Capital controls are no longer considered rogue policies.

- The IMF, in a striking switch, has accepted the use of capital controls when countries have few other options (Blanchard and Ostry 2012)

- Others have gone further, offering the opinion that capital controls could become a regular tool of policy (Jeanne, Subramanian and Williamson 2012).

This shift reflects the belief that countries that routinely block capital flows, such as China and India, were insulated from financial turmoil during the crisis (Ostry et al. 2010). It also acknowledges the role that controls on capital inflows could play in thwarting unwanted exchange rate appreciation.

While longstanding Chinese efforts to manage the value of the renminbi through the use of capital controls are viewed with concern, there is more sympathy for countries like Brazil that, during the crisis, imposed capital controls as appreciation pressures mounted. Even Swiss policymakers spoke of the possible use of controls on capital inflows as the franc strengthened against the euro and the dollar (Financial Times 2012).

There is a distinct and important difference, however, between long-standing capital controls, like those of China, and those employed episodically, as in Brazil.

Long term versus episodic capital controls

In my recent work (Klein 2012), based on the experience of 44 countries over the period 1995 to 2010, I distinguish between:

- 'Walls', long-standing capital controls; and

- 'Gates', episodic controls.

I find that ‘gates’ do not help with medium-run measures such as growth and appreciation, but ‘walls’ might. The cross-country regression analysis presented in my paper provides no evidence that episodic capital controls contribute to higher annual rates of GDP growth, lower annual rates of exchange-rate appreciation, or less buildup of positions associated with financial vulnerabilities. There is some evidence, however, that exchange-rate appreciation in China was lower than expected, and this could point to the role played by its long-standing capital controls.

Walls and gates in theory

A key distinction between walls and gates is that evasion is easier in countries that use controls episodically than in those that have long-standing controls. Countries with long-standing controls are more likely to have invested in the institutions needed to control capital flows. Controls are less permeable when they apply to wide categories of asset flows, as is the case for countries with long-standing controls, than when they are targeted to a subset of assets, which occurs with episodic controls. Capital controls also are more efficacious in countries with less sophisticated capital markets which have limited scope for financial innovation. Countries with long-standing capital controls have relatively repressed and underdeveloped financial markets, perhaps because they are much poorer than countries that use controls episodically, but also because prior exposure to international capital markets tends to be associated with financial development (Klein and Olivei 2008).

Theoretical arguments for capital controls implicitly distinguish between gates and walls. There is little theoretical support for long-standing, pervasive capital controls because these violate straightforward gains from intertemporal trade. There is a stronger case for episodic controls that could promote financial stability. Theory suggests that optimal controls on capital inflows would be procyclical, strengthening as capital flows increased. But the practical implications of this theory might be limited, beyond the issues of the efficacy of episodic controls. For example, the optimal tax in these models is typically quite small, and, in reality, taxes of this magnitude might be considered inconsequential by investors at a time of a rapid appreciation or a vibrant boom that substantially raises returns in affected markets1.

Theory also points out that capital controls could best contribute to financial stability if they are imposed in a particular 'pecking order', with controls placed on assets such as short-term debt before equities or direct investment. But, among the countries studied in my BPEA article, there is little evidence that controls on inflows were imposed in a manner consistent with pecking order considerations. Of the 23 instances of the imposition of inflow controls over the period 1995 to 2010, representing the experience of 18 countries that used controls episodically, there were only five cases consistent with pecking-order considerations.

The Brazilian experience

While theoretical arguments for capital controls centre on their possible role in promoting financial stability, recent inflow controls appear to be directly responding to currency appreciation rather than representing a forward looking effort to stem financial vulnerabilities. Most notably, in the fall of 2010, Guido Mantega, the Brazilian finance minister, claimed that monetary policies in advanced countries represented a 'currency war' against emerging markets. The Brazilian government had already imposed a 2% tax on investment in existing Brazilian equities on 20 October 2009 (the Imposto sobre Operações Financeiras, known by its initialism IOF). In the wake of the proclamation of the ‘currency war’ and continued real appreciation, the IOF was raised to 4% on 5 October 2010, and to 6% less than two weeks later.

