The shock of the pandemic spurred a large-scale experiment in remote working (Baldwin 2020). In doing so, it has loosened the binds that previously tied a job to a specific geography and created a new class of work in the UK in the form of ‘anywhere jobs’ – non-routine service-sector jobs that can be done fully remotely from anywhere in the world, most likely for cheaper (Kakkad et al. 2021).

In recent decades, it was typically semi-skilled manufacturing and clerical jobs that were vulnerable to automation and offshoring, while professional white-collar jobs thrived and were largely sheltered from the pressures of technological change.

But the pandemic changed this. It forced businesses of all sizes to accelerate their digital adoption (Riom and Valero 2020), allowing them to unbundle service-sector value chains; automate, outsource or offshore non-core activities (Weil 2017); and manage and monitor that work more closely (Gilbert and Thomas 2021).

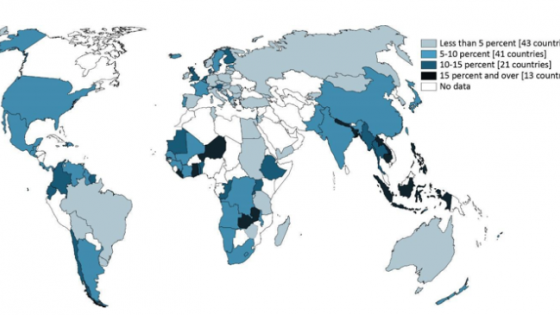

As a services-based economy, the UK has the highest potential for remote working in the G7 (Lund et al. 2020), leaving it exposed to any shifts in the relative demand for white-collar jobs. This potential transformation in workforces (Berg et al. 2020) could be as profound as that seen in manufacturing over the past 40 years but on an accelerated timeframe of the next 5-10 years.

Identifying anywhere jobs

The potential to work from anywhere will be determined by the tasks and activities inherent to a role. The Occupational Information Network (O*NET) data set contains information on the tasks and activities in over 800 occupations, which enables us to identify which jobs need to be carried out in person, and those with the greatest potential to be done fully remotely (i.e. an anywhere job).

What emerges through this analysis is a set of anywhere jobs with one or more of the following characteristics:

- Limited physical activity: Tasks that are typically non-routine, require a degree of technical, specialist, or creative knowledge, and are done digitally and not tied to a physical location.

- Asynchronous and detailed tasks: Tasks that require high attention to detail, yet rarely, if ever, need to be done in the same location or time zone as work in the rest of the business.

- Limited responsibility: Tasks that require infrequent decision-making and have limited direct commercial consequences, making the work relatively self-contained and peripheral to the core of the business.

Anywhere jobs are therefore distinct from the manufacturing and clerical roles with routine tasks that were automated or offshored. They are also a different class of jobs than typically discussed in the current debate on automation, which divides work into so-called ‘execution’ jobs that are at risk of automation and ‘exploration’ jobs that are relatively safe (Frey 2019).

