Concerns about the dislocation of workers are widespread in developed economies, where the recent focus has been on labour market polarisation – the phenomenon of rising wages and employment gains for high- and low-skilled labour relative to middle-skilled labour (Autor and Dorn 2013, Goos et al. 2014). The leading explanation that has emerged to explain polarisation is ‘routinisation’. Middle-skilled workers perform routine tasks easily automated by information and computer technology (ICT), which has resulted in their pronounced job displacement and weak wage growth as the real price of computer capital has declined precipitously (Acemoglu and Autor 2011).

Evidence that routinisation lies behind polarisation has been documented for many developed economies, among them the US, Japan, and a number of western European economies (e.g. Spitz-Oener 2006, Autor and Dorn 2013, Michaels et al. 2013, Goos et. al. 2014, Ikenaga and Kamibayashi 2016). To date, however, little is known about the incidence of routinisation in emerging markets, and whether the worldwide diffusion of technology has – or will – result in polarising their labour markets. As hosts to a sizable fraction of the global labour force, the implications of routinisation in emerging markets for jobs, growth, and inequality could be profound, bringing with it premature deindustrialisation and disrupting income convergence (Rodrik 2016, Berg et al. 2018, IMF 2018).

How exposed are jobs in emerging markets to automation by ICT? What current indicators of the labour market can we draw on to assess their prospects for polarisation? What do recent trends hold for the erosion of middle-skilled jobs in these economies? The answers to such questions are highly relevant for the design of education, industrial, and public welfare policies in emerging markets.

The exposure to routinisation in emerging and developed economies

In a new paper, Benjamin Hilgenstock and I propose a measure of the exposure to routinisation – that is, the risk of labour displacement by information technology – that can help answer such questions (Das and Hilgenstock 2018). Combining the intrinsic potential for routinisability of an occupation with its employment share, the exposures measure how intensive a country is in the labour input of routine tasks, and thus the extent to which jobs are at risk of being routinised. Drawing on national censuses and labour surveys for 160 countries between 1960 and 2015, we establish new facts about the exposures to routinisation around the world, uncovering systematic differences between the level and dynamics of exposures in emerging and developed economies, and draw out their implications for polarisation.

A first finding is that labour in emerging markets is significantly less exposed to routinisation than labour in developed countries and remained less exposed for the quarter-century between 1990 and 2015. This finding is consistent with the widely held view that production is less capital-intensive in emerging markets, where jobs are concentrated in manual, low-skilled tasks intrinsically indisposed to automation.

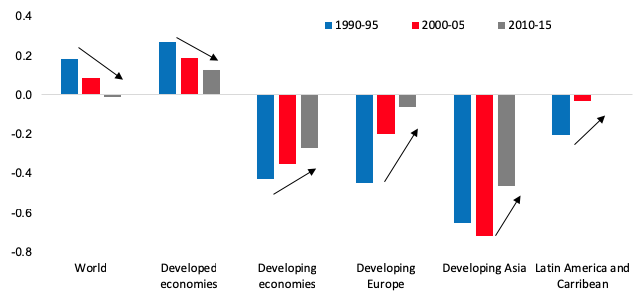

Second, the initial exposure to routinisation contains important signals about the long-run shifts in the distribution of routine employment and thus the prospects for polarisation. However, we identify a sharp asymmetry by stage of economic development: among developed economies, which were heavily exposed to routinisation to start with, the higher the initial exposure, the lower the subsequent exposure. But among emerging economies, which had initially low exposures to routinisation, the higher the initial exposure, the lower the subsequent rise in exposure. Figure 1 illustrates this striking difference in the evolution of exposures since 1990.

Figure 1 Evolution of the exposure to routinisation, 1990-2015

Notes: Initial routine exposure is measured in 1990-95. Change in routine exposure is the latest exposure in 2010-15 less initial exposure.

Sources: see Das and Hilgenstock (2018).

What lies behind these divergent evolutions of the exposure to routinisation and what do they portend? In developed economies, where initial exposures were high, consistent with the literature we find that the falling price of automating technology – along with the offshoring of routine-intensive jobs to cheap-labour locations – led to an intense displacement of routine labour, making the marginal task less routine, thus lowering routine exposure. Both dimensions matter: in countries where initial exposures were about equivalent, those which experienced greater declines in the price of capital also saw greater declines in exposures, while among countries which faced about the same decline in the price of capital, those with higher initial exposures generally found themselves subsequently less exposed to routinisation.

In emerging markets, by contrast, the price of capital experienced little to no decline in this period and we identify two other forces behind rising exposures to routinisation: the ongoing structural transformation of these economies, and the globalisation of trade. Structural transformation has moved labour from non-routine jobs in agriculture to routine-intensive manufacturing and service jobs (Bárányi and Siegel 2018), and this phenomenon has been compounded by the surge in offshoring which has transferred routine-intensive factory and service jobs from developed countries to their developing counterparts (Blinder and Krueger 2013, Lian 2018). These findings are new to the literature on polarisation and present an interesting contrast to the well-researched forces behind routinisation in developed economies.

