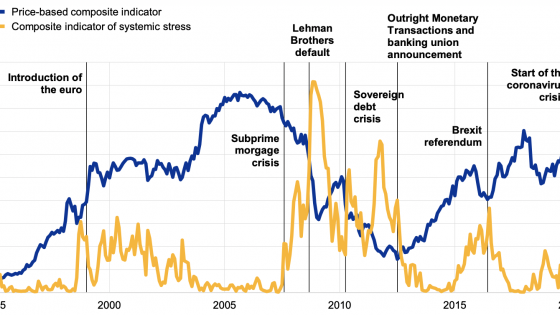

When the COVID-19 crisis hit in March 2020, bond markets faced a large sell-off. This was partially driven by mutual funds that suffered investor redemptions (e.g. Falato et al. 2021, Breckenfelder et al. 2021).

To satisfy redemptions, mutual funds had to sell some of their assets, mostly bonds. Typically, dealer banks absorb such pressure from fire sales, but this did not seem to happen in March 2020, leading to stress in even the most liquid markets such as the US Treasury market.

Market stress in March 2020 has been linked to a variety of factors. One such factor is dealer bank balance sheet constraints due to leverage ratio regulation (e.g. Duffie 2020, He et al. 2020). Leverage ratio regulation requires banks to hold capital against all on- and off-balance sheet exposures, regardless of their risk. This regulation may lead dealer banks to reduce balance sheet space available for market-making owing to low margins. Less market-making by banks can manifest itself in market illiquidity, particularly during episodes of stress (Bao et al. 2018, Dick-Nielsen and Rossi 2019).

The importance of the leverage ratio as a contributing factor to the market stress was underscored by the US Federal Reserve’s move to temporarily change its supplementary leverage ratio rule on 1 April 2020 to “ease strains in the Treasury market resulting from the coronavirus and increase banking organisations’ ability to provide credit to households and businesses”.1

In a recent paper (Breckenfelder and Ivashina 2021), we provide an empirical perspective to answer the following question: did bank leverage constraints amplify bond market illiquidity during the March 2020 crisis?

The large outflows from mutual funds (‘runs’) in March 2020 provide a key economic setting to study the role of dealer banks’ balance sheet constraints in propagating financial fragility by amplifying the run dynamics and sell-offs. The specific mechanism at play for mutual funds was articulated by Goldstein et al. (2017) and more recently by Ma et al. (2020). The basic idea is that runs on some classes of assets expose mutual funds holding such assets to significant fund outflows. To satisfy outflows, funds are forced to sell off assets.

To document the above dynamics, our analysis links mutual funds and their bond holdings to dealer banks and their leverage constraints. We link individual bonds to dealer banks by exploiting two economic mechanisms. The first is related to the fact that the bulk of a country’s bonds are likely to be transacted by that country’s domestic dealer banks. The second stems from the fact that if Bank A was the underwriter of the Firm B bond issue, it is very likely that Bank A is also the key dealer for these bonds long after the initial placement. This allows us to introduce quasi-exogeneity in assignment of dealers to individual bonds and test whether dealers’ constraints matter for individual bonds and, ultimately, for mutual fund portfolios.

We measure bank balance sheet constraints by looking at the dealer bank’s distance to the regulatory leverage constraint. Our analysis exploits cross-sectional differences in fund exposure to dealers’ balance sheet constraints and traces its impact on fund flows and sell-off pressures.