QE2

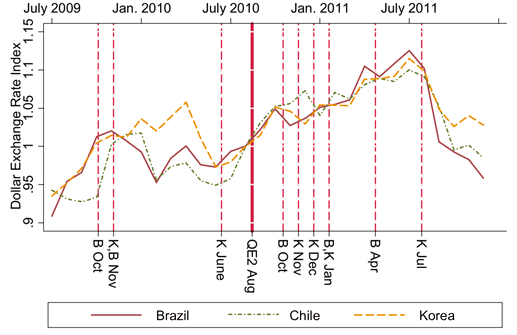

An examination of this experience casts doubt on the efficacy of episodic capital controls to affect currency values. The chart below shows the value of the Brazilian real, the South Korean won, and the Chilean peso from the summer of 2009 until the end of 2011. Each of these currencies appreciated against the US dollar during much of this time, with the rate of appreciation rising in the wake of the announcement of further quantitative easing, ‘QE2’, in August 2010. Both Brazil and South Korea imposed controls during this period, especially after the QE2 announcement, as shown by the vertical lines in Figure 1 (with ‘B’ and ‘K’ denoting which country imposed controls). Chile, in contrast, eschewed controls, perhaps as a result of its prior experience with its own controls in the 1990s – the encajé – which most observers believe did not influence the peso’s value.

Despite the differences in stances towards capital controls, the dollar exchange rates of the won, real and peso followed very similar paths over this period. Furthermore, efforts to stem the appreciation of the real and the won in the wake of the QE2 announcement do not appear to have been effective, with an ongoing appreciation of these currencies – and of the peso – until the summer of 2011. The subsequent parallel depreciation of these currencies in the second half of 2011 may be due to the relative slowing of GDP growth in these countries, but it is hard to associate the capital controls with currency movements. This is consistent with research on other episodes, such as the Chilean encajé, which failed to find evidence that capital controls affected exchange rates.

Figure 1. Capital inflow controls and exchange rates around QE2

Conclusions

A good argument that shows episodic capital controls to be effective remains to be made. The apparent success of longstanding capital controls in countries like China and India – at least along some dimensions – tells us little about the consequences of capital controls imposed or removed in countries like Brazil and South Korea, as circumstances change. Walls and gates are fundamentally distinct, and the policy debate must take these differences into account.

References

Bianchi, Javier, and Enrique Mendoza (2010), “Overborrowing, Financial Crises and ‘Macro-Prudential’ Taxes”, NBER Working Paper, 16091.

Blanchard, O and Jonathan D Ostry (2012), “The multilateral approach to capital controls”, VoxEU.org, 11 December.

Financial Times (2012), “Swiss feel the pain of franc’s safe status”, 30 May.

Jeanne, Olivier, Arvind Subramanian, and John Williamson (2012), Who Needs to Open the Capital Account, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Klein, Michael W (2012), “Capital Controls: Gates versus Walls,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, forthcoming, also published as an NBER Working Paper, 18526, November.

Klein, Michael W and Giovanni Olivei. 2008. “Capital Account Liberalization, Financial Deepness and Economic Growth”, Journal of International Money and Finance, 27(6), 861 – 875.

Korinek, Anton (2010), “Regulating Capital Controls to Emerging Markets: An Externality View”, mimeo, University of Maryland, December.

Ostry, Jonathan, Atish Ghosh, Karl Habermeier, Marcos Chamon, Mahvash S Qureshi, and Dennis B S Reinhardt (2010), “Capital Inflows: The Role of Controls”, IMF Staff Position Note, SPN/10/04.

1 For example, Korinek (2010) calculates an optimal tax of 0.44% on Rupiah debt and 1.54% on dollar debt while Bianchi and Mendoza (2011) calibrate a model using US data and find an optimal prudential tax on debt of 1%.