In the aftermath of the Global Crisis, several central banks in advanced economies have sought to provide a major and prolonged stimulus to economic activity. They have kept policy rates at, or close to, the effective lower bound, engaged in forward guidance, and carried out large-scale asset purchases. As a result, not only short-term but also long-term interest rates have declined to historically low levels, sometimes drifting into negative territory. Such an environment should have an impact on banks’ business. How do they adjust?

The question matters. It is well known that low interest rates tend to compress net interest margins. There is a limit to how far deposit rates can decline so that, after a point, any further cut in loan rates cannot compensate their reduction (Claessens et al. 2018, Borio et al. 2017). To be sure, a decline in interest rates will boost valuations and hence profits, but the effect dissipates over time while lower margins stay (Bernanke and Kuttner 2005). This is important, since lower profitability saps a bank’s first line of defence against losses, making it harder to accumulate capital and hence to lend (Gambacorta and Shin 2018, Borio and Gambacorta 2017).

To understand how banks adjust, in a recent study we analyse the financial statements of 113 large international banks headquartered in 14 major advanced economies over the period 1994–2015 (Brei et al. 2019). The sample covers assets worth $53 trillion at end-2015 and represents more than 70% of global bank intermediation.

A first look: Simple correlations

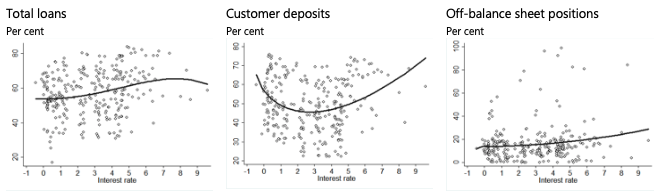

Consider simple correlations first. Considerable bank heterogeneity aside, the evidence indicates that, on balance, banks change the composition of their activity towards fee-generating business and trading. At very low rates, banks’ interest income declines while the income related to fees and trading increases (Figure 1).

The shift, however, is not sufficient to compensate for the fall in net interest margin. Largely as a result, return on assets falls.

Figure 1 Interest rates and bank income structure (%)

Note: The scatter plots show annual country averages of bank-level indicators. Interest income is interest income on loans excluding dividend income as a percentage of total income. Fee and trading income defined as net fees and commissions and net gains on trading and derivatives as a percentage of total income. Return on assets is net income divided by total assets. The horizontal axis shows the short-term interest rate.

Sources: Fitch Connect; Bloomberg; Datastream; national data. Authors’ calculations.

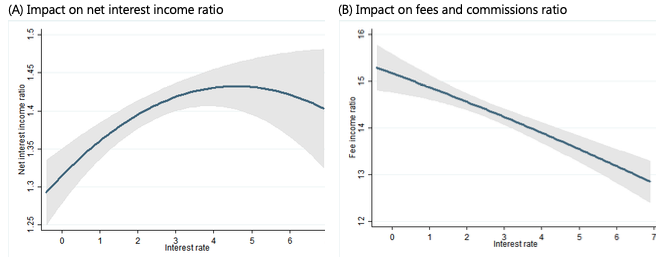

Low interest rates should also induce banks to adjust their balance sheets, in part reflecting their shifting business. Banks may move away from traditional loan-making business to other earning assets (e.g. stocks, bonds) or readjust off-balance sheet activity. They may rely relatively more on stable forms of funding, such as deposits and fixed-rate long-term debt, rather than on short-term variable-rate funding. They may hold more cash and likely liquid assets, not least as central banks tend to increase the volume of excess reserves in the system, which banks are forced to absorb. Given favourable financial conditions and receptive capital markets, banks may find that companies demand less liquidity insurance, such as in the form of committed credit lines, and guarantees against the default of third-party debt.

Simple correlations confirm this overall picture (Figure 2). On the asset side, banks appear to shift from loans to other earning assets, and on the liability side from short-term/variable-rate market funding to deposits. And heterogeneity aside, off-balance sheet activity seems to decline, possibly because of a drop in guarantees.

Figure 2 Interest rates and balance sheets

Note: The scatter plots show annual country averages of bank-level indicators. Total loans expressed as a percentage of total earning assets. Customer deposits expressed as a percentage of total funding. Off-balance sheet positions include securitised assets, guarantees, acceptances and credit lines expressed as a percentage of total exposure (ie the denominator of the Basel III leverage ratio). The horizontal axis shows the short-term interest rate.

