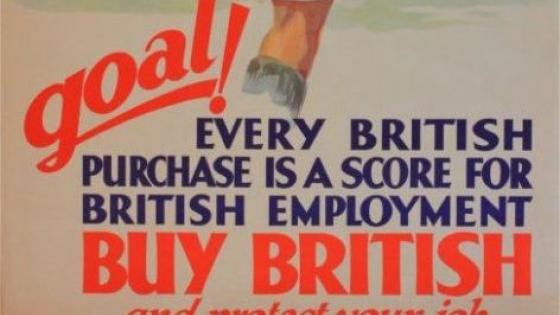

Exhortations to “buy national” occur in times of economic turmoil in an attempt to protect domestic industry and jobs (Higgins 2018: 249-284). For example, “Buy British” was pronounced during the 1930s – the same decade in which the US legislated “Buy American” (Trentmann 2008, Frank 1999). In the 1980s, similar initiatives were launched in Australia and New Zealand (Fenwick and Wright 2000, Fischer and Byron 1997).

Currently, there are suggestions that the UK government will require that components originating in Japan or South Korea and used in the UK assembly of cars be stamped “Made in Britain” to ameliorate the impact of higher EU tariffs after the post-Brexit transition phase.1 In this column, which draws on historical case evidence (Clayton and Higgins 2020), we question the viability of such a nationalist commercial policy.

Our focus is on the attempts by successive UK governments between the 1970s and early 1980s to initiate a “Buy British” policy. During this period, which coincided with the first decade following the UK’s accession to the European Economic Community (EEC), import penetration increased from 21% to 30% between 1973 and 1980 (Williams et al. 1983: Table 4, p. 119). Although UK exports to the EEC increased by a factor of 2.4 between 1967 and 1985, UK imports from the EEC increased by a factor of 3.3 during the same period (calculated from Tomlinson 2004: 195).

In other words, the phased application of the EEC common external tariff exacerbated the problem of “leakages” by exposing UK producers to duty free imports from other member states. Import substitution became a key aim of government policy to deal with a much more competitive environment brought about by the UK’s entry into Europe.

But, because the UK belonged to the EEC, it was legally bound to ensure that its domestic policies were consonant with the stipulations of the Treaty of Rome (1957). The free movement of goods was one such stipulation that governed the elimination of tariffs as well as restrictions having “equivalent effect”.

The latter are usually referred to as non-tariff barriers and include, for example, cumbersome Customs procedures for importers and “buy national” campaigns. Using evidence from the National Archives, we examined official discussions on the merits of using the non-tariff barrier – “Buy British” – to facilitate import substitution during the 1970s and early 1980s.

“Buy British” as a non-tariff barrier

In the context of the EU, there is limited literature on “buy national”, and that which exists has been dominated by legal scholars for whom this topic is but a subset of the much larger theme of quantitative restrictions having equivalent effect (Barnard 2013: 84-85). Although a substantial debate is in progress about the EU’s competition policy (e.g. Warlouzet 2018), the role of “buy national” as an import substitution policy (by limiting foreign competition in domestic markets) remains under-researched.

To the best of our knowledge, there is little informed literature on “Buy British” as a non-tariff barrier during the 1970s and 1980s, though a notable exception is Richard Thackeray (2019: 142-189). This omission is surprising because consumer expenditure was by far the biggest component of UK national income.

For any “buy national” campaign to succeed, two conditions have to be fulfilled. First, domestic consumers need to have a latent preference for domestic products, which can only be determined via consumer surveys. But because the UK was an EEC member state the government was prohibited from officially encouraging domestic consumers to buy British products. No such restrictions applied to private initiatives, but it was costly for individual industries or firms to conduct market research on whether a British mark (such as a flag or a “made in” mark) might increase their sales.

Second, consumers need to be able to differentiate domestic products from imports. This was the most vexatious of issues because it required a definition of “British”. For example, were the products of multinational companies operating in the UK “British”? Similarly, how should a manufacturer using mainly imported components label the finished product? There was also a problem of enforcement to be resolved: how would trade associations, customs authorities and the courts define a product as “British”?

Our evidence demonstrates that the Labour government of 1974-1979 recognised that a “Buy British” policy could facilitate an import substitution policy, but it sensibly decided against such a campaign on economic grounds. Conversely, the Conservative administration of 1979-1983 used consumer confusion as a pretext for launching “Buy British”, but even this scheme was abandoned after three years for legal reasons.

Reappraising “Buy British”

Why did the Labour government refuse to countenance the launch of a “Buy British” policy in the late 1970s, despite its possible import-saving potential? Until 1978, hard evidence on consumer preferences towards domestic and imported manufactures did not exist, and so the government commissioned a confidential consumer survey from Marplan.