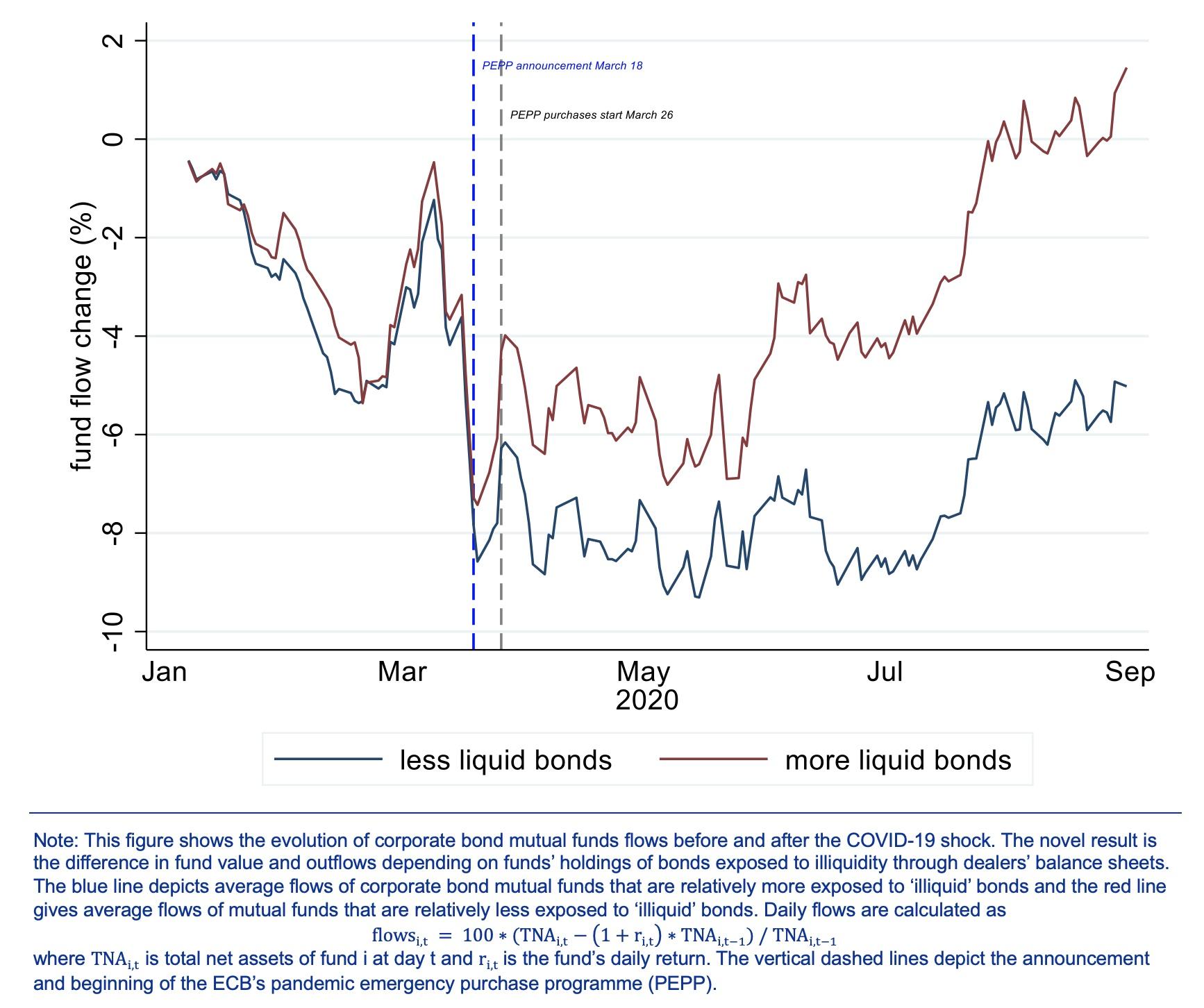

For fund flows, we document that funds more exposed to bank balance sheet constraints suffered higher outflows compared with less exposed funds (Figure 1). Leading up to March 2020, all funds closely tracked each other in terms of fund flows (and performance, not shown in Figure 1), but the COVID-19 shock resulted in decoupling, with more exposed funds emerging as particularly affected.

Figure 1 Changes in corporate bond fund flows

For sell-off pressures, our hypothesis is that – conditional on their pre-crisis cash positions – mutual funds that were relatively more exposed to dealer banks with more severe balance sheet constraints faced higher sell-off pressures in their liquid bonds.

Our results confirm that investment into liquid bonds drops by 1.27% for funds relatively more exposed to dealers with lower market-making capacity. Specifically, the average fund holding of liquid bonds for these funds is 22.97%. This implies that liquid bond holdings decline by 5.5% (=100*1.27/22.97) more for funds with exposure to bank balance sheet constraints.