Sources: Fitch Connect; Bloomberg; Datastream; national data. Authors’ calculations.

A deeper look: Regression analysis

In the regression analysis, we focus on 12 balance sheet indicators. As controls, we include variables that capture the macro-financial and regulatory environment as well as a number of bank-specific characteristics such as leverage and liquidity profile. We also allow for the possibility that the relationship between interest rates and the indicators is non-linear and depends on the duration of low interest rates.

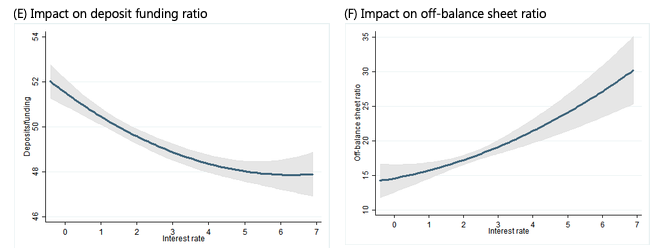

The econometric results confirm the previous impression (Figure 3). When interest rates decline and reach the zero lower bound, banks’ net interest income ratios fall (panel A) while those income generated by fee-based and trading increase (panels B and C). Similarly, on the asset side, the incidence of available-for-sale securities and cash rises (panel D); and on the liability side, reliance on deposits increases (panel E). Interestingly this effect is larger in case of a prolonged period of low interest rates. Finally, off-balance sheet exposures decrease (panel F), due to the reduction in guarantees offered to customers.

Figure 3 Effect of the short-term interest rate on bank intermediation activity

Note: The panels show the marginal effect of the short-term interest rate on (I) net interest income in % of total exposure, (II) net fees and commissions in % of total income, (III) net gains on trading and derivatives in % of total income, (IV) available-for-sale securities plus cash in % of total exposure, (V) total deposits in % of total funding, and (VI) off-balance sheet exposures in % of total exposure. The shaded area indicates 95% confidence bands. Detailed results can be found in Table 4 of Brei et al (2019).

Low interest rates also go hand-in-hand with significant changes in banks’ risk profiles (Figure 4). In particular, the overall riskiness of portfolios drops (panel A), at least as measured by the risk density function (risk-weighted assets divided by total exposure). The result is stronger for capital-constrained banks, which have greater incentives to restore their prudential capital ratio and experience a significant decline in the loan-to-assets ratio. Loan loss provisions also decline (panel B), possibly a sign of evergreening.

Figure 4 Effect of the short-term interest rate on bank risks

Note: The panels show the marginal effect of the short-term interest rate on (I) risk-weighted assets in % of total exposure and (II) loan impairment charge in % of total loans. The shaded area indicates 95% confidence bands. Detailed results can be found in Table 4 of Brei et al (2019).

Conclusion

Our results are mixed news for financial stability and for banks’ capacity to support economic activity through lending. Less risky portfolios, combined with higher capitalisation, strengthen banks’ resilience and lending capacity. But lower profitability may make them more vulnerable and less able to provide loans in the longer term (BIS 2019).

References

Bank for International Settlements (2019), Annual Economic Report 2019, Basel.

Bernanke, B and K Kuttner (2005), “What explains the stock market's reaction to Federal Reserve policy?“, Journal of Finance 60(3): 1221–57.

Borio, C, L Gambacorta and B Hofmann (2017), “The effects of monetary policy on bank profitability”, International Finance, 20: 48–63.

Borio, C and L Gambacorta (2017), “Monetary policy and bank lending in a low interest rate environment: diminishing effectiveness?”, Journal of Macroeconomics 54B: 217–31.

Brei, M, C Borio and L Gambacorta (2019), “Bank intermediation activity in a low interest rate environment”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13980 and BIS Working Paper 807.

Claessens, S, N Coleman and M Donnelly (2018), “Low-For-Long interest rates and banks’ interest margins and profitability: Cross-country evidence”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 35A: 1–16.

Gambacorta, L and H S Shin (2018), “Why bank capital matters for monetary policy”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 35B: 17–29.