We have learned much about the causes and consequences of financial crises following the 2008–2009 Great Recession (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009, 2011, Schularick and Taylor 2012). In particular, recent research has shown that deleveraging cycles seem to play an influential role in economic fluctuations (Jordà et al. 2013, Mian et al. 2017).

In this column we discuss our new research that argues that studying the response of international trade flows to crises can shed light on the nature of crises (Benguria and Taylor 2019). The key and simple insight behind our approach is that the demand and supply for goods traded internationally are set geographically apart, and thus hit by crises at different points in time. This allows us to tell apart the demand versus supply shock hypotheses with a transparent empirical strategy.

We interpret the empirical evidence through the lens of a simple small open economy model of deleveraging shocks to households and firms (i.e. demand and supply shocks). This model generalises Eggertson and Krugman’s (2012) framework to an open economy setting. We build the exact same structure of tightening borrowing constraints on the household and on the firm side, to compare the response of exports, imports, and the real exchange rate to both types of shocks. The behaviour of the economy in response to shocks to firms or households is very distinct. Firm deleveraging shocks contract exports, leave imports largely unchanged, and appreciate the real exchange rate. Household deleveraging shocks tend to contract imports, leave exports largely unchanged, and depreciate the real exchange rate.

The evidence comes from a new dataset that combines 200 years of financial crises dates, bilateral international trade flows, and bilateral real exchange rates among a broad panel of 69 countries. As large financial crises are rare events, looking at the historical record becomes essential to obtain a clear picture. We study 195 crisis episodes 77 in advanced countries and 118 in developing economies; 108 in the post-WWII period and 87 pre-WWII.

Figure 1 World trade and major crises

Note: This figure is constructed aggregating exports and GDP for a constant sample of the following 10 countries: Australia, Chile, Denmark, Spain, France, the UK, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, and the US. Vertical dashed lines indicate the starting year of four major world financial crises: the Panic of 1873, the 1930s Great Depression, the 1980s LDC sovereign-financial crises, and the 2008 Great Recession.

Whether financial crises are negative demand or supply shocks is one of macroeconomics’ perennial and fundamental questions. Beyond intellectual curiosity, views on this debate shape government policies in response to crises. Naturally, interest in this question spikes after major global downturns, from the Great Depression in the 1930s to the recent 2008-2009 global financial crisis. The fact that this debate lingers is perhaps a sign that clear empirical evidence able to discern between both views is still very necessary.

For the sake of motivation, we start by noting that what was witnessed after the global financial crisis in 2008 was nothing new, especially not the so-called Great Trade Collapse (i.e. the fall in trade volumes relative to GDP). Figure 1 shows the trajectory of world exports/GDP after four major global financial crises between 1827 and the present. Similar declines in world trade can be seen to have occurred after each of these crisis events. While this figure motivates our work, it hides the uneven impact of financial crises on imports and exports, and the correlation between those shocks and the location of the underlying financial frictions.

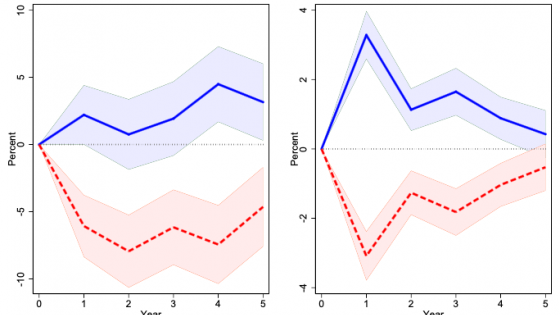

In our main econometric results, we examine the response of bilateral trade flows and bilateral real exchange rates to financial crises occurring in either the exporting or the importing country using local projection methods. Following a financial crisis event, we see statistical evidence strongly in favour of the demand-side view: on impact, imports contract, exports hold steady or even rise, and the real exchange rate depreciates. Figure 2 illustrates our main result.

Figure 2 Local projections: Response of bilateral trade and the real exchange rate (RER) to financial crisis in exporter or importer

Note: This figure shows the response of the level of bilateral GDP-normalized trade and the level of the bilateral real exchange rate to financial crisis in either exporter country e or importer country i. Shaded regions indicate 90% confidence intervals.

On impact, a financial crisis in the exporter country is associated with a 2.2% increase in trade (after normalising by GDP). A financial crisis in the importer country, in contrast, is associated with a 6.1% decrease in trade. These effects remain of a similar magnitude and are statistically significant even out to a five-year horizon. Regarding the effect on bilateral real exchange rates, a financial crisis in the exporter country is associated with a 3.3% appreciation in the real exchange rate on impact. A financial crisis in the importer country is associated with a 3.1% depreciation in the real exchange rate.

Comparing these results with our model, it becomes clear that these patterns are inconsistent with the supply-side view, but quite consistent with the demand-side view of financial crises.

We go beyond aggregating trade in all types of goods and further distinguish between trade in final goods and trade in intermediate inputs for the post-WWII period. In the model, a deleveraging shock to households reduces their demand for imported final goods as well as their demand for non-traded goods, which in turn causes firms to import fewer intermediate inputs. Firm deleveraging shocks, in contrast, limit production and imports of intermediate inputs fall, whereas imports of final goods are stable. Empirically, we find that financial crises depress imports of both final and intermediate goods. This, again, is consistent with the model’s predictions following a household deleveraging shock, providing further empirical evidence consistent with the demand-side view of crises.

In both theory and empirics, rather than studying only the effects on final goods, we further distinguish between trade in final goods and trade in intermediate inputs. In our model, household deleveraging shocks reduce the demand for imported final goods. In addition, households demand fewer non-traded goods, which causes firms to import fewer intermediate inputs. In the case of firm deleveraging shocks, which limit production, imports of intermediate inputs fall, whereas imports of final goods are largely stable. To explore this extension to the model empirically, we constructed data on trade flows by product type for the post-WWII period, and find that financial crises depress imports of both final and intermediate goods, providing further empirical evidence consistent with the demand-side view of crises.

Our empirical design allows for the possibility that financial crises are endogenous to macroeconomic conditions. Following Jordà et al. (2016), we use the method of inverse propensity-score weighting to address the problem of bias arising from selection on observables, using pre-crisis credit growth as a predictor of financial crises. The results are unaffected. The results are also robust to controlling for other types of crises, including currency and inflation crises, stock market crises, external and domestic sovereign debt crises, and sudden stop episodes.

Summing up, analysing the response of international trade flows and crises can be enlightening for our understanding of the nature of these events. The historical record clearly indicates that financial crises are negative shocks to demand.

References

Benguria, F, and A M Taylor (2019), “After the Panic: Are Financial Crises Demand or Supply Shocks? Evidence from International Trade”, NBER Working Paper 25790.

Jordà, Ò, M Schularick, and A M Taylor (2013), “When Credit Bites Back”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 45(s2): 3–28.

Jordà, Ò, M Schularick, and A M Taylor (2016), “The great mortgaging: housing finance, crises and business cycles”, Economic Policy 31(85): 107–152.

Mian, A, A Sufi, and E Verner (2017), “Household Debt and Business Cycles Worldwide”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(4): 1755–1817.

Reinhart, C M, and K S Rogoff (2009), “The Aftermath of Financial Crises”, American Economic Review 99(2): 466–72

Reinhart, C M, and K S Rogoff (2011), “From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis”, American Economic Review 101(5): 1676–1706.

Schularick, M, and A M Taylor (2012), “Credit Booms Gone Bust: Monetary Policy, Leverage Cycles, and Financial Crises, 1870–2008”, American Economic Review 102(2): 1029–1061.