“Industrialise Africa” is one of the African Development Bank’s top five priorities for the continent. And in November 2020, the African Union, together with the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), kicked off its 30th Africa Industrialisation Week.

Some economists have called into question the primacy of manufacturing. For example, Gollin (2018) questions whether there is anything special about manufacturing and whether our emphasis on manufacturing as a path to development reflects our lack of imagination in relation to other possible paths. Several researchers have pondered services as an alternative pathway to development. Yet, there is no question that fostering industrialisation is high on the list of priorities for policymakers in Africa.

The reasons for the emphasis on industrialisation in Africa are clear. Historically, industrialisation has been associated with job creation, poverty reduction, and rapid growth in poor countries. There is no better example of this than China, where formal-sector manufacturing employed around 50 million workers in 2014 (Lardy 2015).1 A country like Ethiopia could employ its entire labour force with 50 million jobs.

But perhaps more importantly, the countries of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are rich in natural resources. African people are tired of sending raw materials to rich countries to be processed; they want to process these resources on their own turf to the benefit of their own people.

So, how much progress has been made toward industrialisation in SSA? Prior to the pandemic, countries in SSA had already achieved some success. Ethiopia has established an export-oriented garment and footwear sector with help from foreign investors. Tanzania has built a more resource-intensive manufacturing sector focused on serving domestic and regional markets. And Aliko Dangote, Africa’s wealthiest individual and a Nigerian businessman, is investing in oil refining, food processing, and cement manufacturing across the continent.

Recent research suggests that the premature de-industrialisation to which the continent had been subject may have been halted or even reversed after the early 2000s (Kruse et al. 2021) – though, as it turns out, even the authors of this somewhat upbeat picture of industrialisation in Africa point out that the ‘re-industrialisation’ they document is the result of employment growth in small unregistered manufacturing firms. In our work (Diao et al. 2021), we dig more deeply into the performance of the manufacturing sectors of Ethiopia and Tanzania using firm-level data.

Macroeconomic evidence

In our latest paper (Diao et al. 2021), we use the Groningen Growth and Development Center’s (GGDC) Economic Transformation Database to confirm a negative correlation between growth-promoting economy-wide structural change and labour-productivity growth within non-agricultural sectors in 18 African countries. This pattern also holds for the manufacturing sector, where labour productivity has been falling and labour-productivity growth has been either close to zero or negative. This result is consistent with the evidence presented in Timmer et al. (2015) and is surprising in so much as we are used to thinking of manufacturing as the canonical modern sector.

Based on statistics from the GGDC and UNIDO’s Industrial Statistics Database 2, we explore the hypothesis that this downward trend in labour productivity in manufacturing might have something to do with the composition of firms in the manufacturing sector.