The main findings of the Marplan survey were that country of origin had a negligible impact on consumer purchases of shoes, carpets, DIY/garden tools, and clothes, kitchen units and furniture. For domestic electrical appliances, survey respondents placed more emphasis on company brand than country of origin. While 50% of respondents indicated they always made an effort to buy British, or preferred to buy British, this was almost exactly offset by the 48% of respondents who claimed they were indifferent between domestic and foreign products, had no preference for buying British, or preferred not to buy British.

Overall, price and value for money were the best predictors of what products consumers would buy; country of origin was of negligible importance. These findings rightly convinced the Labour government that “Buy British” was not a viable solution to rising imports. Indeed, concerns were raised that efforts to promote “Buy British” might backfire by highlighting the relative inferiority of domestic products, especially in terms of “style” and “quality”. What was actually needed were more profound structural changes to improve the performance of British manufacturing.

The Conservative government approached the problem of import substitution from a different perspective. The Marplan survey, plus two new surveys commissioned from the National Consumers Council and the National Union of Townswomen’s Guilds, convinced the government on two matters: first, that consumers wanted to know about country of origin – in order to exercise a preference for domestic products; second, that in the absence of compulsory indications of origin, and ambiguous labelling, consumers were confused and even purchased imported products believing them to be British.

In 1982, the Conservative government therefore enacted legislation that required that domestic and imported clothing/textiles and footwear, cutlery, and domestic electrical appliances be marked with a conspicuous indication of geographic origin. Within three years, this protectionist scheme was declared illegal by the European Court of Justice because it acted as a non-tariff barrier (Commission v. United Kingdom, Case 207/83, 25 April 1985).

Conclusions

Our case study of “Buy British” during the 1970s and early 1980s addresses a number of themes that have considerable relevance today.

First, after the end of the transition period to manage the UK’s exit from the EU, the government will enjoy greater legal freedom to promote “Buy British”. But how likely is it that a new survey into UK consumer preferences for British or imported goods would reveal any fundamental change from those reported by Marplan in the 1970s? Our best guess is that price and robust quality indicators (such as durability and energy efficiency) will trump nativism. Consequently, unless and until UK manufacturers as a whole can achieve parity with international standards, import penetration will continue.

Second, accelerating globalisation and the rapid growth of imports in intermediate products for assembly into ‘British’ goods raise significant problems in defining a ‘national’ product. In this situation, how reliable will any country of origin mark be?

Customs authorities, for example, have long used a standard ‘substantial transformation’ test to assess whether imported products become ‘domestic’ if they undergo sufficient treatment in the importing country. Due to Brexit, UK customs will have to extend significantly the range of products tested. If strictly applied, this gold-standard test could disqualify many goods manufactured in the UK from being labelled “Made in Britain”.

If a lower standard for ‘British-made’ goods is applied, then who decides on this ‘standard’, and how it should be tested? Our study shows that there were substantial differences of opinion within and between manufacturing industries that prevented a workable definition. Even the strong Conservative government of the 1980s could not define “Made in Britain” even for a relative narrow range of manufactured goods.

Today, the growth of tradable services (such as insurance, education and healthcare) presents an even more intractable problem. Only powerful business lobbyists and lawyers would gain from attempts to turn “Buy British” from a slogan into a coherent and enforceable government commercial policy.

References

Barnard, C (2013), The Substantive Law of the EU, Oxford.

Clayton, D and D M Higgins (2020), ""Buy British": An Analysis of UK Attempts to Turn a Slogan into Government Policy, in the 1970s and 1980s”, Business History, 8 June.

Fenwick, G D and C I Wright (2000), “Effect of a buy national campaign on member firm performance”, Journal of Business Research 47: 135-145.

Fischer, W C and P Byron (1997), “Buy Australian Made”, Journal of Consumer Policy 20: 89-97.

Frank, D (1999), Buy American: The Untold Story of Economic Nationalism, Boston, MA.

Higgins, D M (2018), Brands, Geographical Origin and the Global Economy, Cambridge.

Thackeray, D (2019), Forging a British World of Trade, Oxford.

Tomlinson, J (2004), “Economic Policy”, in R Floud and P Johnson (eds), The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, vol. III. Cambridge, pp. 189-212.

Trentmann, F (2008), Free Trade Nation, Oxford.

Warlouzet, L (2018), Governing Europe in a Globalizing World, Abingdon.

Williams, K, J Williams and D Thomas (1983), Why are the British Bad at Manufacturing?, London.

Endnotes

1 See https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/car-industry-boris-johnson-made-britain-japan-south-korea-brexit-a9598466.html