How does the leverage ratio affect bond market liquidity?

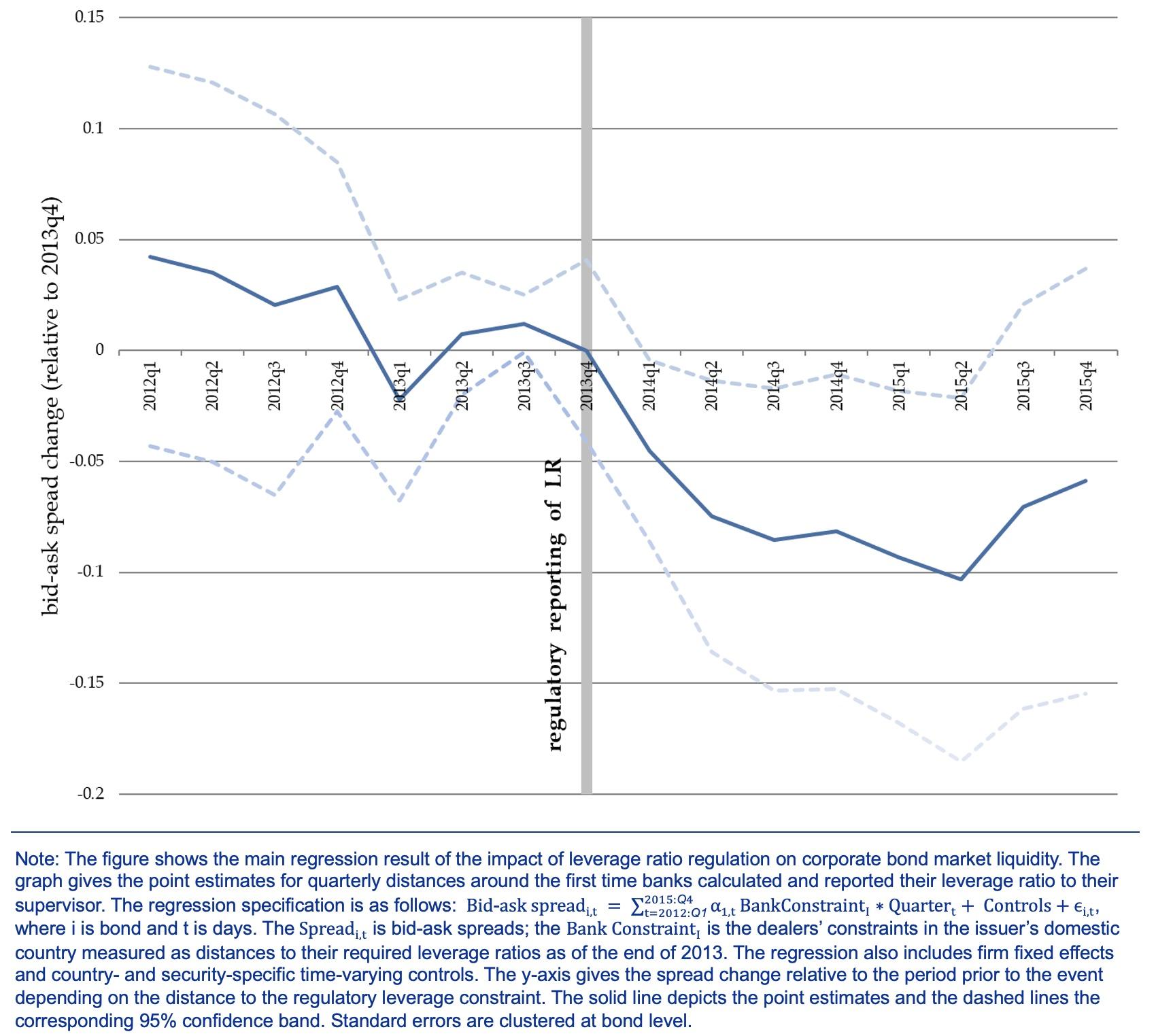

We provide supplementary evidence that dealer banks’ regulatory constraints affect bond liquidity, using the same matching between bonds and dealers based on (i) home bias, and (ii) past bond underwriting relationships. For this analysis, we focus on the period around 31 December 2013. As of this date, the leverage ratio became effectively binding for euro area banks for the first time, in view of the 2014 Comprehensive Assessment exercise.2 We compare the shift in liquidity for the same bond two years before and two years after the leverage ratio first had to be reported to bank supervisors.

