The decades before the Global Crisis of 2007 to 2009 were characterised by profound financial deregulation. There was a major relaxation in the structure (determining the activities that could be undertaken) and conduct (specifying business practices) rules for banking in most developed countries. Deregulation, coupled with financial innovation, altered the business models and the incentives to take on new risks for banks. Efficiency and competition took precedence over financial stability (Vives 2016).

Capital as the solution?

The regulatory answer to these new incentives mostly focused on capital requirements. Efforts to improve supervision started with the Basel I Accord, which proposed minimum common capital requirements, and continued with the Basel II and Basel III Accords, which increased the sophistication of bank capital rules.

The forthcoming revised Basel III Accord is expected to rely on capital-based regulations, as well as on better liquidity buffers. The Global Crisis has also led to more use of stress tests in the supervisory community. Stress tests are also ultimately a capital-based tool, as solvency is ‘tested’ against some ‘stress’ scenarios and the institutions ‘failing’ to pass those tests must set aside additional capital.

The increased reliance on capital is intended to improve bank buffers to withstand losses. From a static perspective, by assigning capital weights to each business activity, supervisors are supposed to adjust the amount of capital that banks must set aside to reflect the amount of risks taken. Under normal conditions, more capital would also shrink the incentives that bankers have to take on excessive risks, because they would have more of their own capital at stake.

In a dynamic context, however, relying on a single supervisory tool to support financial stability may be risky. Any supervisory tool affects the behaviour of agents in an uncertain way, and may be difficult to calibrate for several reasons:

- Information asymmetries: The difference in information available to bankers and external observers imply that it would be hard for any supervisor, no matter how qualified, to precisely assess prudential requirements of large and complex financial institutions.

- Limited supervision resources: Supervisors tend to have significantly less resources (financial and technical) than bankers and supervisors themselves are subject to their own set of incentives (Prendesgast 2003).

- Unintended consequences: In certain circumstances (such as very high competition), banks might react to increased prudential requirements by taking on more risk (Uluc and Wieladek 2017).

A robust supervisory framework would require a variety of supervisory tools to deal with the uncertainty surrounding their precise effects.

Rate of credit expansion predicts bank risk

In a new paper, we study which bank characteristics before 2007 helped to predict realised risk during the crisis (Altunbas et al. 2018). Using a large sample of banks, we find that undercapitalised institutions were more likely to default. Above a certain threshold, however, a bank's capital was an insignificant predictor of ability to withstand the crisis. By far the most important determinant of bank risk was the rate of credit expansion. When we examine the different components of the credit expansion, real estate exposure played a major role for the systemic dimension of bank risk.

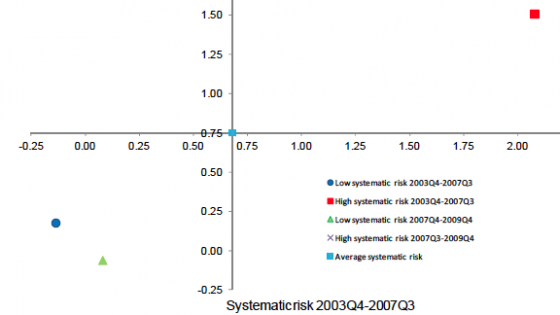

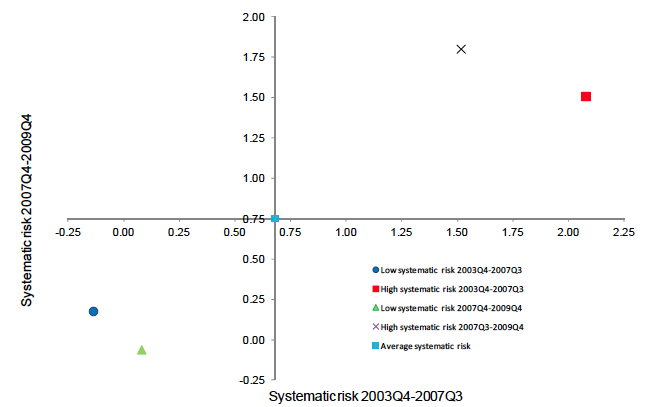

Using measures of risk calculated prior to the Global Crisis gives the same result. Figure 1 shows that banks with high levels of systematic risk before the crisis had higher realised risk during the crisis. This implies high persistence for systematic bank risk. We find that similar bank characteristics were important determinants of systematic risk before the crisis. This suggests that cyclical indicators such as relative credit growth would provide useful additional information for supervisors.

