After accession to a customs union, Vinerian customs union theory suggests that trade diversion will reduce trade with third countries (Viner 1950). This happened to Australia's trade with the UK after Britain joined the European customs union in 1973. Australian agricultural exporters lost UK markets, and UK exporters focused their attention on Europe.

In 2004, the EU expanded to include ten new members, all with small economic links with Australia. A negative impact on third country trade was predicted (Pelkmans and Casey 2003, Fuller et al. 2002), although the impacts were not expected to be large.

Unexpectedly, Australia has increased its trade with – and especially its imports from – the new EU members. The four largest new members experienced growth in exports to Australia from 2005 to 2015 that was above the EU average, according to COMTRADE. Australian imports from Poland increased by 110% in 2005-15. In 2015 they were US$573 million, exceeded only by the original EU members, the UK, Ireland and Spain. Imports from the Czech Republic were $630 million, with growth in 2005-15 of 343%. For Hungary the figures are $409 million and 155%, and for Slovakia $344 million and 1,645%. (The Australian government data cited in Table 1 are slightly different, but the patterns are similar.)

The upturn in their imports from Australia was less striking (largest for Poland, minimal for Hungary and Slovakia), but there was no net diversion of their imports away from Australia. This could be explained if the acceding country’s pre-union tariff was reduced by adopting the EU common external tariff, but the acceding countries had already liberalised their international trade and joined the WTO before becoming EU members. More plausibly, accession-induced growth may have increased import demand in the acceding country. Campos et al. (2014) provide macroeconomic evidence that the Central and Eastern European economies as a group enjoyed faster growth, although it is not clear what the transmission mechanism was.

Regional value chains in Europe

The most plausible explanation of the export growth is that when new members join regional value chains (RVCs) within a customs union, this increases the member’s competitiveness in external markets.

When the EU Single Market was completed in 1986-92, it stimulated outsourcing. Egger and Egger (2003) connect the decrease of trade barriers in Eastern Europe after the fall of Communism in 1989 to outsourcing activities by Austrian firms. Aggregated input-output analysis shows that value-added in EU trade flattened in 1985-95, and then declined in 1995-2005 (Johnson and Noguera 2012). This reduction in value-added in trade is the counterpart to increased trade in parts and components, expanding RVCs. The EU phenomenon of RVCs has been highlighted by Marin (2006), di Mauro and Forster (2008), and Timmer et al. (2013), and these data suggest that the RVC phenomenon picked up in Europe during the second half of the 1990s.

Note this does not include trade in services (Egger et al. 2013), although this is clearly an important component of RVC trade. Also, using gross sales rather than trade in value-added would underestimate the role of the high-income EU countries in international trade.

After the end of Communism in 1989, many of the existing industrial enterprises in Central and Eastern Europe proved uncompetitive. They experienced deindustrialisation. Reindustrialisation in the 2000s was often characterised by outsourcing with considerable cross-country variation (Gurgul and Lach 2014). Pomfret and Sourdin (2014) document a large increase in the share of parts and components in Eastern European country trade between 2002 and 2012. Eastern European exports of parts and components were US$58 billion in 2002, $156 billion in 2007 and $195 billion in 2012. Imports were $67 billion in 2002, $184 billion in 2007 and $229 billion in 2012. The leaders in 2012 were the Czech Republic ($85 billion), Poland ($69 billion), Hungary ($53 billion) and Slovakia ($35 billion).

Australia and the 2004 EU members

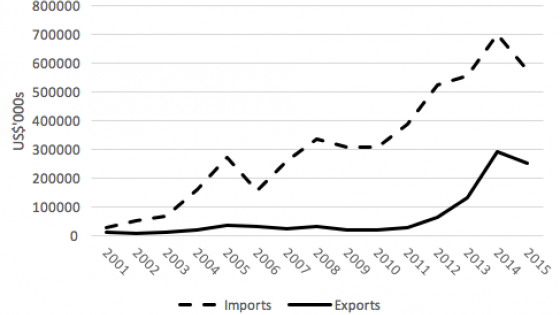

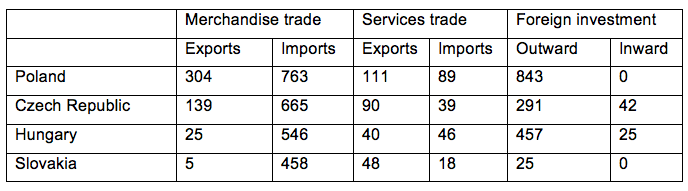

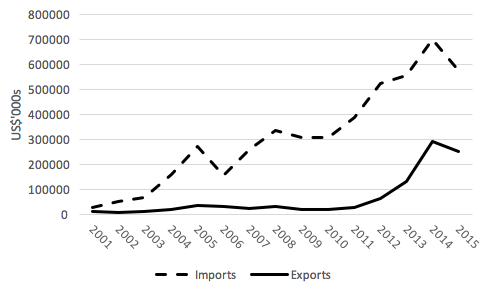

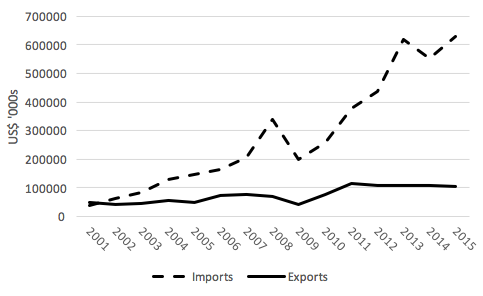

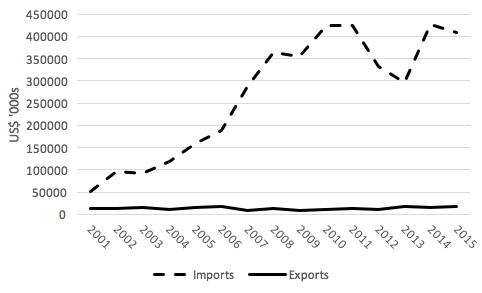

Since 2004, the four largest countries' trade with Australia has increased rapidly, especially since 2010. This overwhelmingly consisted of increased exports from the Eastern European countries to Australia. Australian exports consisted mainly of raw materials (for example $168 million coal and $44 million copper to Poland, or $122 million wool to the Czech Republic). Australian investment and services exports were centred on large infrastructure projects.

Table 1 Australian trade and investment with four European countries, 2015 (in millions of Australian dollars)

Source: Australia Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade website.

In Table 1 we are struck by Australia's large deficit in merchandise trade. This has largely emerged since 2010, as illustrated in the figures below. Moreover, the European countries' exports are heavily concentrated in a single product: passenger motor vehicles. In 2015, car exports to Australia from Poland were A$60 million, from the Czech Republic $269 million, from Hungary $179 million and from Slovakia $373 million. This is more than a third of all merchandise exports from the four countries to Australia and over four-fifths of Slovak exports to Australia.

Figure 1 Australia’s merchandise trade with Poland

Figure 2 Australia’s merchandise trade with Czech Republic

Figure 3 Australia’s merchandise trade with Hungary

Figure 4 Australia’s merchandise trade with Slovak Republic

Under central planning, Poland had a partnership with Fiat, Czechoslovakia had the largest indigenous car production with Škoda and Tatra, and Hungary – which had a large automotive components sector, but no car assembly plant - specialised in bus production. There was foreign investment in the 1990s, such as Volkswagen's purchase of Škoda in 1991, and investment in Hungary by Opel and Suzuki in 1991 and Audi in 1993, but expansion was slow and uneven in the 1990s. Opel abandoned car assembly in Hungary in 1996, and Tatra's car factory in the Czech Republic closed in 1998. Poland imposed the highest tariffs and import quotas for cars, encouraging Fiat to expand production and Opel to open a greenfield plant in 1998. Then, as restrictions on trade were lifted in 2001 in anticipation of EU accession, output fell.

Accession to the EU in 2004 and to the Schengen Area in 2007 reduced intra-EU trade costs for the Eastern European countries and provided a catalyst for development of RVCs, especially in the car industry. Creation of RVCs increased the competitiveness and export sales of EU cars, including those with final assembly in Eastern Europe that were exported to Australia. In the decade after 2004, the automobile RVC phenomenon has varied in intensity – it has been weakest in Poland, which was slow to shift from import substitution to an RVC mentality; it was essentially a one-brand show in Hungary; stronger and more diversified in the Czech Republic; and it was most dramatic in Slovakia.

All the greenfield investments after 2000 were in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, and when these factories reached capacity, the two countries had the highest per-capita car output in the world. In the Czech Republic, the TPCA factory started production of small Toyota, Peugeot and Citroen cars in February 2005 and reached the planned capacity of 300,000 cars in 2006. Hyundai started production in November 2008 with a capacity of 200,000 cars a year. In Slovakia, Volkswagen has been present since 1991, but output grew slowly until the company undertook further investment after 1998. PSA Peugeot Citroën have invested in Slovakia since 2003 and Kia has been investing since 2004. By 2006 the three factories had a capacity of over a million cars (PSA 450,000, VW 300,000 and Kia 300,000), the largest in Eastern Europe (Jakubiak et al. 2008), all with state-of-the-art technology. A contributory factor to the rapid expansion of Slovakia's car industry may be that Slovakia has been the only one of these four countries to adopt the euro, removing exchange rate uncertainty in RVC trade with Germany, France and other Eurozone countries.

Besides augmenting a country's attractiveness as an RVC participant, the common currency may be the driver of increased trade with third countries by making it easier for third-country exporters and importers to finance trade, especially with smaller countries adopting the euro (Rose and van Wincoop 2001).

In Hungary, Audi has expanded its facilities, and in it 2013 opened a new production plant for the Audi A3 Cabriolet and Limousine and TT Coupé and Roadster. Sales in 2013 were €5.6 billion (Bisztray 2016). Mercedes-Benz picked Hungary as its first plant in Eastern Europe, opening a factory in 2013. Suzuki produces several models, but is only one-third the size of Audi's Hungarian operation.