Using the home bias matching, we find that for countries where dealer banks are 1% closer to the regulatory requirement (about one standard deviation), the bid-ask spread is 8 basis points higher (about 25% of the median bid-ask spread in our sample). This result is robust to several ways of identifying a dealer bank in the data, and to constructing bank balance sheet constraints at the bond level.

We also show that the effect comes through the domestic dealer banks, but not through other domestic banks. We control for a range of contemporaneous macro variables including a bond’s domestic country GDP growth, domestic equity market and domestic banking sector growth, domestic volatility index, and sovereign spreads. This helps us to make sure that bond liquidity and the banks’ constraints are not trivially correlated in the country-level analysis.

Using the past underwriter relationships, we find that if a bond dealer with existing underwriting ties is 1% closer to the regulatory requirement, the bid-ask spreads of the bond increase by 4 basis points (about 6.8% of the mean).

Figure 2 Impact of the leverage ratio on bond market liquidity

Conclusion

Mutual fund runs in the US and Europe in 2020 put unprecedented pressure on the bond market and culminated in sweeping policy interventions designed to stabilise the markets on both sides of the Atlantic. We started off by asking to what extent bank balance sheet constraints due to the leverage ratio had added to the mutual fund instability and sell-off pressures. We show that, during the 2020 run episode, mutual funds with larger exposures to bank balance sheet constraints faced bigger redemptions and pressure to sell off liquid bonds.

While leverage ratio regulation introduced in the aftermath of the global financial crisis aimed to make banks more resilient, our analysis highlights that it can have side effects for market functioning, particularly in times of stress. To alleviate such side effects, both the Federal Reserve and the Eurosystem moved to temporarily change their respective leverage ratio rules in 2020. This episode suggests that the optimal leverage ratio is procyclical.

Authors’ note: This column first appeared as a Research Bulletin of the European Central Bank. The authors gratefully acknowledge comments and suggestions from Alexander Popov and Louise Sagar. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank or the Eurosystem.

References

Bao, J, M O’Hara and X Zhou (2018), “The Volcker rule and market-making in times of stress”, Journal of Financial Economics 130(1): 95-113.

Breckenfelder, J and V Ivashina (2021), “Bank Balance Sheet Constraints and Bond Liquidity”, Working Paper Series, No 2021/2589, ECB.

Breckenfelder, J, N Grimm and M Hoerova (2021), “Do non-banks need access to the lender of last resort? Evidence from mutual fund runs”, SSRN working paper.

Dick-Nielsen, J and Rossi, M (2019), “The cost of immediacy for corporate bonds”, Review of Financial Studies 32(1): 1-41.

Duffie, D (2020), “Still the world’s safe haven? Redesigning the U.S. Treasury market after the COVID-19 crisis”, Hutchins Center Working Paper No 62, Brookings Institution.

Falato, A, I Goldstein and A Hortaçsu (2021), “Financial fragility in the COVID-19 crisis”, Journal of Monetary Economics 123: 35-52.

Goldstein, I, H Jiang and D T Ng (2017), “Investor flows and fragility in corporate bond funds”, Journal of Financial Economics 126(3): 592-613.

He, Z, S Nagel and Z Song (2020): “Treasury inconvenience yields during the COVID-19 crisis”, Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

Ma, Y, K Xiao and Y Zeng (2021), “Mutual fund liquidity transformation and reverse flight to liquidity”, Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

Endnotes

1 The Federal Reserve press release from 1 April 2020 can be found at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20200401a.htm.

2 The Comprehensive Assessment was the first standardised euro-area-wide assessment of the health of bank balance sheets.