Figure 1 Scatter plots of systematic risk levels during pre-and post-crisis

Source: Altunbas et al. (2018).

Note: The horizontal axis shows the average systematic risk during the pre-crisis period (2003Q4 to 2007Q3) for the bottom 5% (low risk) and the top 95% (high risk) banks. The vertical axis reports the average realised systematic risk for the same group of banks between 2007Q4 and 2009Q4. Systematic risk measures were constructed using a capital asset pricing model (Altunbas et al. 2018).

Policy implications when strengthening supervision

In response to the effects of excessive fluctuation in credit and housing cycles, authorities in developed countries followed some developing countries in adopting macroprudential tools to contain systemic risks. The idea was that these tools would be ‘countercyclical’ and attenuate the negative externalities of more volatile financial cycles. Guiding principles of macroprudential policies are that they should be pre-emptive and act forcefully to smoothen the financial cycle (Constâncio 2016).

Yet, to act forcefully, major macroprudential authorities should also be given a variety of tools (ECB 2016). In the Eurozone for instance, the current regulatory supervisory framework for banks – the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV) – does not provide the central macroprudential authority (the ECB) with the ability to combine capital-based tools with other instruments. The ECB does not have the power to implement borrower-based macroprudential tools, which remain the sole responsibility of national authorities (Claessens 2014). This restriction might be costly, particularly if there were coordination problems or if responsible authorities did not have an incentive to internalise the externalities of their actions. A similar situation exists in the US, where the deployment of borrower-based instruments would not be part of the remit of the Federal Reserve Board, the main macroprudential supervisor.1

Borrower-based measures can, however, usefully attenuate household indebtedness. This is important, because house-price booms associated with increased borrower leverage have been found to be the most destructive (Cerutti el al. 2016).

While increasing banks’ capital buffers would be helpful to buttress financial stability, banking everything on capital may turn out to be a risky bet.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, or imply any responsibility for, the ECB. We are grateful to Juan Segurado, Matthias Sydow, Skander Van den Heuvel and Thomas Vlassopoulos for helpful discussions.

References

Altunbas, Y, S Manganelli and D Marques-Ibanez, D (2018), "Realized Bank Risk during the Great Recession", Journal of Financial Intermediation, forthcoming.

Cerutti, E, S Claessens and L Laeven (2017), "The Use and Effectiveness of Macroprudential Policies: New evidence", Journal of Financial Stability 28(C): 203-224.

Claessens, S (2014), "An Overview of Macroprudential Policy Tools", IMF Working Paper 14/214.

Constâncio, V (2016), "Principles of Macroprudential Policy", Speech by Vice-President of the ECB, at the ECB-IMF Conference on Macroprudential Policy, Frankfurt am Main, 26 April.

European Central Bank (2016), ECB Contribution to the European Commission’s Consultation on the Review of the EU Macroprudential Policy Framework.

Prendesgast, C (2003), "The Motivation and Bias of Bureaucrats", American Economic Review 97(1): 180-96.

Uluc, A and T Wieladek (2017), "Capital Requirements, Risk Shifting and the Mortgage Market", European Central Bank Working Paper 2061.

Vives, X (2016), Competition and Stability in Banking: The Role of Competition Policy and Regulation, Princeton University Press.

Endnotes

[1] The use of borrower-based tools would be the responsibility of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, whose main responsibility is consumer protection, rather than financial stability.