Expansionary fiscal policy is back in vogue. According to Bloomberg, the number of news stories with the keywords “fiscal stimulus” skyrocketed this summer to levels not seen since 2008. It is not just words. Fiscal policy has already become more stimulative in some countries. Canada led the way after the election of Prime Minister Trudeau, and Japan recently announced a large multi-year fiscal package. Quietly, fiscal policy has started to contribute positively to growth even in the US and the Eurozone, after years of austerity. Recent G20 statements all contain a version of the sentence, “We will use fiscal policy flexibly”.

What does ‘‘using fiscal policy flexibly’’ mean? It should be obvious, but it is not. The reason it is not obvious is that there is a strong intellectual anchoring effect in economic policy that has led to a very asymmetric view of fiscal policy.1 The pre-crisis consensus on the use and scope of fiscal policy was very strong, and remains strong today. The business cycle would be managed by monetary policy, while fiscal policy would focus solely on debt sustainability. In that world, fiscal policy was asymmetric. A smaller deficit and a smaller debt/GDP ratio were always better. That was a world of growth near potential, inflation at or above target, and positive nominal and real interest rates. That was the Great Moderation. That world created economic rules like the Eurozone’s Stability and Growth Pact, and many of the heuristics that economists use today.

The problem is that we remain anchored in the past, and we continue to apply today the same pre-crisis rules and heuristics about fiscal policy, ignoring the fact that we no longer live in that world. We live in a world of persistent insufficiency of demand, too-low inflation, and neutral real interest rates that are likely to be zero or even negative.2

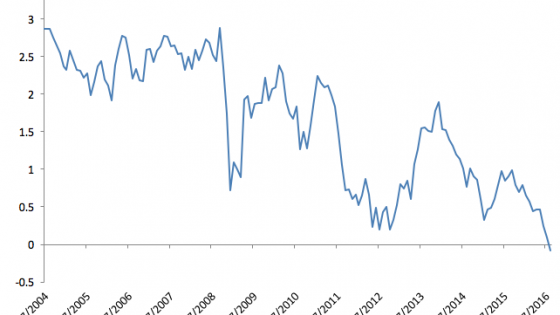

And this new world is expected to persist. Looking far into the future, financial markets expect a continuation of very low interest rates. For example, Figure 1 shows the US real 10-year swap interest rate, 10 years forward. It has declined markedly, from around 2.5% during 2004-2007 to about zero today. And the pattern is similar for the rest of the G7. Markets could certainty be wrong. But this pricing implies a very long period of zero real interest rates, a rather depressing outlook.

Figure 1 US 10y10y real interest rate

Source: Bloomberg

In this world of zero interest rates, fiscal policy has to contribute to supporting aggregate demand and protecting against deflationary risks. Monetary policy alone cannot do it. It is possible that the elasticity of demand with respect to interest rates may have declined. A heightened aversion to debt, and a decline in the confidence that monetary policy alone can restore growth and inflation, could be dampening the effectiveness of monetary policy. The old framework is no longer valid.

If we apply the old framework to today’s reality, if we fail to stimulate the economy, we risk that hysteresis transforms persistent weakness in demand into lower potential growth, as Blanchard et al. (2015) show. In this world of zero interest rates, contractionary fiscal policies may lead to higher, not lower, debt/GDP ratios.

A well-designed expansionary fiscal policy stance can contribute to better economic outcomes in three ways.

- First, it can boost potential growth with multi-year public investment packages that raise productivity.

The multi-year nature of public investment would contribute to credibly lifting growth and inflation expectations. Public investment does not have to be limited to bricks and mortar; it can be anything that a given country needs to eliminate bottlenecks, including investment in human capital and spending to support those displaced by the reforms. With long-term interest rates at zero, there are surely many long-term public investment opportunities that can deliver positive returns and boost potential growth. In addition, at a time of excessive risk aversion, risk taking via public investment can catalyse private investment and unleash a virtuous circle. It will crowd in private investment, rather than crowd it out. With very low interest rates, the multiplier of fiscal policy is likely to be very large. As DeLong and Summers (2012) argue, public investment that boosts potential growth is self-financing.

