Once – maybe twice – in every generation, the global economy witnesses a protracted and widespread commodity boom. And in each boom:

- The common perception is that the world is quickly running out of key materials and economic growth will inexorably grind to a halt, bringing in its wake the prospect for interstate conflict (Moyo 2012).

And while many in the investment community acknowledge this as a possibility, they also suggest that in the meantime serious fortunes are to be made in riding the wave of ever increasing prices (Heap 2005, Rogers 2004).

- Economists, by contrast, counter such thinking as belied by the long-run history of real commodity prices, building on an extensive academic and policy literature chartering developments in the price of commodities relative to manufactured goods in particular (Grilli and Yang 1988, Harvey et al. 2010).

This side of the debate holds that the price signals generated in the wake of a global commodity boom are always sufficiently strong to induce a countervailing supply response as formerly dormant exploration and extraction activities take off and commodity prices moderate.

What is missing from this discussion is a consistent body of evidence on real commodity prices and a consistent methodology for characterising their long-run evolution.

New data on old prices

To that end, this Vox column introduces a new – and publicly available – dataset on real commodity prices over 164 years for 32 commodities. Individually, these series span a very wide range of commodities, being drawn from the animal products, energy products, grains, metals, minerals, precious metals, and soft commodities sectors. What is more, they collectively represent $8.26 trillion worth of production in 2011. Even accounting for potential double-counting and excluding potentially idiosyncratic sectors like energy, the sample constitutes a meaningful share of global economic activity.

Trends, cycles, and episodes in real commodity prices

One of my recent papers is related to this project and suggests and documents a comprehensive typology of real commodity prices from 1850 (Jacks 2013). In this typology, real commodity price series are comprised of long-run trends, medium-run cycles, and short-run boom/bust episodes. As such, there are a few key findings:

- Perceptions of the trajectory of real commodity prices over time are vitally influenced by how long a period is being considered and by how particular commodities are weighted when constructing generic commodity-price indices.

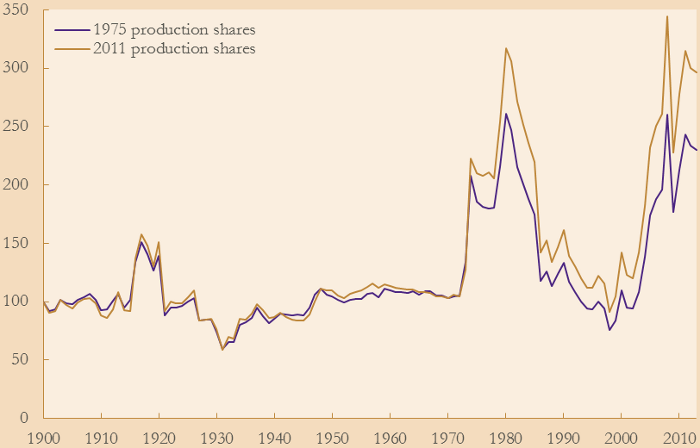

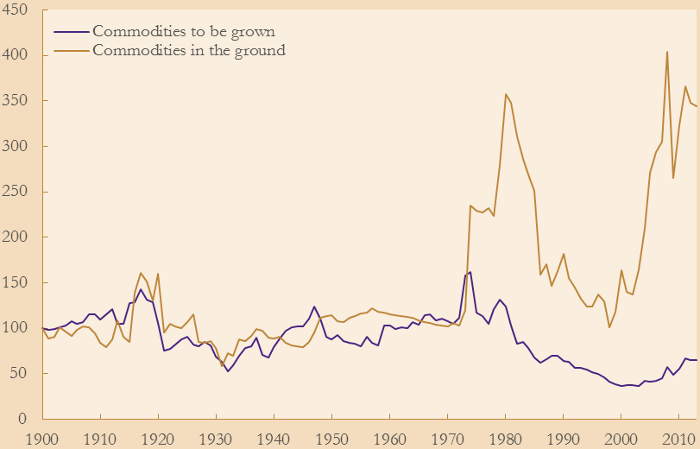

Applying weights drawn from the value of production in 2011, real commodity prices have increased by 244.69% from 1900, 177.59% from 1950, and 38.90% from 1975. Applying weights drawn from the value of production in 1975, real commodity prices have increased by 165.84% from 1900, 117.57% from 1950, and 10.80% from 1975. As seen in Figure 1, this suggests that much of the conventional wisdom on long-run trends in real commodity prices may be unduly ‘pessimistic’ about their prospects for future appreciation or unduly swayed by events either in the very distant or very recent past. Figure 2 also suggests a potentially large, but somewhat underappreciated distinction in between ‘commodities in the ground’ (energy products, metals, minerals, and precious metals), which have evidenced secular increases in real prices versus ‘commodities to be grown’ (animal products, grains, and soft commodities) which have evidenced secular declines in real prices.