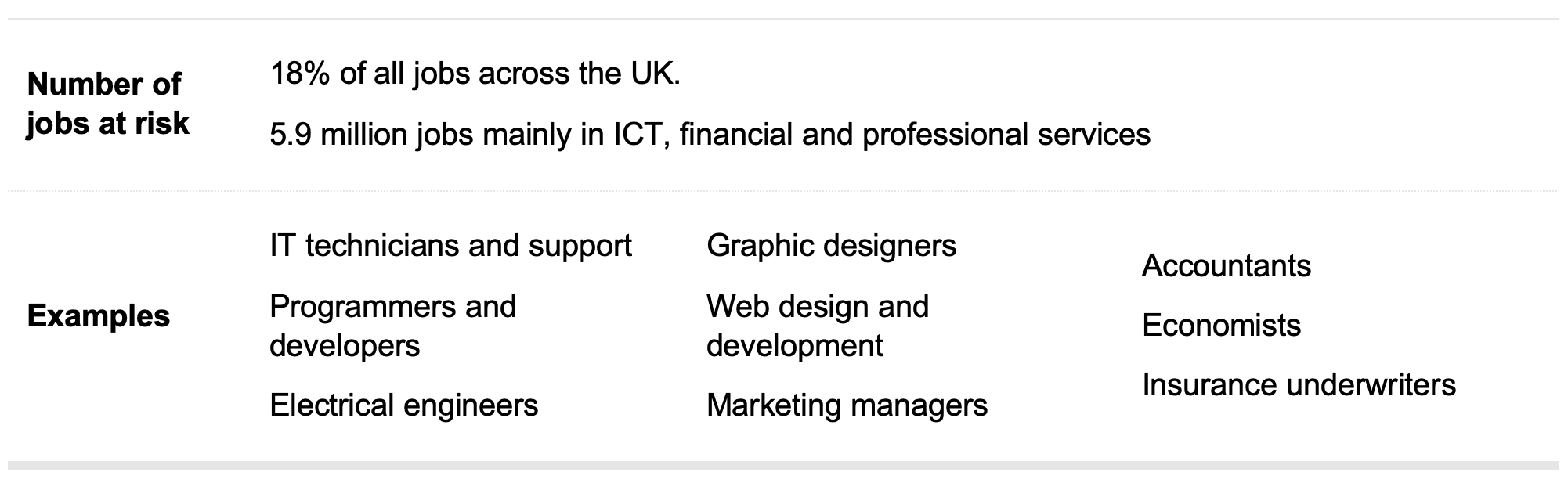

Overall, we find that 18% of jobs in the UK – 5.9 million in total – are anywhere jobs. Looking at the occupational breakdown, anywhere jobs are predominantly in professional (36%), technical (30%), and administrative (24%) occupations. Of all anywhere jobs, 1.7 million (28%) are in the finance, research, and real-estate sectors, and 1.1 million (18%) are in transport and communication. These are also the sectors most vulnerable when considering the percentage of their workforce at risk.

Table 1 Overview of anywhere jobs in the UK

There are also common occupations across the different industries: IT, human resources, legal secretaries, and personal assistants are among the most common anywhere jobs. There are also industry-specific occupations that most commonly have a creative, research, or technical element. In finance and professional services, they are financial and accounting technicians, and pensions and insurance clerks. In transport and telecommunications, anywhere jobs include programmers, software developers, and marketing professionals.

