Over the last decade, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have become more widespread and their performance has improved. Policymakers, scholars, and advocates have raised concerns of algorithmic bias, data privacy, and transparency, which issues have gained increasing attention, and renewed calls for policy to address the consequences of technological change (Frank et al. 2019).

As AI continues to improve and diffuse, it will likely have important long-term consequences for jobs, inequality, organisations, and competition. These developments may spur interest in regulation as a potential means to address the risks and possibilities of AI. Yet, very little is known about how different kinds of AI-related regulation – or even the prospect of regulation – might affect firm behaviour.

AI is already being implicitly regulated through common law doctrines such as tort and contract law, as well as through statutory and regulatory obligations on organisations such as emerging standards governing autonomous vehicles (Cuéllar 2019).

As AI technologies are diffusing rapidly and have wide-ranging social and economic consequences, policymakers and federal and state agencies are contemplating new ways of regulating AI. These include broad proposals of general AI regulation such as the Algorithmic Accountability Act in the US, which was introduced in the House of Representatives on 10 April 2019. State regulations include the California Consumer Privacy Act, which goes into effect from January 2020. Domain-specific regulations in the US are also currently being developed by federal regulators such as the Food and Drug Administration, the National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration, and the Federal Trade Commission.

The randomised online survey experiment

In a recent paper, we examine the impact of these actual and potential AI regulations on business managers (Lee et al. 2019). In particular, we assess how likely managers are to adopt AI technologies and alter their AI-related business strategies as they are asked to reflect on the regulation of AI.

We conduct a randomised online survey experiment where the treatment group is informed of the core features of different regulatory treatments. Specifically, we randomly expose managers to one of the following treatments:

- a general AI regulation treatment that invokes the Algorithmic Accountability Act;

- industry-specific regulation treatments that invoke the relevant agencies, i.e. the Food and Drug Administration (for healthcare, pharmaceutical, and biotech), National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration (for automobile, transportation, and distribution), and the Federal Trade Commission (for retail and wholesale);

- a treatment that reminds managers that AI adoption in businesses are subject to existing common law and statutory requirements such as tort law, labour law, and civil rights law; and

- a data privacy regulation treatment that invokes the California Consumer Privacy Act.

We study how these varying regulations affect managers’ decision-making, and how managers revise their business strategies when faced with new regulation.