Figure 1. Real commodity prices, 1900-2013 (1900=100)

Figure 2. Real commodity prices by type, 1900-2013 (1900=100)

- There is a consistent pattern of commodity price super-cycles which entail decades-long positive deviations from these long-run trends in both the past and present;

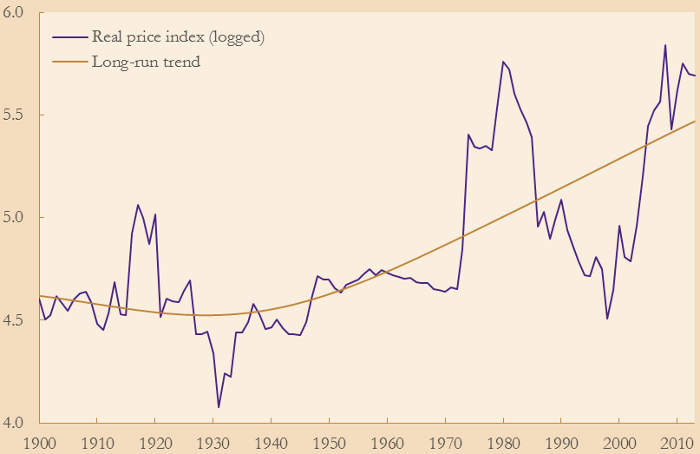

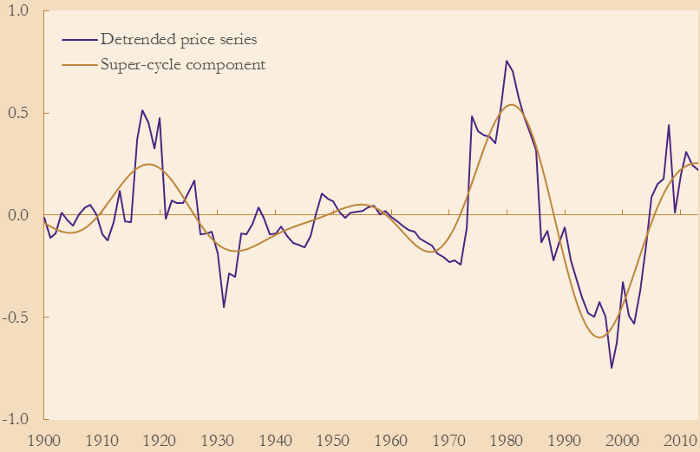

Commodity price super-cycles are thought of as broad-based, medium-run cycles corresponding to upswings in commodity prices of roughly 10 to 35 years (Cuddington and Jerrett 2008, Erten and Ocampo 2012). These are demand-driven episodes closely linked to historical episodes of mass industrialisation and urbanisation which interact with acute capacity constraints in many product categories – in particular, energy, metals, and minerals – in order to generate above-trend real commodity prices for years, if not decades on end. This phenomena is seen in Figures 3a and 3b which depict, in turn, the log of a real commodity price index, its long-run trend, and a super-cycle price component estimated off the detrended real price series.

Figure 3a. Real commodity price components, 1900-2013

Figure 3b. Real commodity price components, 1900-2013

Significantly, when considered in isolation, fully 16 of the sample’s 32 commodities are in the midst of super-cycles, evidencing above-trend real prices starting from 1994 to 1999. The common origin of these commodity price super-cycles in the late 1990s underlines an important theme of the paper: namely that much of the recent appreciation of real commodity prices simply represents a recovery from their multi-year – and in some instances, multi-decade – nadir around the year 2000. At the same time, the accumulated historical evidence on super-cycles suggests that the current super-cycles are likely at their peak and, thus, we are nearing the beginning of the end of above-trend real commodity prices.

- My paper also offers a consistently applied methodology for determining real commodity price booms and busts which punctuate – and help determine – the aforementioned commodity-price super-cycles.

These boom/bust episodes are found to be historically pervasive with a few clear patterns: periods of freely floating nominal exchange rates have historically been associated with longer and larger real commodity price boom/bust episodes with the last 40 years in particular having witnessed increasingly longer and larger real commodity price booms and busts than the past. This exercise also underlines another key output from this project in the form of long-run series on commodity-specific price booms and busts which may be of interest to researchers looking for plausibly exogenous shocks to domestic economies.

Conclusions

Cumulatively, these results suggest that policymakers and researchers alike should avoid two opposing temptations.

- First, policymakers should not confuse cycles for trends in real commodity prices;

Appropriate measures need to be devised and put in place which fundamentally recognise the boom/bust nature of global commodity markets and the attendant procyclicality this induces in both private investment and public revenues.

- Second, researchers – especially in the academic community – should be more aware of the fact that we do indeed live in a world of scarcity and that commodity-specific differences in supply and demand generate differential paths in real commodity prices, not only in the past but also presumably in the future.

References

Cuddington, JT and D Jerrett (2008), “Super Cycles in Real Metal Prices?” IMF Staff Papers 55(4), 541-56.

Erten, B and JA Ocampo (2012), “Super-cycles of Commodity Prices Since the Mid Nineteenth Century”, DESA Working Paper 110.

Grilli, ER and MC Yang (1988), “Primary Commodity Prices, Manufactured Goods Prices, and the Terms of Trade of Developing Countries: What the Long Run Shows”, World Bank Economic Review 2(1), 1-47.

Harvey, DI, NM Kellard, JB Madsen, and ME Wohar (2010), “The Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis: Four Centuries of Evidence”, Review of Economics and Statistics 92(2), 367-377.

Heap, A (2005), “China—The Engine of Commodities Super Cycle”, Citigroup Smith Barney.

Jacks, DS (2013), “From Boom to Bust: A Typology of Real Commodity Prices in the Long Run”, NBER Working Paper 18874.

Moyo, D (2012), Winner Take All, New York, Basic Books.

Rogers, J (2004), Hot Commodities: How Anyone Can Invest and Profit in the World’s Best Market, New York, Random House.