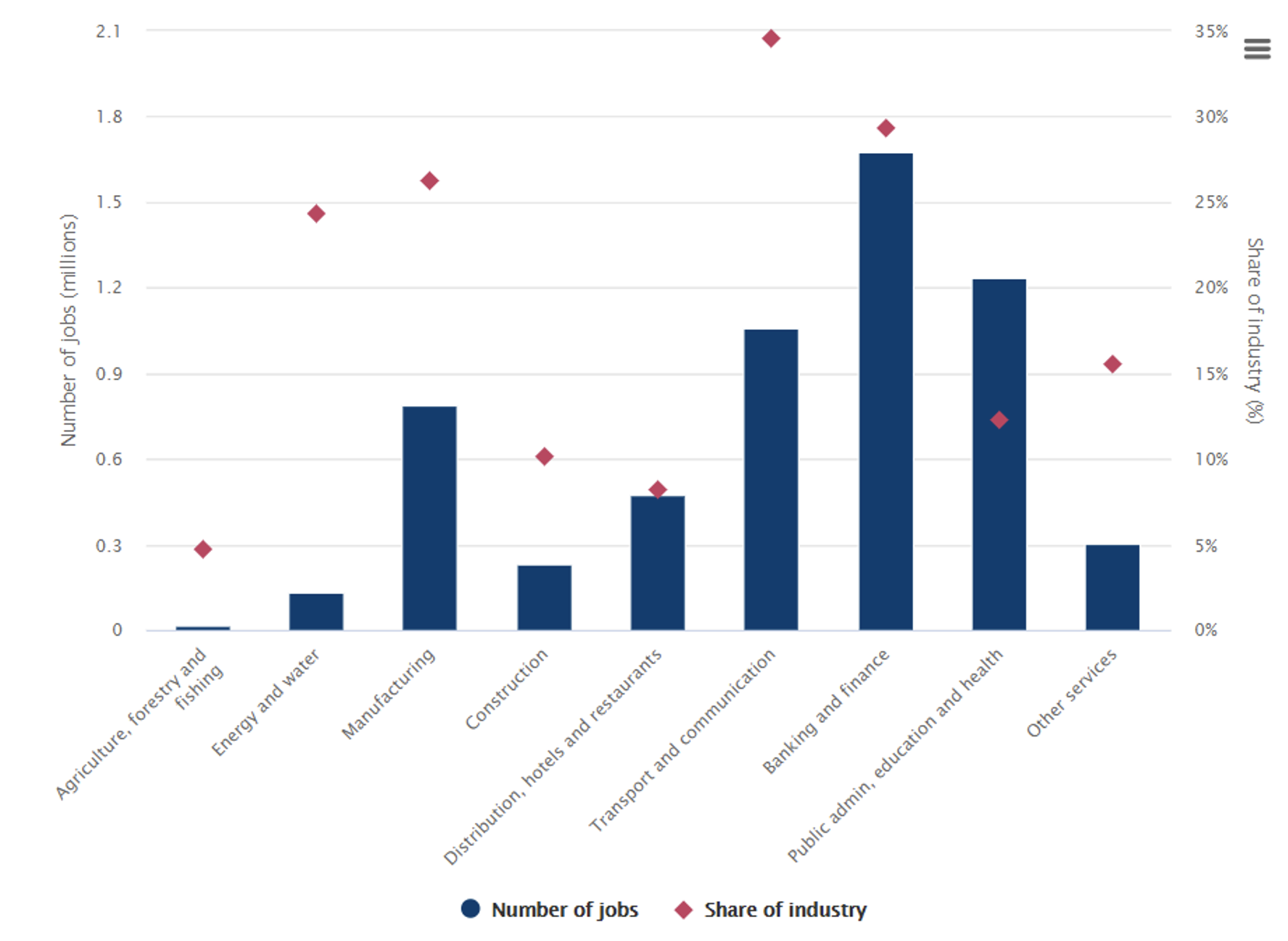

Figure 1 Most anywhere jobs in the UK are in the finance and professional services sectors

