There is a large body of research based on Okun (1962) in which researchers (like Okun himself) approach the relationship the law specifies in different ways. Most common are the ‘difference approach’ (i.e. examining the relationship between the change in the unemployment rate and output growth) and the ‘gap approach’ (i.e. examining the relationship between the deviation of the actual from the natural or equilibrium unemployment rate, on the one hand, and the gap between the level of actual and potential output on the other).

Recent research on US data has focused on the magnitude, the stability, and the asymmetry of the Okun coefficient over the economic cycle. Owyang and Sekhposyan (2012) show that during recent US recessions – including the Great Recession – unemployment appears to be more sensitive to economic growth than before. Cazes et al. (2013) also find that the Okun coefficient varies over time and appears to be larger during recessions than during expansions. Pereira (2013) concludes that there are asymmetries in the Okun relationship with a weaker relationship during periods of expansion. Valadkhani and Smyth (2015) also find asymmetries and a weakening of the Okun relationship since the early 1980s. Furthermore, Belaire-Franch and Peiro (2015) conclude that there is an asymmetry in the relationship between unemployment and the business cycle. Finally, Ball et al. (2017) find that Okun’s law is a strong, reliable and stable relationship and that a constant (not time-varying) Okun coefficient is a good approximation to reality.

In a recent paper (Lim et al. 2018), we look at the relationship between changes in the unemployment rate and output growth through the lens of US labour market flows. As far as we know, no one has utilised flows data in this context, yet clearly the change in the unemployment rate reflects the balance of flows into and out of unemployment within a period. Therefore it is natural to look at the Okun relationship as one between output growth and labour market flows. Our analysis is based on the ‘difference approach’ to Okun’s law, since labour market flows are informative about the change in the unemployment rate. We also propose focusing on net flows (the balance of the gross flows between any two states) as they more effectively highlight the dynamics (including asymmetries) behind the evolution of the Okun coefficient.

The flows framework provides an encompassing structure to study the relationship between GDP growth and changes in the unemployment rate and in particular, the conditions under which the Okun coefficient (i.e. the coefficient linking the change in the unemployment rate to the output growth rate) is time-varying and/or asymmetric, i.e. the change in the unemployment rate differs for positive/negative shocks to growth. Furthermore, the flows approach allows us to adopt a three-state analysis – namely, flows between employment, unemployment and not in the labour force. Thus we study how shocks to growth affects labour flows and how they, in turn, translate into changes in three summary statistics – the unemployment rate, the participation rate and the employment–population ratio.

Okun’s law: A flows approach

There are six gross flows in a labour market with three states: employment (E), unemployment (U) and out of the labour force (N). In our data set, the (contemporaneous) correlation between the gross flows is very high: 0.70 between EU and UE, 0.95 between NU and UN, and 0.87 between EN and NE. Hence, rather than use highly correlated gross flows, we use net flows, the balance of movements between any two labour market states.

In our empirical analysis, we relate the three net labour market flows to changes in GDP growth and the lagged unemployment rate, allowing for asymmetrical effects of both GDP growth and the lagged unemployment rate (for details, see our paper). Since October 2007, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has made available estimates of gross flows consistent with the evolution of labour market stocks. These series extend from February 1990 to the present. The net flows can be easily computed from the data on the gross flows.