Implications of rising exposures to routinisation in emerging markets

An important consequence of the asymmetric evolutions of the exposure to routinisation in developed versus emerging markets is a worldwide convergence in exposures, as the exposure to routinisation in emerging economies rise toward levels once seen in developed nations (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Trends in exposure to routinisation across the world

Source: Data from Das and Hilgenstock (2018).

What do these trends hold for the future of labour markets in emerging markets? An immediate implication is that their labour markets are becoming increasingly exposed to technological disruptions. The lessons from developed economies suggests that rising exposure to routinisation has the potential to trigger labour market dislocations on a significant scale, especially considering the pace at which some large emerging markets are already automating production. Further declines in the cost of capital may also induce developed economies to automate rather than offshore jobs, reinforcing job losses that could arise from automation in emerging markets. Such technological dynamics could erode middle-skilled employment earlier in the convergence process than in developed economies, bringing it with premature deindustrialisation (Maloney and Molina 2016, Rodrik 2016).

However, our analysis underscores that such dislocations are likely to be episodic in the near-term, sporadically arising in some large manufacturing industries in a few large emerging markets, but not widespread to disrupt emerging labour markets on a macro-significant scale over at least the next five years. This is because rising exposure to routinisation does not in and of itself precipitate job losses without a clear pecuniary trigger such as a sharp drop in the relative price of capital, and the ongoing offshoring of jobs (though slowing) continues to raise demand for routine labour in emerging markets. Furthermore, although a few export hubs in Asia are experiencing wage escalation, in emerging markets as a whole the price of investment goods is forecasted to remain contained and significantly higher than labour and other factor costs for some time to come (Das and Hilgenstock 2018).

Conclusions

In this column we combine data on the routine-intensity of occupations with the occupation distribution of employment to construct a country’s exposure to routinisation, and illustrate that the initial exposure to routinisation has predictive power for future labour market developments Drawing on a cross-country time series of exposures, our analysis suggests that although large-scale labour market dislocation is not imminent, emerging markets are becoming increasingly exposed to routinisation – and thus labour market polarisation – from the long-term effects of structural transformation and the onshoring of routine-intensive jobs.

The database on exposures to routinisation has widespread applicability on topics beyond labour market polarisation. As the exposure to routinisation in an initial period is exogenous to subsequent shocks, the cross-country heterogeneity of exposures provides important variation in answering questions about the long-run causal impact from technological advancements in information technology on macroeconomic outcomes. These data have recently been used to quantify the impact of the initial exposure to routinisation on the labour share of income (Dao et. al. 2017), labour force participation (Grigoli et al. 2018), middle-class income (Nakamura 2018), and youth unemployment (Ahn et. al. forthcoming).

Author’s note: The views expressed herein are those of the author and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Acemoglu, D and D H Autor (2011), “Skill, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings”, in Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4, Elsevier.

Ahn,J, Z An, J Bluedorn, G Ciminelli, Z Koczan and D Muhaj (forthcoming), “Youth Labor Market Prospects in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies: Drivers and Policies”, IMF Staff Discussion Note.

Autor, D H and D Dorn (2013), "The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market", American Economic Review 103(5): 1553–1597.

Bárányi, Z and C Siegel (2018), “Job polarization and structural change”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 10: 57-89.

Berg, A, E Buffie and F Zanna (2018), “Should We Fear the Robot Revolution? (The Correct Answer is Yes)”, IMF Working Paper WP18/116.

Blinder, A and A Krueger (2013), "Alternative Measures of Offshorability: A Survey Approach," Journal of Labor Economics 31(S1): S97 - S128.

Dao, M, M Das, Z Koczan and W Lian (2017), “Why is Labor Receiving a Smaller Share of Global Income? Theory and Evidence”, Working Paper.

Das, M and B Hilgenstock (2018), “The Exposure to Routinization: Labor Market Implications for Developed and Developing Economies”, IMF Working Paper.

Goos, M, A Manning and A Salomons (2014), “Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring”, The American Economic Review 104(8): 2509–2526.

Grigoli, F, Z Koczan and P Topalova (2018), “A Cohort-Based Analysis of Labor Force Participation for Advanced Economies”, IMF Working Paper WP/18/120.

IMF (2018), Technology and the Future of Work.

Ikenaga, T and R Kamibayashi (2016), “Task Polarization in the Japanese Labor Market: Evidence of a Long-Term Trend”, Industrial Relations 55: 267–293.

Lian, W (2018), “Task Trade and Global Labor Share”, Working Paper.

Michael, G, A Natraj, and J Van Reenen (2013), “Has ICT Polarized Skill Demand? Evidence from Eleven Countries over 25 Years”, NBER Working Paper No. 16138.

Maloney, W and C Molina (2016), “Are Automation and Trade Polarizing Developing Country Labor Markets, Too?”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7922.

Nakamura, T (2018), “Why is the American Middle Class Vanishing”, Working Paper, Kobe Gakuin University.

Rodrik, D (2016), "Premature deindustrialization", Journal of Economic Growth 21(1): 1-33.

Spitz‐Oener, A (2006), "Technical Change, Job Tasks, and Rising Educational Demands: Looking outside the Wage Structure", Journal of Labor Economics 24(2): 235-270.