Source: TBI, O *NET and ONS

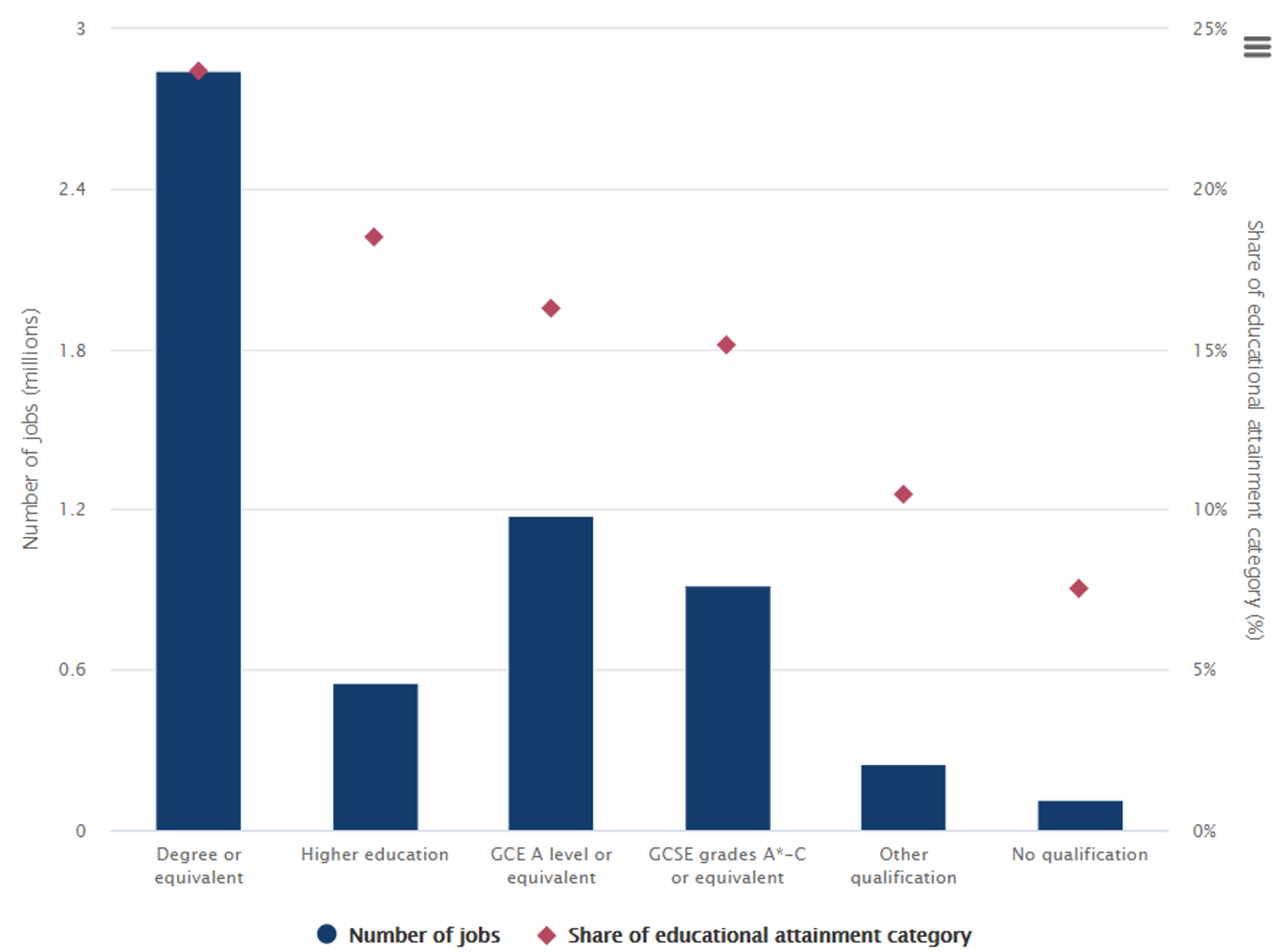

Overall, 48% (2.8 million) of those in anywhere jobs have a degree. Indeed, 20% of people educated to degree level or higher in the UK are working in an anywhere job. As opposed to the decades-long pressure on semi-skilled workers, the current technological transformation is putting highly-skilled workers in non-routine jobs at risk of being outsourced or offshored.