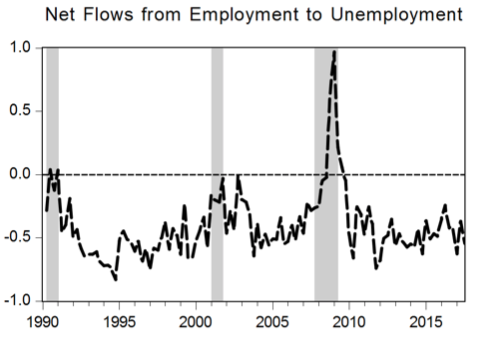

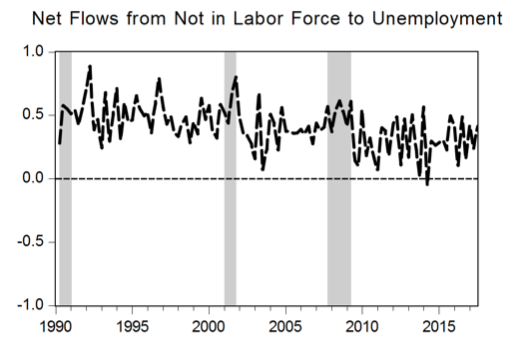

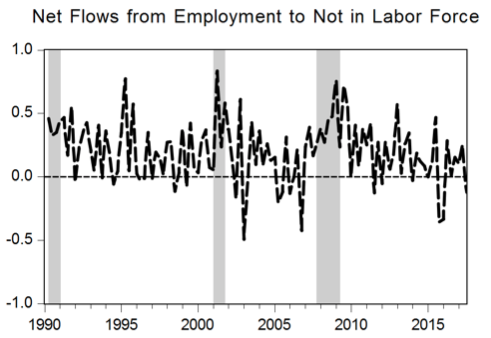

Figure 1 Net flows of employment to unemployment, not in the labour force to unemployment, and employment to not in the labour force, 1990:2-2017:3

Note: Shaded areas are the NBER recession periods

Figure 1 shows the evolution of each of the net flows over the period 1990:2 to 2017:3. We see three things. First, the balance of flows from employment to unemployment is negative, except during two quarters in the early nineties and especially during the Great Recession when there was a marked rise. Second, except for 2014:2, the balance of flows from not in the labour force to unemployment is positive, and this is the case even in downturns, Third, in most quarters the balance of flows from employment to not in the labour force is positive.

Our parameter estimates show that only the net flow from employment to unemployment responds (negatively) to the contemporaneous growth of real GDP and that it does so with a significant asymmetric effect, i.e. an increase in growth reduces this net flow by less than a falling growth increases net flow. The two other net flows are not directly responsive to growth. An increase in the lagged unemployment rate affects positively the net flows from employment to ‘not in the labour force’ but not the net flows from ‘not in the labour force’ to unemployment. The net flow from employment to unemployment also reacts to the lagged unemployment rate.

Focusing on the impact of growth on the change in the unemployment rate, our results show that the US Okun coefficient is asymmetric (i.e. it depends on whether growth is positive or negative), but it is not time-varying (i.e. it does not vary with calendar time). In contrast, the results also show that the dynamic effects are time-varying even though the reactions of the net flows to the lagged unemployment rate are not asymmetric. Our results also indicate that the participation rate responds to the lagged change in the unemployment rate via the net flow between employment and out of the labour force.

Contractions and expansions

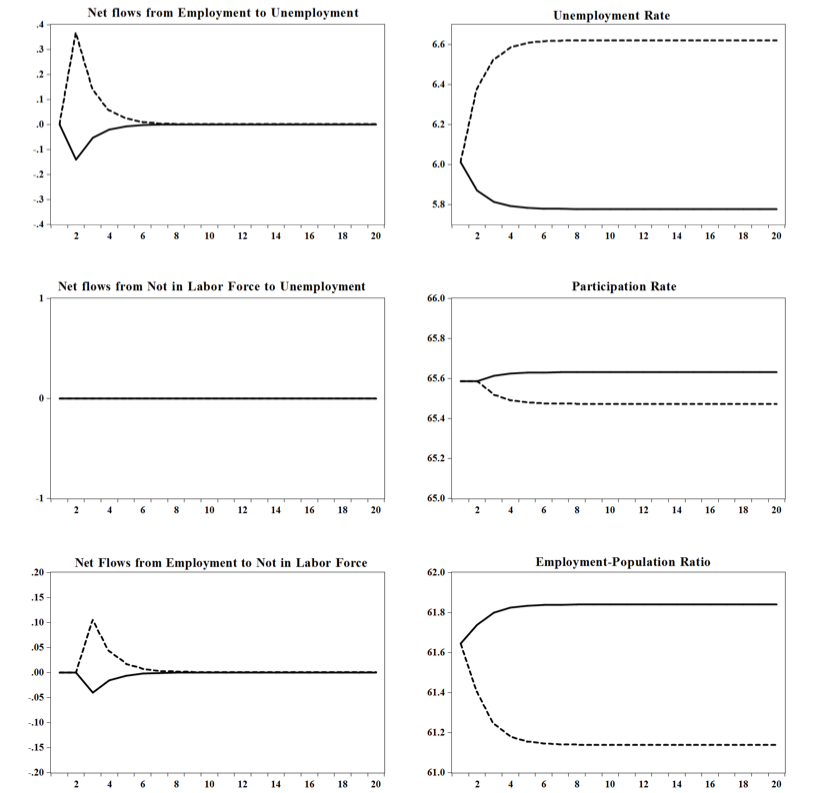

Participation rates, employment-population ratios, and unemployment rates are determined simultaneously, as a consequence of changes in the net flows. To understand the extent to which these rates change in contractions and expansions, we used our parameter estimates to simulate the dynamic paths of the three summary measures. The results of these simulations are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Simulated net flows, unemployment and participation rates and the employment–population ratio