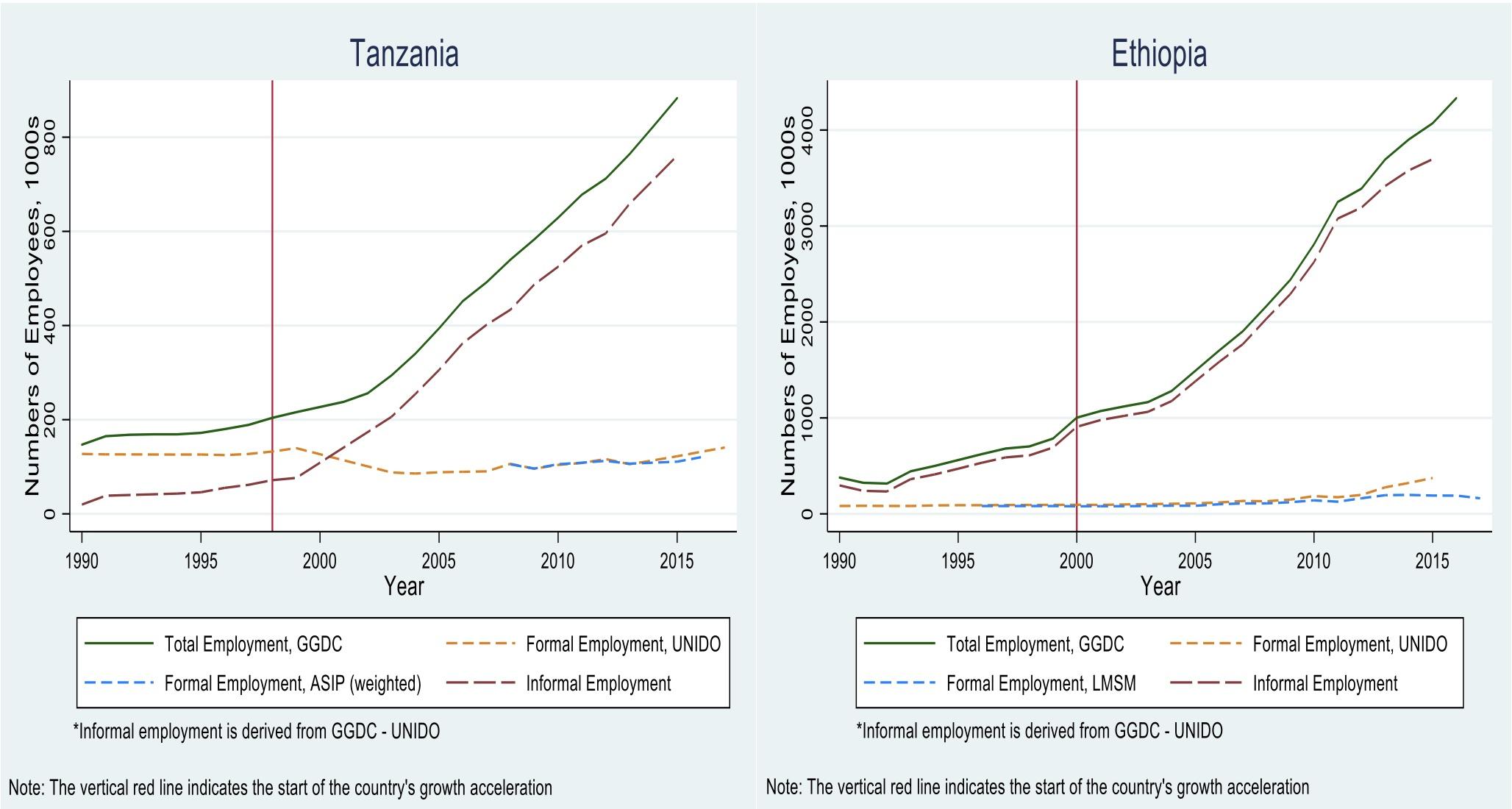

In Figures 1 and 2, we compare manufacturing employment trajectories across four countries: Ethiopia and Tanzania, and Taiwan and Vietnam. We plot three series: (i) total employment reported in the Economic Transformation Database; (ii) formal-sector employment, captured by the UNIDO statistics; and (iii) informal-sector employment, which we compute as total employment (Economic Transformation Database) minus formal-sector employment (UNIDO).

These trajectories are shown in the figures; the vertical line in each figure represents the start of a period of sustained growth in output per worker, as described in Diao et al. (2019).

Figure 1 Formal, small, informal, and total manufacturing employment in Tanzania and Ethiopia

Figure 2 Formal, small, informal, and total manufacturing employment in Taiwan and Vietnam

Notes: Total manufacturing employment comes from the GGDC 10 sector database. Formal sector employment is based on UNIDO data and in the cases of Tanzania and Ethiopia, we also plot formal sector employment using aggregates from the firm-level censuses for each country; these firms employ 10 or more workers. We label the difference between total and formal as small and informal firm employment. The vertical line represents the start of a period of sustained growth in output per worker, as described in Diao et al. (2019).

The contrast between the Asian and African countries is stark. The share of formal-sector manufacturing employment took off during the growth accelerations in Taiwan and Vietnam. In Tanzania and Ethiopia, it is the share of employment in small and informal firms that has expanded during the period of growth acceleration.2 To understand whether this pattern is responsible for declining labour productivity in Tanzanian and Ethiopian manufacturing, we turn to firm-level data.

Firm-level evidence

Our analysis rests on two newly created panels of manufacturing firms, one for Tanzania covering 2008-2016 and one for Ethiopia covering 1996-2017. In both cases, the panel covers firms with ten employees or more. But in the case of Ethiopia, we can supplement our analysis with nationally representative surveys of small-scale manufacturing firms employing fewer than ten workers, which are available for 2002, 2006, 2008, 2011, and 2014. With these data, we can take a finer-grained look at employment and productivity patterns within manufacturing firms and sub-sectors.

Our findings shed light on the nature and sources of manufacturing performance. In both countries, there is a sharp dichotomy between larger firms that exhibit superior productivity performance but do not expand employment much, and small firms that absorb employment but do not experience any productivity growth. The problem lies not in the productivity performance of the larger firms, which is more than adequate, but in their inability to generate employment opportunities. The labour-absorbing firms, by contrast, are the smaller ones that appear to be on significantly worse productive trajectories.

An interpretation: Inappropriate technology

Standard explanations for the lack of employment growth in the most productive manufacturing firms appear to be inadequate. First, the size distribution of firms in both countries, combined with the fact that smaller firms are considerably less productive than large firms, casts doubt on the idea that financing and other constraints prevent small firms from growing into large firms that would employ more workers (Hsieh and Olken 2014).

