs and can be consistently tracked over time) from 1993 to 2017. The share of female full and associate professors increased from 6% to 13% and 11% to 23%, respectively. The pattern is different for assistant professors, however: the share of women increased from 20% to 29% between 1993 and 2009 but has since decreased to 24%, leaving little net growth at junior ranks over the past 24 years. There has also been little improvement in female representation among first-year PhD students or senior undergraduate economics majors. Progress towards gender equality at the intake levels of the profession appears to have ceased, while women’s representation at senior levels continues to rise, fuelled for now by the entry of women into academic economics in past decades.

Figure 1 Representation of women among first-year PhD students, new PhDs, and faculty by rank for 43 PhD-granting departments, 1993-2017

Source: Authors, using data from the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) and the Universal Academic Questionnaire for PhD-granting departments from 1993 to 2017.

The share of female faculty decreases with rank, as in most academic disciplines, and economics remains solidly within the lowest group in terms of female faculty shares at all levels, alongside physics, math, and engineering, and far below the biological and other social sciences. Unlike other academic disciplines, however, the promotion gap in economics cannot be fully explained by differences in productivity or family characteristics. Ginther and Kahn (2014) conclude that “economics is the one field where gender differences in tenure receipt seem to remain even after background and productivity controls are factored in and even for single childless women”. Economics has also made less progress than other math-intensive fields over the past 25 years in terms of improving gender equity in income, promotion, and job satisfaction (Ceci et al. 2014).

In many academic disciplines, women have fewer publications than men on average (Ceci et al. 2014, Ginther and Kahn 2004). A leading hypothesis for the lower productivity of female academics is that women have more intense domestic responsibilities and, in most science, engineering, technology, and mathematics fields, publications by single childless men and women are not significantly different. But in economics and the physical sciences, there is a significant gender gap in productivity among the childless as well. With productivity differences that appear unrelated to family demands and unexplained, persistent differences in tenure rates, the gender gap in economics appears to be distinct from that in other disciplines.

If women’s relative failure to advance in departments of economics cannot be explained by the gender gap in productivity, the possibility of differential treatment arises. An emerging literature in economics is reporting evidence that female economists face substantial barriers throughout their careers.

Early-career female economists may be adversely affected by limited access to the mentoring and social networks that support research activities. Men and women have different research collaboration and co-authorship networks (McDowell et al. 2006), and women’s co-authorship patterns are distinct from those of men in ways that are predictive of lower output (Ductor et al. 2018). When papers are sole-authored, male and female economists receive similar credit in terms of their impact on tenure decisions (Sarsons 2017). However, women receive significantly less credit than men for co-authored work, particularly when they co-author with men. This contrasts with evidence from sociology, where Sarsons finds that men and women benefit equally from co-authored work.

Women and men in economics may also face different experiences throughout the publishing process. The empirical evidence for outright discrimination against women in manuscript review is mixed (Ferber and Teiman 1980, Blank 1991, Abrevaya and Hamermesh 2012). More recently, Card et al. (2018) study referee recommendations and editorial decisions at four leading economics journals and find no evidence of differential gender bias. But both male and female referees appear to hold female authors to a higher standard (as measured by future citation counts), resulting in a substantial difference in the probability that female-authored papers are rejected. Hengel (2017) finds that economics papers written by female authors spend six months longer under review at one top journal, although they are objectively more readable. These differences in co-authorship networks and potential biases in the publishing process may both contribute to the substantial underrepresentation of female authors in top journals (Hamermesh 2013).

Even policies that have been supported on the grounds of gender equity may create biases against women’s success. Antecol et al. (2018) examine the effect of gender-neutral tenure-clock stopping policies, which allow assistant professors who have children to extend their tenure clock. They find that these policies substantially increase the probability that men get tenure in their first job, but reduce the probability that women do. Effects on publications suggest that fathers use the additional time on the tenure clock more productively than mothers.

What can explain the unique challenges that women seem to face in economics? An adversarial and aggressive culture within academic economics may play a role, though its impact is difficult to quantify. Anecdotal evidence suggests that women may choose to go into less male-dominated fields based on early experiences with toxic environments that men are more likely to tolerate. While it is difficult to obtain quantitative estimates of outright harassment, there are many reports of women in economics experiencing inappropriate behaviour in job interviews, seminars, meetings, and at conferences (Shinall 2018). Recent work also suggests that gender harassment is a serious problem in academics more broadly (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018).

Differences in productivity between men and women likely drive some of the gender gaps in economics, though it is important to recognise that productivity gaps can arise both because of the different choices men and women make and also because of the differential constraints they face. However, the fact that gender gaps in professional outcomes conditional on productivity are larger in economics than in other academic disciplines suggests that the disparate assessment of men and women may be another important factor in explaining female disadvantage. If this is the case, as recent evidence seems to indicate, continued progress toward equality in academic economics will require a concerted effort to remove opportunities for bias in the hiring and promotion processes. Continued action to do so can be justified both on the basis of simple fairness and also on the benefits of creating an environment where equal work yields equal rewards.

References

Abrevaya, J, and DS Hamermesh (2012), “Charity and favoritism in the field: Are female economists nicer (to each other)?”, Review of Economics and Statistics 94(1): 202–207.

Antecol, H, K Bedard and J Stearns (2018), “Equal but inequitable: Who benefits from gender-neutral tenure clock stopping policies?”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Blank, RM (1991), “The effects of double-blind versus single-blind reviewing: Experimental evidence from the American Economic Review”, American Economic Review 81(5): 1041–1067.

Card, D, S DellaVigna, P Funk and N Iriberri (2018), “Are referees and editors in economics gender neutral?”, working paper.

Ceci, SJ, DK Ginther, S Kahn and WM Williams (2014), “Women in academic science: A changing landscape”, Psychological Science in the Public Interest 15(3): 75–141.

Ductor, L, S Goyal and A Prummer (2018), “Gender and collaboration”, Cambridge-INET Working Paper 1807.

Ferber, MA, and M Teiman (1980), “Are women economists at a disadvantage in publishing journal articles?”, Eastern Economic Journal 6(3/4): 189–193.

Ginther, DK, and S Kahn (2004), “Women in economics: Moving up or falling off the academic career ladder?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 18(3): 193–214.

Ginther, DK, and S Kahn (2014), “Academic women’s careers in the social sciences”, in A Lanteri and J Vromen (eds), The economics of economists: Institutional setting, individual incentives, and future prospects, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hamermesh, DS (2013), “Six decades of top economics publishing: Who and how?”, Journal of Economic Literature 51(1): 162–172.

Hengel, E (2017), “Publishing while female: Are women held to higher standards? Evidence from peer review”, Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 1753, Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge.

Lundberg, S, and J Stearns (2019), “Women in economics: Stalled progress”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, forthcoming.

McDowell, JM, LD Singell Jr and M Stater (2006), “Two to tango? Gender differences in the decisions to publish and coauthor”, Economic Inquiry 44(1): 153–168.

McDowell, JM, LD Singell Jr and JP Ziliak (2001), “Gender and promotion in the economics profession”, ILR Review 54(2): 224–244.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018), Sexual harassment of women: Climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Sarsons, H (2017), “Gender differences in recognition for group work”, working paper.

Shinall, JB (2018), “Dealing with sexual harassment”, CSWEP News, Issue I, American Economic Association Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession.