The period since WWII has been marked by growing economic and cultural globalisation and, in Europe, increasing political integration inside the EU. Brexit bucks this trend. It has ignited a debate about the future of the EU, and the extent to which further globalisation is inevitable. For example, after the Brexit vote, the European Commission issued a white paper laying out scenarios for the future of the EU. It included not only 'muddling through' and committing to closer integration, but also scaling back the EU to just the single market, or building a multi-speed Europe (European Commission 2017).

It is too soon to know whether Brexit will be merely a diversion on the path to greater integration, a sign globalisation has reached its limits, or the start of a new era of protectionism. In recent work, I attempt to shed light on the implications of Brexit by summarising the research so far on the likely economic consequences of Brexit, and discussing the evidence on why the UK voted to leave the EU( Sampson 2017).

The economic consequences of Brexit

Forecasting the economic consequences of Brexit is made difficult by the lack of a close historical precedent, and uncertainty over what form future relations between the UK and the EU will take. Facing this challenge, researchers have used three approaches to estimate the effects Brexit:

- Historical case studies of the economic consequences of joining the EU (Campos et al. 2014, Crafts 2016).

- Simulations of Brexit using computational general equilibrium trade models (Aichele and Felbermayr 2015, Ciuriak et al. 2015, Dhingra et al. 2017).

- Reduced-form evidence based on estimates of how EU membership affects trade, and how trade affects income per capita (Dhingra et al. 2017).

Each of these approaches has its limitations, but there has been a consensus that, in the long run, Brexit will make the UK poorer because it will create new barriers to trade, foreign direct investment, and immigration. It's less certain how large that effect will be. Plausible estimates range between 1% and 10% of the UK’s income per capita. Other EU countries are also likely to suffer from reduced trade, but their losses will probably be much smaller.

This uncertainty has two sources. First, different research strategies produce different results. Methods that attempt to capture the effect of Brexit on foreign direct investment and productivity growth report larger losses.

Second, the losses will depend on the terms under which the UK and EU trade following Brexit. Continued membership of the single market is the best option for the British and European economies. If the UK leaves the single market, research shows that to minimise the costs UK-EU negotiations should prioritise keeping non-tariff barriers low and ensuring market access in services, rather than purely focusing on tariffs. Less is known about the likely dynamics of the transition process, or the extent to which economic uncertainty and anticipation effects will affect economic activity before Brexit happens.

Who voted for Brexit?

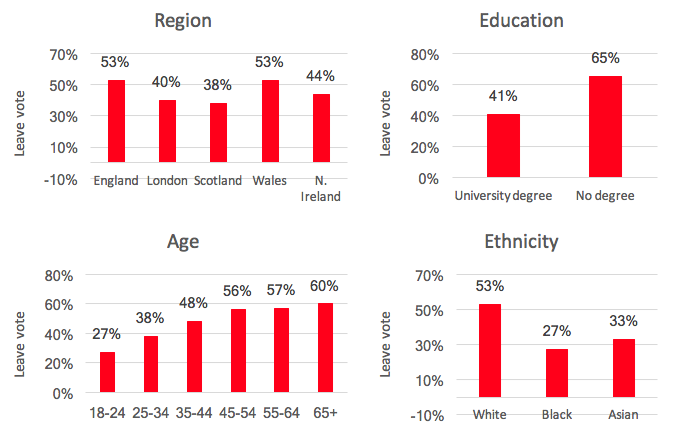

The referendum split the electorate on the basis of geography, age, education, and ethnicity. Figure 1 shows data on voting patterns. England and Wales voted to leave, while Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain. In England, support for Brexit was low in London, where only 40% voted to leave. Older and less-educated voters were more likely to vote leave, while large majorities of black and Asian voters supported remain. Voting to leave the EU was also strongly associated with holding socially conservative political beliefs, and thinking life in Britain is getting worse (Lord Ashcroft Polls 2016).

Econometric studies of voting outcomes by area (Goodwin and Heath 2016a, Becker, Fetzer, and Novy 2016, Colantone and Stanig 2016) and voting intentions at the individual level (Goodwin and Heath 2016b, Colantone and Stanig 2016) have established three main regularities:

- Education and age: These are the strongest demographic predictors of voting behaviour, with education stronger than age.

- Poor economic outcomes: At the individual or area level, these are associated with voting to leave, but economic variables account for less of the variation in the leave vote share than educational differences.

- Immigration: Support for leaving the EU is strongly associated with self-reported opposition to immigration, but a higher share of EU immigrants in the local population is actually associated with a reduction in the leave vote share. There is some evidence growth in immigration, particularly from the 12 predominantly eastern European countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007, is associated with a higher leave vote share, but the effect is small and not always present.

The picture painted by the voting data is that the Brexit campaign succeeded because it received the support of a coalition of voters who felt left behind in modern Britain. People may have felt left behind because of their education, age, economic situation or because of tensions between their values and the direction of social change, but, broadly speaking, a feeling of social and economic exclusion appears to have translated into support for Brexit.

Figure 1 Leave vote shares in Brexit referendum

Source: Regional data from the Electoral Commission; demographic data from Lord Ashcroft Polls (2016).

Why did the UK vote for Brexit?