Second, high labour costs in Africa are sometimes cited as a constraint on industrialisation (Gelb et al. 2020). But we find that the payroll share in total value added in both Tanzania and Ethiopia is exceedingly low overall (11–12%) and also in garments and textiles (20–24%).3

Third, explanations based on the poor business environment in Africa are at odds with the dynamism in both countries’ manufacturing sectors captured in our analysis of entry and exit. In fact, entry and exit patterns in Tanzania and Ethiopia are not too dissimilar from those in Vietnam.

Instead, we suggest the problem might lie with the nature of technologies available to African firms. The relatively large firms in the Tanzanian and Ethiopian manufacturing sectors are significantly more capital intensive than what would be expected based on the countries’ income levels or relative factor endowments. This is especially true of the larger, most-productive firms, where capital intensity approaches (or exceeds) levels observed in the Czech Republic, a country that is around twenty-times richer. High levels of capital intensity (and possibly of skill intensity as well, although we do not measure that) are an important reason behind the poor employment performance of productive firms.

Why do firms in Tanzania and Ethiopia use production techniques that may not be particularly appropriate to the local economy? It is possible that they do not have much choice. Two things have happened in recent decades that push firms in that direction. First, manufacturing has experienced significant technological change in advanced economies. Naturally, innovation has taken a direction that responds to relative factor prices in the settings where it has taken place. So, it has been markedly labour-saving.

Secondly, globalisation and the spread of global value chains has had a homogenising effect on technology adoption around the world. This means that the range of substitution between capital and low-skill labour has likely shrunk. The imperative of competing with production in much richer countries at similar quality levels makes it difficult to undertake large shifts in technique.

Unlike earlier waves of developing nations, Tanzania and Ethiopia joined the world economy at a point where these two trends were already well established. Meanwhile, they are still poor and have very low relative capital endowments. This creates a conundrum: competing with established producers on world markets is only possible by adopting technologies that make it virtually impossible for significant amounts of employment to be generated.

The way forward

This is not to say that manufacturing cannot play an important role in the development of these countries. After all, productivity growth in the large manufacturing firms in Tanzania and Ethiopia has been impressive and could create jobs indirectly. For example, while the manufacturing of food products is capital intensive, smallholder farming is labour intensive. Worker training programmes associated with industrialisation strategies like Ethiopia’s Technical and Vocational Education and Training School could also enhance the capabilities of smaller firms. And the managerial and logistical capabilities of large manufacturing firms could be transferred to other activities through worker turnover or informal networks (Abebe et al. 2018). But tempering expectations is important, especially in politically fragile countries like Ethiopia.

References

Abebe, G, M S McMillan and M Serafinelli (2018), “Foreign direct investment and knowledge diffusion in poor locations: Evidence from Ethiopia”, NBER Working Paper 24461.

Diao, X, M McMillan D Dani Rodrik (2019), “The recent growth boom in developing economies: A structural-change perspective”, in The Palgrave Handbook of Development Economics, Palgrave Macmillan, 281–334.

Diao, X, M Ellis, M McMillan, and D Rodrik (2021), “Africa’s manufacturing puzzle: Evidence from Tanzanian and Ethiopian firms”, NBER Working Paper 28344.

Gelb, A, V Ramachandran, C J Meyer, D Wadhwa and K Navis (2020), “Can Sub-Saharan Africa be a manufacturing destination? Labor costs, price levels, and the role of industrial policy”, Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 20: 335–57.

Gollin, D (2018), “Structural transformation and growth without industrialisation”, Pathways for Prosperity Commission Background Paper no.2.

Hsieh, C-T and B A Olken (2014), “The missing ‘missing middle’”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(3): 89–108.

Kruse, H, E Mensah, K Sen and G de Vries (2021), “A manufacturing renaissance? Industrialization trends in the developing world”, World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNU-WIDER) Working Paper 2012/28.

Lardy, N (2015), “Manufacturing employment in China”, China Economic Watch, Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), 21 December.

Naidoo, K and L Ndikumana (2020), “Unit labor costs and manufacturing sector performance in Africa”, University of Massachusetts Amherst Economics Department Working Paper No. 2020-10.

Oqubay, A (2018), “The structure and performance of the Ethiopian manufacturing sector”, in F Cheru, C Cramer and A Oqubay (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Ethiopian Economy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Timmer, M, G J de Vries and K De Vries (2015), “Patterns of structural change in developing countries”, in J Weiss and M Tribe (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Industry and Development, Routledge, 79–97.

Endnotes

1 See the PIIE blog here.

2 See also Oqubay (2018) on Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector. Oqubay notes that Ethiopian manufacturing (until 2016-17) had played a marginal role in employment creation, exports, and output, and fell short in stimulating domestic linkages. While Oqubay expresses some optimism about the future of the manufacturing sector, he acknowledges that its disappointing employment performance is likely to be due to a combination of high capital intensity of firms, intense pressure to increase productivity, and the shrinking of public sector enterprises.

3 See Naidoo and Ndikumana (2020) for more recent evidence on labour costs in African manufacturing.