Figure 2 Anywhere jobs by qualification level

Source: TBI, O *NET and ONS

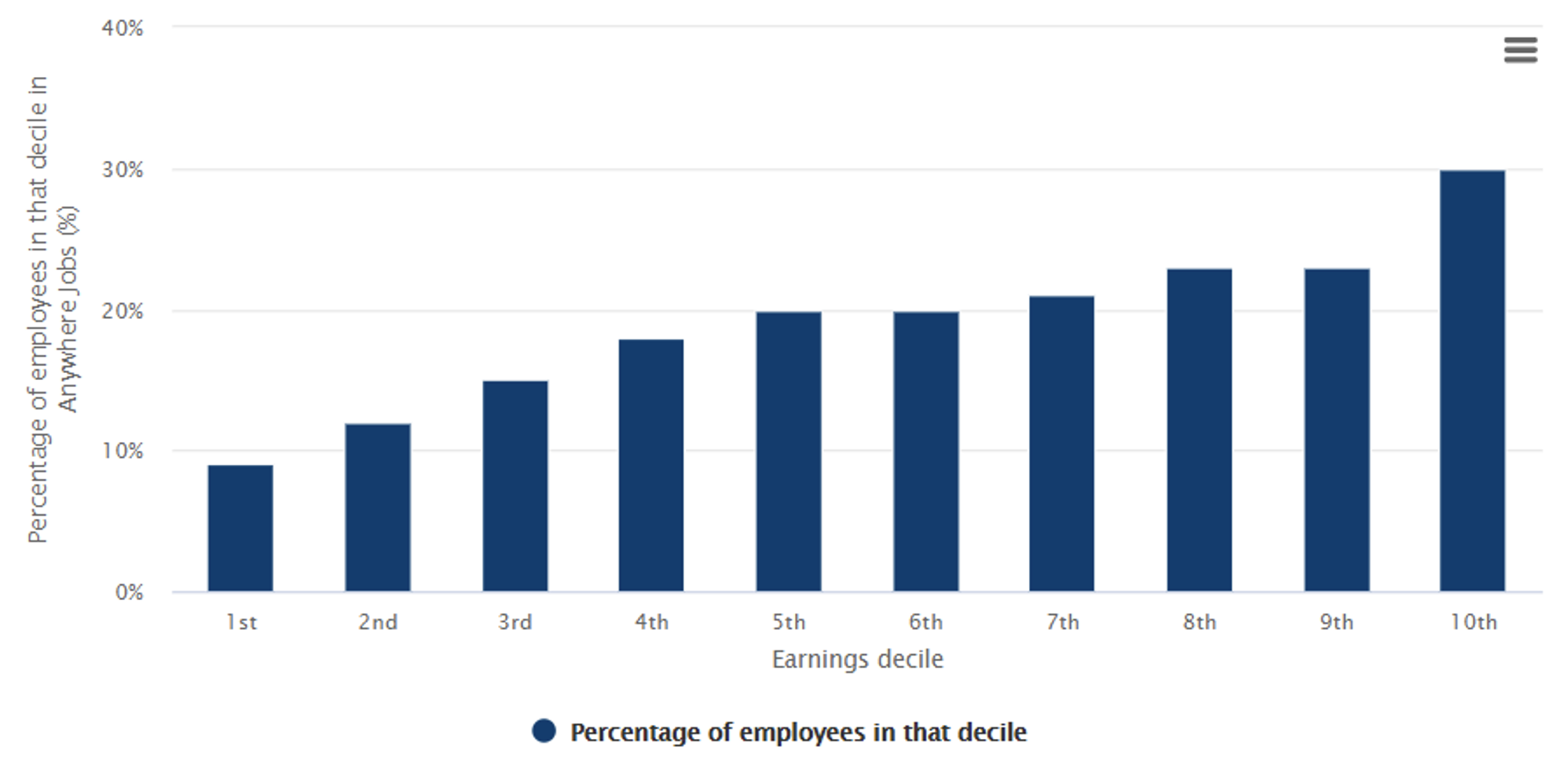

Looking by earnings decile, the share of anywhere jobs increases across the earnings distribution. If anywhere jobs are outsourced to digital piecework platforms or offshored to lower labour-cost economies, this competition could put pressure on earnings at the top end of the earnings distribution.

Figure 3 Anywhere jobs by earnings decile

Source: TBI, O*NET and ONS

Young professionals in the 25-34-year-old age group account for 1.6 million (27%) of anywhere jobs. They are relatively more vulnerable, with 21% of this group in an Anywhere Job. The likelihood of working in an anywhere job decreases by age. In addition, 2.3 million (39%) of those in anywhere jobs are parents with dependent children. Given the challenges younger workers faced before the pandemic in terms of workplace security, pay and progression (Gardiner et al. 2020), exposure to anywhere jobs is an additional risk that could contribute to widening intergenerational inequalities.

Not all anywhere jobs will move abroad

When businesses decide where to locate an investment, they consider a range of factors including political and economic stability, tax and subsidy regimes, and transport infrastructure (World Economic Forum 2019). For these decisions, there is no one-size-fits-all or hard-and-fast rules about what will determine the investment choice. The same will apply with anywhere jobs, except now social and cultural infrastructure could matter as much as physical infrastructure and regulatory systems.

Based on conversations with businesses and workers, the factors that are likely to determine whether an anywhere job stays in the UK or moves abroad include:

- Support systems and infrastructure: Workers need support systems that make remote working a realistic day-to-day option, such as cheap, available childcare and adequate housing, workspace, devices, and connectivity. For employers, what matters is the ability to navigate taxation, and employment and identification regimes for remote workers.

