Europe's longstanding productivity gap with the US has been the source of much debate among economists and policy-makers. It was the motivation behind the European Council's ‘Lisbon strategy’ of 2000, which aimed to close the EU-US productivity gap by 2010, a target that now looks unreachable.

But why has European productivity lagged behind the US for more than half a century? Various factors have been suggested and investigated, such as lower levels of investment in innovation and training, and the parlous state of the higher education sector in Europe. These almost certainly play a role. But they do not appear to explain the full size or persistence of the EU-US productivity gap.

Many business people have long harboured a suspicion that the ‘missing factor’ in explaining this gap is inferior European management practices. This has a long historical pedigree, with the Harvard business historians Alfred Chandler and David Landes both claiming that poor management practices held back European companies. In fact in 1947, as part of the Marshall Aid scheme to revive post-war Europe, American businessmen and engineers toured Europe to try and work out how to improve Europe's productivity, which had been lagging behind the US even before World War II. They concluded that ‘efficient management was the most significant factor in the American advantage’.

Economists have had relatively little to say about the role of management in driving productivity and other key performance indicators. This is largely because there has been an absence of good quality data on management practices. At the Centre for Economic Performance, we have been carrying out a large research project (with McKinsey & Company) that attempts to fill this void.[1] We have used a new survey approach to measure management practices in a systematic way in more than 4,000 manufacturing firms across Europe, the US and Asia.

By matching these data with information from firm accounts, we are able to explore in detail the relationship between management practices, the economic environment and the company’s performance. Overall, we find compelling evidence that better management practices are significantly associated with higher productivity and other indicators of corporate performance, including return on capital employed, sales per employee, sales growth and growth in market share. This is true in every country we look at, suggesting that our characterisation of good management practice is not intrinsically biased towards Anglo-Saxon approaches.

Across the whole sample, a conservative estimate indicates that differences in management practices account for a significant proportion – 10-30% – of the differences in productivity between firms and between countries. Why is there such variation in the management practices and productivity of competing companies? Our research offers some potential explanations for these differences and possible areas for policy interventions to encourage the uptake of good management practices.

Measuring management practices

Measuring management requires codifying the concept of good and bad management into a measure applicable to different firms within the manufacturing sector. We used an interview-based management practice evaluation tool that defines and scores from 1 (worst practice) to 5 (best practice) across 18 of the key management practices that appear to matter to industrial firms based on McKinsey’s expertise in working with thousands of companies across several decades. The 18 practices fall into four broad areas:

[2]

- Shopfloor operations: have companies adopted both the letter and the spirit of lean manufacturing?

- Performance monitoring: how well do companies track what goes on inside their firms?

- Target setting: do companies set the right targets, track the right outcomes and take appropriate action if the two don’t tally?

- Incentive setting: are companies hiring, developing and keeping the right people (rather than people they could do without) and providing them with incentives to succeed?

For each company in the study, researchers interviewed one or two senior plant-level managers, who knew only that they were taking part in a ‘research’ project. These managers were selected because they are senior enough to have a reasonable perspective on what happens in a company but not so senior that they might be out of touch with the shopfloor. The interviews relied on open questions and the interviewers were trained to probe for details of practices on the ground.

Management practices across countries

We find significant differences in management performance across countries. The US is at the top of the table, while Greece, India and China are the joint worst performers. Germany, Sweden and Japan are (not surprisingly) strong performers given the manufacturing focus of the survey, while France, Italy and the UK are all solidly mid-table.

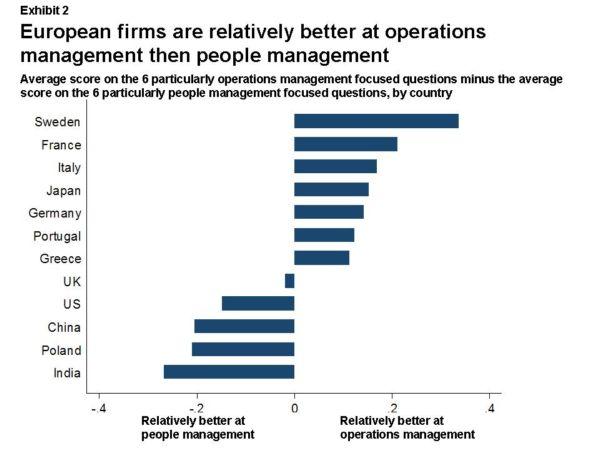

But the US is not entirely dominant. US firms score particularly highly for people management (such as promoting and rewarding talented workers quickly), but in shopfloor operations management, Sweden, France, Italy, Japan and Germany do relatively better.