Note: Solid lines: contractionary shock; dashed lines: expansionary shock

The figures for the net flows show that they stabilise and the directions of change are as expected. Observe that the dynamic paths of the net flow between employment and unemployment and between out of the labour force and employment are asymmetric, but the net flows from inactivity to unemployment are unaffected by growth or by lagged labour market conditions. Following a temporary shock to GDP growth, there are impact effects to the net flows from employment to unemployment, but the effects are asymmetric depending on whether the shock to growth is a 1% fall in GDP growth (contractions) or a 1% increase in GDP growth (expansions). Subsequent dynamics show that both net flows from employment react to lagged labour market conditions. The extensive literature on Okun’s law suggests that the relevant explanation(s) for asymmetry in the Okun coefficient likely reflect differences in how average hours, labour productivity, labour force participation, and the process by which workers are matched to jobs respond to positive or negative shocks to GDP. In his 1962 paper, Okun himself focused attention on the first three possibilities, while more recent literature examined asymmetries resulting from differences in job hiring and search practices, including the scaring effects of unemployment.

Concluding remarks

We proposed a labour flows framework to understand the dynamics between growth and labour market behaviour, specifically to understand Okun’s law. Using quarterly US data, we find that neither net flows from unemployment to ‘not in the labour force’ nor from employment to ‘not in the labour force’ are sensitive to changes in growth – unlike the net flows between employment and unemployment, which are sensitive to changes in growth. However, Okun’s coefficient exhibits asymmetry, being larger (in absolute terms) in contractionary periods than expansionary periods because the net flows between employment and unemployment respond differently to positive and negative changes in growth.

Simulating the model with a shock to output growth, we find that labour market flows are affected such that the long-run Okun coefficient (the change in the unemployment rate in response to a 1% change in growth) is 0.61 for a negative shock and 0.24 for a positive shock. This result likely reflects the observation that it is easier to lay-off workers in recessions than it is to hire workers in a boom, because employers tend to be hesitant about adjusting their workforce along the extensive margin, and may prefer, in the early stages of recovery, to expand along the intensive margin of labour supply by increasing overtime hours.

To conclude, we have presented an approach based on labour flows that facilitates a deeper understanding of the relationship known as Okun’s law. Our labour flows framework not only provides a natural (testable) specification to explain why an Okun coefficient may be (potentially) time-varying and asymmetric, but it also identifies the underlying flows that are critical to explaining the time variation and asymmetry.

References

Ball, L, D Leigh, and P Loungani (2017), “Okun’s law: Fit at 50?”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 49(7): 1413-1441.

Belaire-Franch, J and A Peiró (2015), “Asymmetry in the relationship between unemployment and the business cycle”, Empirical Economics 48(2): 683–697.

Cazes, S, S Verick, and F Al Hussmi (2013), “Why did unemployment respond so differently to the global financial crisis across countries? Insights from Okun’s Law”, IZA Journal of Labor Policy 2: 1-18.

Lim, G C, R Dixon, and J C Van Ours (2018), “Beyond Okun’s law: output growth and labor market flows”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13369.

Erceg, C J, and A T Leven (2014), “Labor force participation and monetary policy in the wake of the Great Recession”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 46(2): 3–49.

Okun, A (1962), “Potential GNP: Its measurement and significance”, Proceedings of the American Statistical Association, Business and Economic Statistics Section, ASA, Washington, 98–104.

Owyang, M T, and T Sekhposyan (2012), “Okun’s Law of the business cycle: was the Great Recession all that different?”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 94(5): 399-418.

Pereira, R M (2013), “Okun’s law across the business cycle and during the Great Recession: a Markov switching analysis”, College of William and Mary Working Paper 139.

Valadkhani, A, and R Smyth (2015), “Switching and asymmetric behaviour of the Okun coefficient in the US: Evidence for the 1948–2015 period”, Economic Modelling 50: 281-290.