Key findings

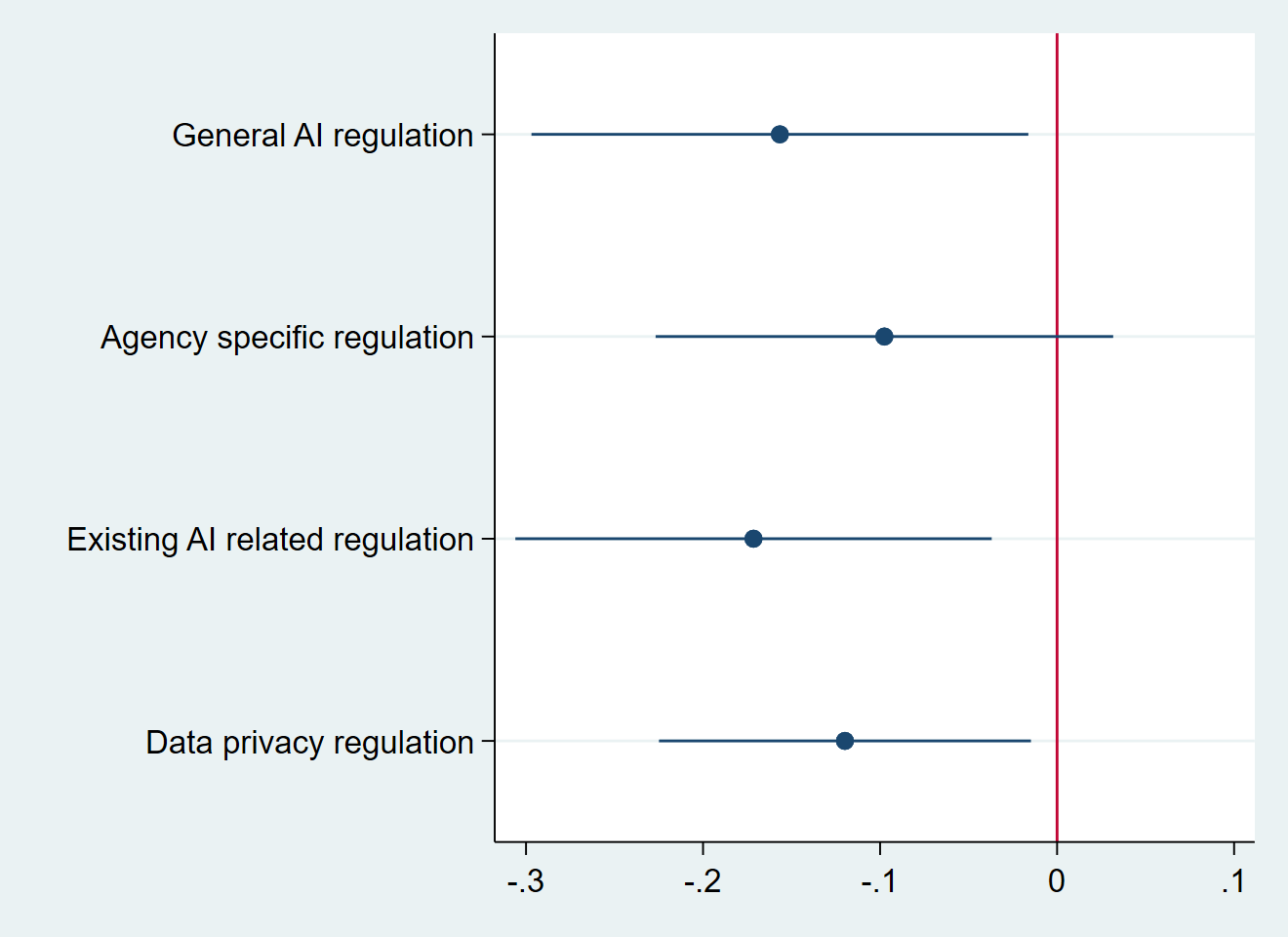

Our results indicate that exposure to information about regulation decreases managers’ reported intent to adopt AI technologies in the firm’s business processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Coefficient plot of the treatment effects of AI regulation on adoption

Notes: The dots represent the coefficient estimates from the regression and the bar represents the 95% confidence interval. Each coefficient estimate represents the difference between each treatment group and the control group.

We find that exposure to information about general AI regulation, such as the Algorithmic Accountability Act, reduces the reported number of business processes in which managers are reportedly willing to use AI by about 16%. We also find that exposure to information about AI regulation significantly increases expenditure on developing AI strategy (Figure 2).

This impact is strongest for the ‘general AI regulation’ treatment, which increases allocation to AI strategy purposes by three percentage points. The increase in budget for developing AI business strategy is primarily offset by a decrease in the budget for training current employees on how to code and use AI technology and purchasing AI packages from external vendors.

Figure 2 Coefficient plots of the treatment effects of AI regulation on budget allocation

Notes: The dots represent the coefficient estimates from the regression and the bar represents the 95% confidence interval. Each coefficient estimate represents the difference between each treatment group and the control group.

In addition, exposure to information about AI regulation significantly increases the intent to hire more managers (Figure 3). In other words, making the prospect of AI regulation more salient seems to force firms to ‘think’, inducing firms to report greater willingness to expend more on strategising but at the cost of developing internal human capital.

Figure 3 Coefficient plots of the treatment effects of AI regulation on adjustment to labour

Notes: The dots represent the coefficient estimates from the regression and the bar represents the 95% confidence interval. Each coefficient estimate represents the difference between each treatment group and the control group.

