Economists’ opinions on Brexit are often dismissed as politically biased or driven by groupthink. While these charges are overstated, it is legitimate to point out that assessments of the impact of Brexit that focus narrowly on its impact on GDP miss broader economic and social concerns – for example, inequality and regional disparities (e.g. Whitaker 2018) – as well as explicitly political issues, in particular sovereignty. In early 2017, therefore, academics at the UK in a Changing Europe – some of us, but no means all, economists – set out four ‘tests’ for Brexit (UK in a Changing Europe 2017) that attempted to take account of that wider context while setting out some objective criteria by which the success of Brexit could be judged.

We argued that the referendum campaign had revealed some key themes and issues that underlay the British political debate. Our tests, therefore, reflected this broad consensus. They were the following:

- The economy and the public finances: Would Brexit make the country better off?

- Fairness: Would Brexit help some of those individuals and communities who have not benefited from growth over the past 30 years?

- Openness: The UK has a long and well-established consensus, across the political spectrum, in favour of free trade and open markets as a means to greater prosperity. Would this openness continue, and even go further?

- Control: Would Brexit enhance the democratic control the British people exercise over their own economic destiny?

We deliberately chose not to frame the tests around the key issues that are the subject of the negotiations between the UK and the EU over the terms of our withdrawal and our future relationship.

Of course, the UK has not left the EU yet, and there is a plausible chance that it may not do so. Nevertheless, Brexit is a process, not an event. Three years on from the referendum, it seems like a good time to take stock. Has the Brexit process, so far, been good or bad for the UK, and what can we say about its likely future impacts on each of the ‘tests’ described above?

The economy and the public finances

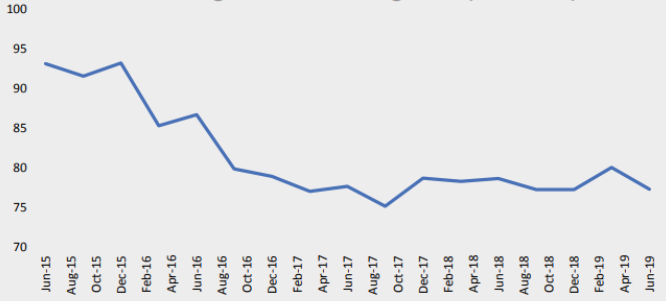

There is little doubt that the impact of the Brexit vote on the UK economy has been negative (Springford 2018). The sharp fall in sterling pushed up prices without doing much to boost exports, and uncertainty has reduced business investment (Crowley et al. 2019, Breinlich et al. 2019). The UK is clearly poorer as a result. Both growth and tax revenue appear lower than they might otherwise have been, although the labour market has remained resilient. Nor is there much sign of any reduction in macroeconomic imbalances. While far from disastrous, and far from the apocalyptic predictions of some in the Remain campaign, the overall direction is clear.

Figure 1 Sterling effective exchange rate (2005=100)

Source: Bank of England

A Brexit deal would reduce uncertainty and strengthen the pound, and it might result in a short-term boost to growth. But the overwhelming consensus among economists, both independent and within government, remains that leaving the Single Market, as envisaged under the current Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration, will have a significant and negative impact on UK trade with the EU (Department for Exiting the EU 2018). The impact of a no deal Brexit – even leaving aside the unquantifiable potential short-term disruption to trade and the wider economy – would be even greater (UK in a Changing Europe 2018). Nor, given the current geopolitical environment and US trade policy, does it seem plausible that trade deals with third countries will provide much compensation (Department for Exiting the EU 2018). Even if the UK were to reverse course and remain in the EU, there would still be some lasting damage to our international reputation for political and economic stability. While huge uncertainties remain about the long-term economic impacts of Brexit, it seems highly unlikely to be positive. The question is how large the damage will be.

Fairness

Pressures on public services, in particular social care, education and policing, have intensified. While Brexit is not the main driver here, it has certainly not helped (Office for Budget Responsibility 2018). Cuts to benefits mean that inequality and child poverty are rising, albeit only marginally, mitigated to some extent by large rises in the National Minimum Wage (Department for Work and Pensions 2019).

Although real wage growth has recovered somewhat, there is little evidence that reduced EU migration is boosting pay growth at the bottom end. More broadly, there is no sign of substantial new policies to address the ‘left behind’ areas and communities that some argue drove the Brexit vote. Indeed, the preoccupation of the government, media, and political system with Brexit has meant that policy development in areas from social care to regional policy has largely stalled.

