In the wake of the global crisis, academics and policymakers are questioning the relative merits of export-led growth strategies. Some have argued that many of the conditions responsible for that model’s success are no longer in place. Many developing countries have relied on an undervalued real exchange rate to boost their exports. But global economic prospects are weaker than in the past, and there is greater uncertainty about the advanced economies’ capacity to continue absorbing developing countries’ exports. Moreover a strategy of export-led growth paired with managed undervaluation is likely to incur costs if the real exchange rate is kept too low for too long. But how effective has real devaluation been in boosting exports and growth, and is it sustainable?

Can the real exchange rate play a role in boosting economic growth in developing countries?

In most developing countries the real exchange rate is manipulated to various degrees and is largely determined by economic policies rather than market fluctuations. Governments have a variety of policy instruments available to achieve a competitive real exchange rate, and, potentially, real undervaluation. Examples include a moderate fiscal consolidation in the presence of a low level of private absorption; the introduction of capital controls on capital inflows and the liberalisation of capital outflows; targeted interventions on foreign exchange markets; and a nominal depreciation associated with anti-inflationary policies such as price and wage moderation.

Empirical evidence shows that real exchange rate variations can indeed affect growth outcomes. Rodrik (2009) argues that real undervaluation promotes economic growth, increases the profitability of the tradable sector, and leads to an expansion of the share of tradables in domestic value added. The expansion of the tradable sector, which is harmed by institutional weaknesses and market distortions more than the non-tradable sector, promotes economic growth. Levy-Yeyati and Sturzzenegger (2007) show that an undervalued real exchange rate boosts output and productivity growth through an increase in savings and capital accumulation. Korinek and Serven (2010) claim that real exchange rate undervaluation can raise growth through learning-by-doing externalities in the tradable sector, which are sub-optimally produced in the absence of policy intervention.

Real exchange rate undervaluation, economic growth and export expansion

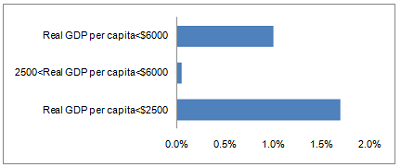

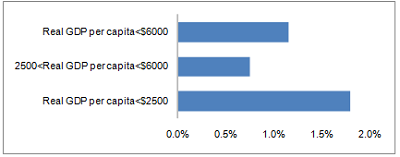

Closely following Rodrik (2009) and using the Penn World Tables 6.3 data (Heston, Summers and Aten 2009), we provide further evidence on the links between the real exchange rate, economic growth and export expansion (Haddad and Pancaro 2010). Real undervaluation has a positive effect on economic growth and on export expansion, but this effect is significant only for countries with per capita income below $2,500.

Figure 1: Impact of 50% Real Undervaluation on Real GDP per Capita Growth per Annum1

Figure 2: Impact of 50% Real Undervaluation on Exports to GDP Ratio per Annum2

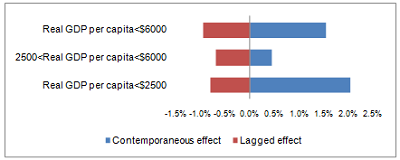

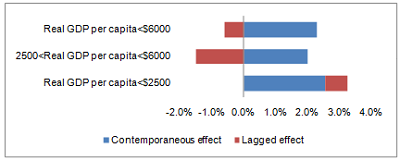

In the long run, the effect of a real exchange rate undervaluation on economic growth becomes negative; and on exports it becomes insignificant. In developing countries with per capita income below $2,500, real undervaluation has a positive contemporaneous effect on growth but a negative lagged effect. In developing countries with per capita income lower than $6,000 and higher than $2,500, real undervaluation has an insignificant contemporaneous effect and a negative lagged effect on growth. Real undervaluation has only a positive contemporaneous effect on exports; its lagged effect on export is insignificant for all income levels.

Figure 3: Impact of 50% Real Undervaluation on Real per Capita GDP Growth per Annum3

Figure 4: Impact of 50% Real Undervaluation on Exports to GDP ratio per Annum4

Real exchange rate variability, economic growth, and export expansion

An unstable real exchange rate causes more volatile relative prices, creates uncertainty, increases risk, and shortens investment horizons. Frequent movements in exchange rate expectations cause interest rate volatility and financial instability.

