Editor's note: This column first appeared as a chapter in the VoxEU eBook, What To Do With the UK? EU perspectives on Brexit, available to download here.

In many ways, the reasons behind the Brexit vote find many sympathisers in France: a rejection of the EU, which appears to many as a bureaucracy with higher administrative burdens than those of its member countries and which is incapable of delivering growth and employment; a lack of any perceived benefit from the Single Market; disapproval of the way the EU is handling the refugee crisis; an open space with no border controls which is prone to insecurity; and a desire to repatriate some legislative power. Even though Britain has always been less engaged in the European political project, French citizens share these frustrations. But the reasons for France’s disenchantment with Europe go beyond that. The French see the EU as an entity that is unable to cope with the perceived downside from globalisation – a place where competition is not fair and where institutions lack political oversight.

For these reasons, the French position on the Brexit negotiations will likely focus on the desire to preserve or increase France’s competitiveness, while seeking to attract businesses that could enhance its international position for trade in goods and services. On the freedom of movements, France’s position is more ambiguous. It will want to preserve the production chain, which for certain industries is intimately linked to the UK, but also to limit the movement of posted workers, a significant political issue in France. In addition, its own difficulties in coping with the issue of migration may play a role in the negotiations. Finally, France may trade some negotiating objectives against concessions by other EMU countries concerning social considerations and further integration such as a common budget, albeit small, although it is unlikely to be at the centre of the future discussions.

Despite a lack of competitiveness, bilateral economic ties are mostly in favour of France

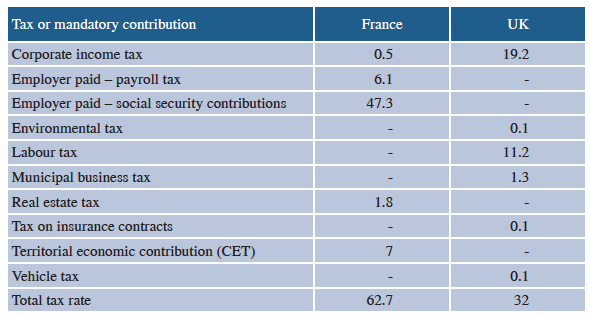

Whatever the competitiveness metric, France tends to perform poorly against the UK. The well-known Global Competitiveness Index from the World Economic Forum ranks countries based on various factors such as the reliability of institutions, infrastructure, education or innovation. In the 2015-2016 report, France is ranked 22nd overall and the UK 10th. France is behind the UK in almost all areas, but according to the WEF the gap is most significant when it comes to labour market efficiency (flexibility and use of talents) and technological readiness (adoption and diffusion of technology). On competitiveness, France is much lower than the UK, especially on corporate taxation. International firms are better off setting up shop in the UK. According to the World Bank Doing Business 2016, a firm pays much more tax when based in Paris than in London (see Table 1).

Table 1 Summary of tax receipts as a proportion of corporate profit for France and the UK

Source: Doing Business 2016, World Bank.

At the same time, the trade and investment ties between France and the UK are rather strong and mostly in favour of France. The UK is the 5th largest export market for France, representing 7.1% of its exports. It is also the 8th largest source country, representing 3.9% of French imports. The French market share in the UK is twice as high as its global market share. The UK accounts for the largest French bilateral trade surplus, with €12.1 billion in 2015 (0.5% of GDP). The French food and wine industry accounts for almost 25% of the total surplus. The rest of the trade relationship is mostly intra-industry trade focused on automobiles, car parts, pharmaceuticals, aircrafts and aerospace-related goods. France is also the 3rd largest foreign investor in the UK, with investments totalling around 4.8% of GDP in 2014. Conversely, British investment is important in France, at about 2% of GDP in 2014. The UK is the primary European country in which French firms operate, with 359,000 employees and 3,074 subsidiaries based there, and it is second only to Germany in terms of turnover at €113.2 billion in 2014. This large presence of French firms in the UK stems not only from the strong ties between the two countries, but also from the difference in tax policy mentioned above, currently reinforced by EU rules of exemption on withholding taxes on the payment of dividends and interest between parent and subsidiary.

As a result, France will pay particular attention to tax policy arrangements with the UK. It will want to prevent any further harm to its competitiveness. Any attempt by the UK to use taxation to compete with the EU runs the risk of creating tensions in the negotiations.1

London, the symbol of France’s battle against British exceptions and regulatory arbitrage

The UK has always promoted the concept of differentiated integration. It has not adopted the euro, it has wanted to limit the scope of the banking union, and it opted out of Schengen. Recently, the Parliament Treasury Select Committee has launched a survey on Solvency II, which could be interpreted as a sign that the UK wishes to use regulation to attract financial firms.

France will likely be opposed to granting access to EU facilities if it is perceived that there is ‘unfair competition’ on the grounds of tax or regulatory matters. It will oppose any measure that could allow regulatory or tax arbitrage for the British financial industry, of course, but also for any other sector where access to the Single Market will be granted. This could include, for example, regulation for utilities such as energy, the digital industry (France is particularly cautious on data privacy), and transportation. Conversely, France will likely try to attract financial services to Paris.

First, any opt-out from regulation while granting access to the financial Single Market for the UK would be seen as a retreat from the objective of harmonisation of financial regulations. In Paris’ view, a harmonised competition and regulatory framework is key for both market integrity and financial stability, which also benefits London. Second, during the last negotiations on supervision, the UK sought to limit European authorities’ oversight and sought a flexible regime for relationship with third parties. Yet, differences in the implementation of the single rule book would likely be viewed as a way of granting some advantage to the City. As such, France will consider that it is incompatible to both grant access to the continental financial market and to exempt the UK from full European supervision of the implementation of the single rule book. In the absence of a deal on supervision, France would emphasise that the euro is the ‘currency of the union’, question the principle of non-discrimination of currency, and could insist on repatriating clearing houses on the continent. Such a relocation would be considered essential for financial stability reasons, as the Eurosystem carries credit and liquidity risks related to trade clearance.