There is little prospect of this changing in the short to medium term. Most forms of Brexit will worsen the government’s fiscal position, probably significantly, reducing the space for new policy initiatives. Furthermore, the planned Spending Review is likely to be postponed. Although this is highly uncertain, the impacts of Brexit on regions and sectors are, if anything, likely to disadvantage those which are already lagging behind, although it is possible that targeted migration policy – joined up with continued rises in the National Minimum Age and action on education and skills – might over the medium term help the lower paid and less skilled.

Openness

The UK remains a relatively open economy. Indeed, the conclusion and implementation of further EU free trade deals has led to some modest further liberalisation, while there has been some relaxation of restrictions on non-EU immigration. However, perceptions have changed, and not for the better. This has had a clear real-world effect. The UK has certainly become a less attractive and welcoming destination for potential EU migrants, and the evidence suggests that Brexit has reduced both trade (REF) and investment flows (Serwicka and Tamberi 2018).

It is possible that in theory these impacts are temporary and could be reversed by post-Brexit policy choices. In particular, both the public and policy debate on immigration have turned in a more positive direction, and it looks at least plausible that, whatever happens on Brexit, the UK will choose a relatively liberal approach. On trade, and perhaps investment, however, the nature of the trade-offs means that it will be difficult if not impossible to reduce barriers with third countries without erecting them with the EU. Given the uncertainties over future policy, the prognosis is mixed.

Control

In a legal sense, as long as the UK remains an EU member, there is no sense in which either Parliament or the people have ‘taken back control’. Indeed, to the extent that the UK is marginalised or irrelevant in EU decision making, we have arguably lost control to some extent. Meanwhile, efforts to devolve decision making within the UK have stalled. Public perceptions reflect this.

However, this is perhaps the inevitable result of the Brexit process. While it is simplistic to suggest that on Brexit Day (or even after the end of the transition period) there will be a sudden shift, over time the UK will increasingly reclaim the ability to set its own policies – subject to the economic and political constraints faced by all countries – on trade, investment, and regulation. Translating that into a sense among the broader public that they have genuinely increased their own agency over decisions that shape their lives will, however, remain a challenge.

Conclusion

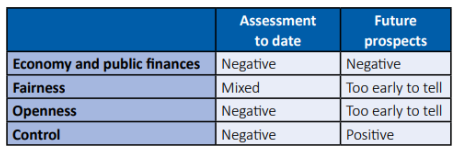

Our conclusions are summarised in the following table.

Our verdict on the impact of the Brexit process so far is unsurprising and unequivocal. While the apocalyptic predictions of the Remain campaign have failed to materialise, the economic damage has nevertheless been significant: not just a one-off inflation shock, but also more persistent impacts on investment, trade and migration, meaning the UK is already a somewhat less open economy. Nor is the UK, in any measurable sense, a fairer society. However, the seismic political impact of Brexit means that the UK has paradoxically lost control, at least temporarily, over some aspects of our economic future.

But these are early days, to say the least. Our judgement on the future prospects for Brexit is therefore necessarily more tentative. We can say with some degree of assurance, based on the consensus amongst credible economists, that Brexit will, overall, be negative for the UK economy and public finances. Indeed, that consensus has if anything been strengthened by developments so far, as the prospect of any Brexit that retains Single Market membership and free movement appears farther away than ever.

Correspondingly, however, this means that the UK will indeed have considerably more control over a range of policies – trade, regulation, and migration – than at present. The challenge of how to translate that gain in notional sovereignty into a genuine sense amongst the electorate that they have a real say will be central to British politics after Brexit. And the most difficult and uncertain issue remains what future governments will do to address the underlying discontent that, at least in part, drove the Brexit vote.

References

Breinlich, H, Leromian, E, Novy, D and T Sampson (2019), “Voting with their feet –Brexit and outward investment by UK firms”, CEP Brexit Analysis 13.

Crowley, M, O Exton and L Han (2019), “Renegotiation of Trade Agreements and Firm Exporting Decisions: Evidence from the Impact of Brexit on UK Exports,” CEPR Discussion Paper 13446.

Department for Exiting the EU (2018), EU exit: long-term economic analysis.

Department for Work and Pensions (2019), "Households Below Average Income".

Office for Budget Responsibility (2018), "Brexit and the OBR’s forecasts".

Serwicka, I and N Tamberi (2018), “Not backing Britain: FDI inflows since the Brexit referendum”, UK Trade Policy Observatory Briefing Paper 23.

Springford, J (2018), “The cost of Brexit to December 2018: towards relative decline?”, Centre for European Reform Insight, 30 March.

UK in a Changing Europe (2017), A successful Brexit: four economic tests.

UK in a Changing Europe (2018), Cost of no deal revisited.

Whitaker, M (2018), “Dis-united Britain: Inequality, Growth and the Brexit Divide”, Resolution Foundation, 25 May.