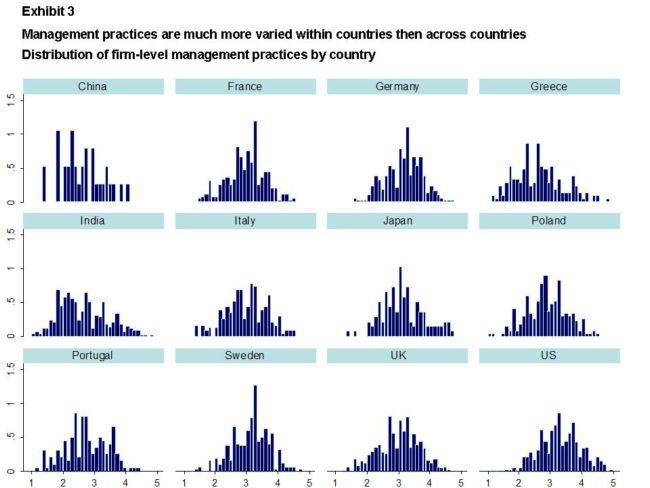

Overall, cross-country differences account for only 9% of the difference in management practice. Performance differences between companies in the same country are far larger than any cross-country variation. There is substantial overlap between countries. For example, the best 35% of firms in China and India perform better than the average European firm.

Managers are very poor at self-assessment

Good management appears to be so strongly linked with good performance that it seems reasonable to expect all firms to make better practices a priority. The techniques of good practice are, after all, available in the public domain in a wide range of easily accessible forms. Yet many firms are still poorly managed.

To examine possible causes of this disconnect, we asked managers as a final question in the interview to assess the overall management performance of their firm on a scale of 1 to 5. To avoid false modesty they were asked to exclude their personal performance from the calculation.

Interviewees’ answers to this question are not well correlated with either our management practice score or their own business performance. This applies in all countries, and does not change in better or more poorly managed firms.

At the country level we find Greek, Portuguese and Indian managers to be the most over-optimistic about their management practices, while the Japanese, Swedish and French managers are the least.

Government policy plays an important role

A variety of policy factors have an effect on companies’ adoption of good management practices. Most significant among these are their competitive environment and the flexibility of the local labour market.

Companies in the survey were asked to estimate the number of competitors operating in their market. The more competitors a company reported, the higher its management practice scores. This could be a result of two effects: first, good practice spreads quickly in highly competitive environments; and second, poor practice is eliminated by natural selection as poorer performing companies are removed from the marketplace.

We also find that flexible labour markets matter, since these appear to allow companies to adopt better people management practices. Companies operating in countries with more flexible labour market policies (measured using the World Bank’s index of employment law rigidity) score significantly higher in the evaluation of their people management practices. The US, with its extremely flexible employment laws, has by far the best people management record, a factor that contributes strongly to its overall top position among surveyed companies.

Ownership and skills

Firm ownership and the availability of skilled people, both in management and among the workforce in general, are also associated with important differences between the better-managed firms and the rest.

For example, multinational companies are well managed around the globe, managing to achieve extremely good management practices in countries like Greece, India and China despite the poor management practices of local domestic firms.

Family ownership and the traditional practice of primogeniture – handing down the CEO position to the eldest son – are associated with particularly bad management practices. This appears to be an issue for Europe since in the UK, France, Italy, Portugal and Greece around 10% of the manufacturing firms are family-owned with a CEO they claim has been chosen because they are the eldest son. The US performs much better on this dimension, with only 2% of its firms being family-owned with the CEO chosen because he is the eldest son.

The skills of both the managers and non-managers in the firm also appear to play an important role. For example, 84% of managers in the highest scoring firms are educated to degree level or higher, as are a quarter of the non-management work force. Among the lowest scoring firms, by contrast, only 54% of managers and 5% of the wider workforce have degrees.

How can Europe close the management gap with the US?

Our research shows a management gap between most European countries and the US. This is a situation that European governments can modify by encouraging the uptake of good management behaviour.

Our research suggests that strong competition and open labour markets both lead directly to improved management performance. Multinational companies have a strong positive effect too, and their influence is felt throughout the countries in which they operate.

Relentless improvement in educational standards is also likely to play a major role. Better-managed firms need more highly skilled workers and they make better use of them, while better-educated managers will be a key component of the performance transformation that both established and emerging economies must undertake if they are to maintain and improve their global competitive position.

This research was funded by the Advanced Institute of Management Research, The Anglo German Foundation, the Economic and Social Research Council, and the Kauffman Foundation.

[2] For full details of the survey methodology, including all the questions, see Bloom and Van Reenen (2006), ‘Measuring and Explaining Management Practices across Firms and Nations’, Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper No. 716 and forthcoming in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp0716.pdf