Knowing that left-behind voters supported Brexit does not tell us why they voted for Brexit. We can immediately rule out one explanation - the vote was not the result of a rational assessment of the economic costs and benefits of Brexit. As discussed above, EU membership benefits the UK economy on aggregate, and there is no evidence that changes in either trade or immigration due to EU membership have had large enough distributional consequences to offset the aggregate benefits, and leave left-behind voters worse off. This leaves two plausible hypotheses for why the UK voted to leave.

- Primacy of the nation state. Successful democratic government requires the consent and participation of the governed. British people identify as citizens of the UK, not the EU. Consequently, they feel the UK should be governed as a sovereign nation state. According to this hypothesis, the UK voted to leave because Brexit supporters wanted to ‘take back control’ of their borders and their country.

- Scapegoating the EU. Many people feel left behind by modern Britain. Influenced by anti-EU sentiments as expressed in newspapers and by euro-sceptic politicians, they blame immigration and the EU for many of their problems. According to this hypothesis, voters supported Brexit because they believed EU membership increases their discontent with the status quo.

It is likely that both hypotheses played some role in the referendum outcome, but we do not know how much each contributed to it. When leave voters are asked to explain their vote, they talk about national sovereignty and immigration. But these responses are consistent with either hypothesis. They could reflect voters’ attachment to the UK as a nation state, or they may mirror the language used by pro-Brexit newspapers and politicians.

The 'nation-state' and 'scapegoating' hypotheses have different implications, however, for how policymakers should respond to Brexit, and for the future of European and global integration.

Brexit and the future of international integration

The nation-state hypothesis is closely related to Rodrik’s (2011) idea that nation states, democratic politics and deep international economic integration are mutually incompatible. From this perspective, the deep integration promoted by the EU, in particular free movement of labour and regulatory harmonisation, cannot coexist with national democracy. For Europe to remain democratic, either the people of Europe must develop a collective identity, or the supranational powers of the EU must be reduced. The nation-state hypothesis, however, does not directly threaten the sustainability of shallow integration agreements that aim to reduce tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. The UK government’s current approach to Brexit assumes the validity of the nation-state hypothesis (Fox 2016, May 2017).

The scapegoating hypothesis does not threaten the ideal of the EU as a supranational political project, or provide an immediate reason to reconsider the desirability of deep integration. But it does pose a different challenge to the future of international integration. As long as geography continues to be an important determinant of group identity, international institutions will always be more vulnerable to losing popular support than domestic institutions. Colantone and Stanig (2016) found that exposure to Chinese import competition had a positive effect on support for Brexit. This would be consistent with the scapegoating hypothesis.

If this hypothesis proves correct, policymakers seeking to promote European and global integration have two main options available. One would be to channel popular protests against another target. The other would be for policymakers to focus on tackling the underlying causes of discontent among left-behind voters. Addressing economic and social exclusion is a daunting challenge, but enacting policies that would support disadvantaged households and regions, and broaden access to higher education, would be an obvious starting point.

Responding to Brexit voters

Understanding and responding to the motivations of voters who oppose the EU will play an important role in determining whether the benefits of economic and political integration can be preserved. If British voters supported Brexit to reclaim sovereignty from the EU, then, provided they are willing to pay the economic price for leaving the single market, they will view Brexit as a success. But, if misinformation drove support for Brexit, then leaving the EU will not make them happier.

References

Aichele, R and G Felbermayr (2015), Costs and Benefits of a United Kingdom Exit from the European Union, Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Becker, S O, T Fetzer and D Novy (2017), “Who Voted for Brexit? A Comprehensive District-Level Analysis”, CEPR Discussion Paper 11954.

Campos, N F, F Coricelli and L Moretti (2014), “Economic Growth and Political Integration: Estimating the Benefits from Membership in the European Union Using the Synthetic Counterfactuals Method”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9968.

Ciuriak, D, J Xiao, N Ciuriak, A Dadkhah, D Lysenko and B Narayanan (2015), The Trade-related Impact of a UK Exit from the EU Single Market, Ciuriak Consulting Inc.

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2016b) “Global competition and Brexit”, BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper 2016-44, November.

Crafts, N (2016), “The Growth Effects of EU Membership for the UK: A Review of the Evidence”, University of Warwick mimeo.

Dhingra, S, H Huang, G Ottaviano, J P Pessoa, T Sampson and J Van Reenen (2017), “The Costs and Benefits of Leaving the EU: Trade Effects”, Economic Policy, forthcoming.

European Commission (2017), “White Paper on the Future of Europe: Reflections and Scenarios for the EU27 by 2025”.

Fox, L (2016) Liam Fox’s speech to the World Trade Organization, 1 December.

Goodwin, M and O Heath (2016a), “The 2016 Referendum, Brexit and the Left Behind: An Aggregate-level Analysis of the Result”, Political Quarterly 87: 323-332.

Goodwin, M and O Heath (2016b), “Brexit Vote Explained: Poverty, Low Skills and Lack of Opportunities”, Joseph Rowntree Foundation,

Lord Ashcroft Polls (2016), “How the United Kingdom Voted and Why”, 24 June.

May, T (2017), “The Government’s Negotiating Objectives for Exiting the EU”, Lancaster House speech, 17 January.

Rodrik, D (2011), The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. WW Norton & Company.

Sampson, T (2017), “Brexit: The Economics of International Disintegration”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, forthcoming.