- Access to skills: For businesses, remote working means they can recruit from a wider geography and use digital platforms to reduce the search costs of finding global talent. In contrast, easy access to a broad and deep pool of talent could help make the UK an attractive destination to place anywhere jobs, whether the company is in the UK or abroad.

- Productivity and wellbeing: As companies consider the return to the office, they are looking at how to cut costs and boost productivity. Some may decide to make employment costs more variable through outsourcing anywhere jobs, while others rethink their management practices to enhance wellbeing and foster collaboration.

- Connection to community: As shifts in technology and remote working change the geography of work, connections to communities, the strength of social capital, and shared culture, history, and language could also play roles in determining what happens to anywhere jobs.

- Competitive pressures: As companies restructure their operations following the pandemic, the pressures they face from either competitors or investors could also determine how they reshape their business models and, therefore, where Anywhere Jobs fit within that framework.

Reshaping the geography of jobs

International competition for remote workers has already started (Baldwin and Forslid 2020). Offshoring or outsourcing anywhere jobs is likely to introduce greater wage pressure on jobs further up the earnings distribution. Yet if they are shifted abroad, the UK could also see rising relative demand for the roles that are left – proximity services and non-cognitive, non-routine professional services – increasing polarisation and income inequality in the UK labour market (Wilmers and Aeppli 2021).

The UK does not have to be fatalistic about anywhere jobs; there is nothing inherent about them that means they will automatically be outsourced or offshored. On the contrary, there is a range of actions the government could take to not only help anchor anywhere jobs in the UK but equally attract remote workers here, including:

1. Strengthening the support infrastructure – such as childcare, transportation, 5G and gigabit broadband, and suitable housing and workspace – to make remote working a reality across the whole of the UK.

2. Designing new forms of skills and (re)training. While STEM skills are still valuable, the priority must be investing in the non-cognitive, social and digital skills that have seen – and are likely to continue to see – relatively higher levels of wage growth (Deming 2017).

3. Renewing the social contract to support more mobile, flexible workforces. Social insurance, worker representation, and taxation systems need to be redesigned to fit a more flexible world of work and to help people be resilient to risk and attain human capital.

Not all anywhere jobs will be outsourced or offshored. But the economic, social, and political legacy of accelerated deindustrialisation over the past 40 years shows that the UK must get ahead of this next wave of technological transformation to benefit economically.

References

Baldwin, R (2020), “Covid, hysteresis and the future of work”, VoxEU.org, 29 May.

Baldwin, R, and R Forslid (2020), “Covid 19, globotics, and development”, VoxEU.org, 16 July.

Berg, J, F Bonnet and S Soares (2020), “Working from home: Estimating the worldwide potential”, VoxEU.org, 11 May.

Deming, D (2017), “The growing importance of social skills in the labour market”, NBER Working Paper.

Frey, C B (2019), The technology trap: Capital, labor, and power in the age of automation, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gardiner, L, M Gustafsson, M Brewer, et al. (2020), “An intergenerational audit for the UK”, Resolution Foundation.

Gilbert, A, and A Thomas (2021), “The Amazonian Era: How algorithmic systems are eroding food work”, Institute for the Future of Work.

Kakkad, J, C Palmou, D Britto and J Browne (2021), “Anywhere jobs: Reshaping the geography of work”, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

Lund, S, A Madgavkar, J Mayika and S Smit (2020), “What’s next for remote work: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs and nine countries”, McKinsey and Company, 23 November.

Riom, C, and A Valero (2020), “The business response to Covid-19: The CEP-CBI survey on technology adoption”, LSE Centre for Economic Performance.

Weil, D (2017), The fissured workplace: Why work became so bad for so many and what can be done to improve it, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilmers, N, and C Aeppli (2021), “Consolidated advantage: New organizational dynamics of wage inequality”, Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

World Economic Forum (2019), “The global competitiveness report”.