Although Poland's car exports to Australia have lagged behind those of the other three countries, the situation may be changing. GM Gliwice has been producing Holden Astras and Cascadas since February 2015, and the two millionth GM Gliwice car, produced in April 2015, was a Holden Cascada convertible for the Australian market. The Cascada was developed at Opel's International Technical Development Center in Rüsselsheim, Germany, assembled at GM's Polish plant in Gliwice, and marketed under Opel, Buick and Holden marques. Fiat Chrysler had previously reduced the number of models assembled in Poland, and a major activity from 2008-16 was production of the Ford Ka under licence. It has revived production with new models of the Fiat 500 and Lancia Ypsilon in 2015, and appeared to be looking to export markets when the company announced in September 2015 a $100 billion investment in the Tychy plant.

As the four countries became integrated in car and other RVCs, their trade within the EU and with third countries flourished. Reductions in the trade costs of the four East European countries have made it easier to export to Australia. In 1990, apart from Hungary, the countries' costs of trading with Australia were higher than the average trade costs of imports into Australia, and much higher than the trade costs of Germany (Table 2). After 2005 these trade costs were reduced and for Hungary and Slovakia. They are equal to or below Germany's trade costs, despite both countries being landlocked.

Table 2 Trade costs on exports to Australia (ad valorem)

Notes: (cif-fob)/fob, adjusted for commodity composition - calculated from Australian Bureau of Statistics data, as described in Pomfret and Sourdin (2011).

RVCs increased trade with Australia

In stark contrast to its experience after the 1973 enlargement, after the 2004 EU enlargement Australia's trade with new members increased dramatically. The principal driver has been the integration of the four largest new members into EU regional value chains, and this process has been clearest in the car industry. Trade with Australia has also been facilitated by a large drop in the costs of bilateral international trade, most dramatically in the case of Slovakia. This is likely related to factors that enhanced Slovakia's attractiveness as an RVC participant, such as improved ease of doing business and of crossing borders, including adoption of the euro and accepting Schengen status.

Authors’ note: The research was supported by a grant from the EU Centre for Global Affairs at the University of Adelaide. The project is reported in the University of Adelaide School of Economics Working Paper "Trade between Australia and the EU, 1990-2015".

References

Bisztray, M. (2016), “The Effect of FDI on Local Suppliers: Evidence from Audi in Hungary”, Discussion Paper MT-DP–2016/22, Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest.

Campos, N., F. Coricelli and L. Moretti (2014), “Economic Growth and Political Integration: Estimating the Benefits from Membership in the European Union Using the Synthetic Counterfactuals Method”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 8162 (see also the Vox column at http://www.voxeu.org/article/how-poorer-nations-benefit-eu-membership).

Di Mauro, F, and K. Forster (2008), “Globalisation and the Competitiveness of the Euro Area”, ECB Occasional Paper No. 97

Egger, H., and P. Egger (2003), “Outsourcing and Skill-specific Employment in a Small Economy: Austria after the fall of the Iron Curtain”, Oxford Economic Papers 55(4), 625-43.

Egger, P., M. Larch and K. Staub (2012), “Trade Preferences and Bilateral Trade in Goods and Services: A Structural Approach”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9051.

Fuller, F., J. C. Beghin, J. Fabiosa, S. Mohanty, C. Fang, and P. Kaus (2002), “Accession of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland to the European Union: Impacts on agricultural markets”, The World Economy 25, 407-428.

Gurgul, H, and L. Lach (2016), “Comparative Advantages of the EU in Global Value Chains: How important and efficient are new EU members in transition?”, Managerial Economics 17(1), 21-58.

Jakubiak, M., P. Kolesar, I. Izvorski, and L. Kureková (2008), “The Automotive Industry in the Slovak Republic: Recent developments and impact on growth”, The Commission on Growth and Development Working Paper No.29 (World Bank, Washington DC).

Johnson, R., and G. Noguera (2012), “Proximity and Production Fragmentation”, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 102(3), 407-11.

Marin, D. (2006), “A New International Division of Labor in Europe: Outsourcing and Offshoring in Eastern Europe”, Journal of the European Economic Association 4, 612-22.

Pelkmans, J., and J-P. Casey (2003), “EU Enlargement: External Economic Implications”, Intereconomics 38(4), 196-208.

Pomfret, R., and P. Sourdin (2011), “Why do Trade Costs Vary?”, Review of World Economics (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv) 146(4), 709 -30.

Pomfret, R., and P. Sourdin (2014), “Global Value-Chains and Connectivity in Developing Asia – with application to the Central and West Asian region”, ADB Working Paper Series on Regional Economic Integration No.142, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

Rose, A., and E. van Wincoop (2001), “National Money as a Barrier to Trade: The real case for monetary union”, American Economic Review 91(2), 386-90.

Timmer, M., B. Los, R. Stehrer and G. de Vries (2013), “Fragmentation, Incomes, and Jobs: An Analysis of European Competitiveness”, Economic Policy 28(76), 613-61.

Viner, J. (1950), The Customs Union Issue, New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.