Conversely, France is already taking steps to attract those financial firms that would seek to leave London. As the number of French employees in the City has grown larger over the past decades, and brain flight is a significant political issue, the French authorities will likely try to attract firms that doubt that a good deal can be reached. Indeed, the French banking authority (ACPR) and financial market supervisor (AMF) have already taken measures to attract British financial firms.2 In order to simplify and speed-up procedures, both authorities are offering English-speaking contacts to guide UK-based applicants. They are also accepting documents in English that have already been submitted to the British supervisors. Beyond anecdotal evidence, there is no evidence that these steps have had any material impact so far, at least up until Theresa May announced when Article 50 would be triggered. In addition, France may wish to look at the regulatory framework for the Fintech industry, with a view to repatriating some of this activity to the continent.

The human puzzle: Calais migrants, French workers and UK pensioners

The issue of labour mobility is a complex one for France as it combines a lack of job opportunities for some workers (with lower or no qualifications) with more attractive wages and careers for qualified workers. Officially, nearly 150,000 French citizens live in the UK; including students, the number is closer to 300,000. The number of UK citizens living in France is also around 150,000. Among the French living the UK, 25-40 year-olds are the dominant group, while about a third of Britons living in France are over 65. Importantly, most French who work in the UK did not move for fiscal reasons – a typical 35-40 year-old household with two children ends up with the same level of taxation as in France, but with less social services. They move because job opportunities are more numerous and less dependent on initial educational background. France could have to cope with the return of these workers if they were denied the permission to stay in the UK. This situation has always been the Achilles’ heel of the political debate in France, especially because qualified French students are actively sought by the financial sector.

The issue of labour mobility is made even more complicated by two additional reasons. First is the question of migrants and refugees, which is equally sensitive in the UK. Second, the issue of posted workers has attracted significant attention in the public debate. France has no official objection to the freedom of movement, but it has recently objected to the growing use of posted workers. It received the 2nd highest number of posted workers in the EU in 2014.3 It considers that low-qualified European migrants compete directly with local workers for jobs in some sectors, such as construction and domestic services. In these sectors at least, France could be tempted to limit the freedom of movement. It would be highly regrettable if France were to use the Brexit negotiations to attempt to restrict the freedom of movements. However, since other countries could well support such an attempt, politicians might be tempted. It would be more helpful to review the Posted Workers Directive, with a view to introducing a fairer set-up for those workers that move around the EU on behalf of their firms. For example, posted workers working in France (or any other country) could be submitted to the same labour regulations, including the minimum wage and social contributions. This would restore the level playing field.

The small town of Calais has become an infamous symbol of migration, yet this has nothing to do with the EU. The Le Touquet agreement, which is pivotal to the UK’s immigration control framework, is built on the premise that the UK can better control migrants wishing to cross the Channel on French territory (and vice versa, although this is much less relevant). Given the sensitive political debate around refugees and immigration, France could be tempted to seize the opportunity of the Brexit negotiations to reopen this agreement, even if it is bilateral and not part of any EU Treaty.

Accounting for political considerations: French demands for more social EU support and possibly EU deepening

Unlike the UK, since the beginning of the EU, France has been pushing towards institutional integration, the promotion of a ‘European social model’, and further integration such as a common budget, albeit small. These discussions came to a halt with the French 2005 referendum that rejected the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty. In 2005, the country was nearly equally divided between those believing in ‘more Europe’ and those signalling that Europe was inefficient in addressing their concerns. Today populism and Euroscepticism is growing in France across the political spectrum, but much more vocally on its extremes.

Yet, a new government could decide to be more forceful in promoting both the European social model and deeper economic integration. France has constantly argued in favour of completing the banking union, but also supports a European budget to finance investment and a European unemployment insurance. In Paris’ view, Europe is currently very asymmetric, with more integration on the economic and banking side than on the budgetary and social sides.4 A union that is seen as caring more about the people could turn around public opinion and revive the European construction. Even though an ambitious federal budget will not be part of the Brexit negotiations, France could use these negotiations to press its demands, such as the completion of the banking union or an enlarged Juncker Plan. France and Germany have long disagreed on the macroeconomic framework. France wants more common budgetary measures, including the issuance of debt to support investment. It also seeks more flexibility in the fiscal rules to deal with low growth. German puts more emphasis on structural reforms and debt restructuring, and is highly reluctant to consider any form of debt mutualisation. It would probably not be a good negotiating strategy to mix Brexit and EU discussions, but Brexit should lead to a redefinition of the EU project, including the Eurozone.

Conclusion: Expect a hard stance towards the UK in some sectors

France is likely to seek to include the UK in a comprehensive free trade zone to maintain easy access to the UK markets, but with a view to safeguarding its own competitiveness. This is particularly challenging as France would likely suffer most, in the short term, from a hard stance in the negotiations. Yet, the French authorities will be particularly mindful of tax competition, freedom of movement, as well as financial regulation and supervision in order to avoid fiscal, social and regulatory dumping. As the UK is likely to stand firm on immigration control and financial supervision, the negotiations with France will presumably be difficult.

Endnotes

[1] Financial Times, “France hits out at UK plan to cut corporate tax”, 11 July 2016.

[2] “The ACPR and the AMF are simplifying and speeding up licensing procedures in the context of BREXIT”, press release, 29 September 2016.

[3] See http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=15194&langId=en.

[4] Le Journal du Dimanche, “François Hollande: ‘Ce qui nous menace, ce n’est pas l’excès d’Europe, mais son insuffisance’”, 19 July 2015.