Exposure to information about AI regulation also increases how important managers consider various ethical issues when adopting AI in their business (Figure 4). Each regulation treatment increases the importance managers put on safety and accident concerns related to AI technologies. In particular, the ‘existing AI regulation and data privacy regulation’ treatment significantly increases manager perceptions of the importance of privacy and data security. The agency-specific regulation also increases manager perceptions of the importance of bias and discrimination, and transparency and explainability.

Figure 4 Coefficient plots of the treatment effects of AI regulation on importance of ethical issues

Notes: The dots represent the coefficient estimates from the regression and the bar represents the 95% confidence interval. Each coefficient estimate represents the difference between each treatment group and the control group.

Heterogeneous effects by industry and firm size

We find significant heterogeneity in the effects of AI-regulation information by industry and firm size. Regulation decreases AI adoption in the healthcare and retail sectors but not the transportation sector. Moreover, it is primarily in the transportation sector that AI regulation results in higher budget allocation to developing AI strategies.

In terms of innovation activities, we find that AI regulation increases firms’ intent to file patents in the healthcare sector but decreases it in the retail and wholesale sector. This is likely due to patents being a vital part of the healthcare industry (i.e. drug discovery), while the core business in retail is far less dependent on patents as a primary strategy for operation.

The negative impact of AI-regulation information on AI adoption is more significant for small firms, which we define as those with revenue less than $10 million. Also, these small firms are the ones that increase their budget allocation to AI-strategy development and hire more managers in response to new regulations. However, large firms respond to the ‘existing AI regulation’ treatment, which invokes the relevance of tort law and civil rights protections. Managers of large firms exposed to this treatment increase their awareness of ethical issues, increase the budget share for developing AI strategies, and plan to hire more managers.

These results highlight the potential trade-offs between regulation and the diffusion and innovation of AI technologies in firms and signal important implications for regulators and policymakers.

Key implications for AI regulation

Our findings suggest several potential implications for the design and analysis of AI-related regulation. First, where possible, regulators should adapt regulations to the needs and concerns arising in specific industries. Although policymakers sometimes find compelling rationales for adopting broad regulatory responses to major problems such as environmental protection and occupational safety, cross-cutting AI regulation such as the proposed Algorithmic Accountability Act may have enormously complex effects and make it harder to take potentially significant sector characteristics into account.

Second, policymakers will do a better job designing and communicating regulatory requirements if they retain a clear focus on regulatory goals. Given the impact of industry sector and firm size on responses, policymakers would do well to meticulously approach AI regulation across different technological and industry-specific use cases. While the importance of certain legal requirements and policy goals – such as reducing impermissible bias in algorithms and enhancing data privacy and security – may apply across sectors, specific sectoral features may nonetheless require distinctive responses. For example, the use of AI-related technologies in autonomous driving systems must be responsive to a diverse set of parameters that are likely to be different from those relevant to AI deployment in drug discovery or online advertising.

Third, given the level of concern among constituencies and target groups for regulation, policymakers should bear in mind the full range of regulatory tools available in the AI context. These include continued reliance on existing legal requirements with relevance to AI, such as tort law and employment discrimination, that can be gradually elaborated by courts or administrators. Policymakers should also consider the merits of soft-law governance of AI, as well as the costs and benefits of reliance on AI industry standards.

The question of what kinds of regulations are appropriate and most needed by society will remain intricate. No doubt further research to examine the potential impact of AI regulation will help regulators design appropriate AI regulatory frameworks and consider how to implement and adapt existing laws. As policymakers consider the trade-offs, our results underscore the extent to which business managers are sensitive to the risks and costs associated with AI regulation. Their responses can have profound effects on workers, businesses, and consumers in the years to come.

References

Cuéllar, M (2019), “A common law for the age of artificial intelligence: Incremental adjudication, institutions, and relational non-arbitrariness”, working paper.

Frank, M R, D Autor, J E Bessen, E Brynjolfsson, M Cebrian, D J Deming, et al. (2019), “Toward understanding the impact of artificial intelligence on labor”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(14): 6531–39.

Lee, Y S, B Larsen, M Webb, and M Cuéllar (2019), “How would AI regulation change firms’ behavior? Evidence from thousands of managers”, SIEPR Working Paper 19-031.