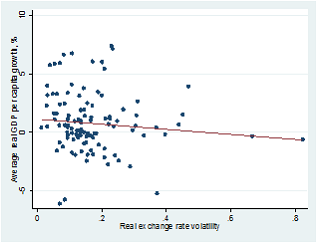

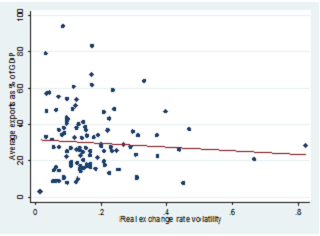

We provide evidence on the existence of a significant negative relationship between real exchange rate volatility and real per capita GDP growth. Furthermore, our evidence confirms the existence of a significant negative relationship between real exchange rate variability and the export/GDP ratio. However, this relationship is no longer significant when observations with extremely high real exchange rate volatility are dropped. Therefore, only large real exchange rate variability matters for exports.

Figure 5: Impact of Real Exchange Rate Variability on Real GDP per Capita Growth5

Figure 6: Impact of Real Exchange Rate Variability on Exports to GDP Ratio6

Is it sustainable to maintain an undervalued real exchange rate over time?

A stable and undervalued real exchange rate can be a key element in promoting economic growth; but maintaining this policy for too long may have significant adverse consequences.

First, such a policy may cause an excessive accumulation of low-yielding foreign reserves, which is inefficient. The return produced by foreign reserves is lower than the return produced by the same amount of wealth invested either in infrastructure or in a well diversified portfolio in international financial markets.

Second, a real undervaluation led by nominal depreciation and not associated with anti-inflationary policies such as price and wage moderation can cause high and destabilising liquidity growth and inflation.

Third, an undervalued real exchange rate can constrain monetary policy, which would no longer be free to target domestic objectives. This can cause an artificial process of overlending and overinvestment mainly in presence of an open capital account. The result can be an overheating economy.

Fourth, maintaining an undervalued real exchange rate for a long period of time may reduce the incentives to create a more developed financial sector.

Fifth, an artificial undervaluation of the real exchange rate is akin to a subsidy to firms which produce tradable goods. The subsidy is paid for by an implicit tax on consumers, who consequently have reduced purchasing power.

Finally, it may be difficult to exit a policy of sustained undervaluation once it becomes necessary. Governments may be pressured by influential lobbies (i.e. tradable goods producers) that derive rents from the status quo.

A stable and undervalued real exchange rate is a key step in promoting economic growth – but is by no means a sufficient condition. The adoption of managed undervaluation as a policy aimed at enhancing sustainable growth should be preceded by an in-depth analysis of its welfare implications. Policymakers have to be aware that the costs of such a policy may overcome the benefits in the medium to long term. To be successful, this policy must also be accompanied by other necessary and complementary conditions, such as strong institutions and sound macroeconomic conditions. Finally, a country must be prepared to exit this strategy before costs begin outweighing benefits.

References

Eichengreen, B. 2008. “The Real Exchange Rate and Economic Growth.” Working Paper No. 4. Commission on Growth and Development, World Bank, Washington, Dc.

Levy-Yeyati, E., and F. Sturzenegger. 2007. “Fear of Appreciation.” Policy Research Working Paper 4387

Heston, A., R. Summers, and B. Aten. 2009. Penn World Table, Version 6.3. Technical Report. Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Korinek A., and L. Servén. 2010. “Undervaluation through Foreign Reserve Accumulation: Static Losses, Dynamic Growth.” Policy Research Working Paper 5250. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Haddad M., and C. Pancaro. 2010. “Can Real Exchange Rate Undervaluation Boost Exports and Growth in Developing Countries? Yes, But Not for Long.” Economic Premise No. 20. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Rodrik, D. 2009. “The Real Exchange Rate and Economic Growth.” In Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2008,ed. D. W. Elmendorf, N. G. Mankiw, and L. H. Summers, 365–412. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

1 Authors' calculations. All coefficients are significant at the 1% level, but the coefficient for countries with $2500<real per capita GDP<$6000 which is not significant.

2 Authors' calculations. All coefficients are significant either at the 1% or at 5% level, but the coefficient for countries with $2500<real per capita GDP<$6000 which is not significant.

3 Authors' calculations. All coefficients are significant at the 1% level except for the contemporaneous coefficient for countries with $2,500<real per capita GDP<$6,000 which is not significant.

4 Authors' calculations. All lagged coefficients are not significant. All contemporaneous coefficients are significant at the 1% level except for the contemporaneous coefficient for countries with $2,500<real per capita GDP<$6,000 which is significant at the 10% level.

5 Authors’ estimates. Cross country relationship between average real GDP per capita growth and real exchange volatility for countries with GDP per capita income lower than $6,000 between 1980 and 2004. Coefficients are significant at the 1% level.

6 Authors’ estimates. Cross country relationship between average exports as % of GDP and real exchange volatility for countries with GDP per capita income lower than $6,000 between 1980 and 2004. Coefficients are significant at the 1% level but not significant if observations with real exchange rate variability above 0.4 are dropped.