- Second, it can help monetary policy become more effective by increasing the supply of government bonds and raising the equilibrium real interest rate.

With very low neutral real interest rates, central banks have had to buy large amounts of government bonds to reduce long-term interest rates to zero, or even below, in order to provide enough stimulus. These central bank purchases are facing the constraint that financial institutions want to preserve some holdings of positive yielding bonds and are reluctant to sell them, creating a severe scarcity effect that creates a vicious circle of ever lower interest rates and flatter yield curves. The recent shift in strategy by the Bank of Japan, abandoning its target for asset purchases and refocusing its attention on targeting interest rates, is testimony to the difficulties central banks are facing to keep the needed monetary accommodation. A fiscal expansion would, in addition to boosting demand, increase the supply of government bonds and alleviate this scarcity (see also the discussion in Caballero et al. 2015). By reducing global savings, it would also increase the equilibrium real interest rate, amplifying the stimulus provided by monetary policy.

- Third, it can contribute to reducing income inequality.

The strategy of focusing only on monetary policy to support demand may have contributed, at the margin, to the recent increase in inequality, as the main transmission mechanism of monetary policy at the zero bound has been asset price appreciation, which benefits disproportionally asset holders. Employment income growth has been steady in this recovery, but it has been a combination of solid job creation and stagnant wage growth. There is a risk that economies fall into a low wage-growth trap, as has happened in Japan during the last two decades. A well-designed public investment programme could generate higher-paying jobs and boost productivity. Combined with an expansion of income policies, as the IMF recommends to Japan in its 2016 Article IV report, it would lead to increasing wage growth, reducing inequality and buying political goodwill for reforms (see, for example, the proposals in Enderlein, Letta et al. 2016).

A typical criticism of this call for active fiscal policy is that there is no fiscal policy space, especially in the Eurozone. This is a debatable statement, given the very strong demand for government bonds that is pushing long-term interest rates to record low levels. And, in any case, it is time to create the fiscal space by accelerating the creation of a European fiscal policy, including Eurobonds (see the discussions in Ubide 2015, 2016b).

This call for a more active fiscal policy is not a call for fiscal irresponsibility. It is a call to break the intellectual anchoring effect of the Great Moderation that creates an asymmetric bias against fiscal policy. This need for symmetry in fiscal policy to support monetary policy is not just old fashioned Keynesianism, as it appears in a variety of theoretical frameworks, such as the fiscal theory of the price level (Sims 2016). Once growth and inflation pick up in a sustainable manner, it will be the time for fiscal consolidation. But, for now, with interest rates expected to be very low for a very long period of time, fiscal policy will have to be the main economic policy to support growth in the foreseeable future.

References

Blanchard, O, E Cerrutti and L Summers (2015), “Inflation and Activity—Two Explorations and their Monetary Policy Implications”, IMF Working Paper 15/230.

Caballero, R, E Farhi and P-O Gourrinchas (2015), “Global Imbalances and Currency Wars at the ZLB”, NBER Working Paper 21670.

DeLong, B and L Summers (2012), “Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring: 233–274.

Enderlen, H, E Letta, et al. (2016), Repair and Prepare: growth and the Euro after Brexit, Berlin: Gutersloh and Paris: Bertersmann Stiftung, Jacques Delors Institut.

Sims, C (2016), “Fiscal Policy, Monetary policy and Central Bank Independence”, paper presented at the 2016 Kansas City Fed Symposium.

Tversky, A and K Daniel (1974), “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” Science, 185:1124–1131.

Ubide, A (2015), “Stability Bonds for the Euro Area”, PIIE Policy Brief 15–19.

Ubide, A (2016a), “The case for an expansionary fiscal policy in the developed world”, Business Economics, July.

Ubide, A (2016b), ‘‘A New Fiscal Policy for Europe.’’ PIIE Real Time Economic Issues Watch.

Endnotes

[1] This anchoring effect is, in the spirit of Tversky and Kahneman (1974), the tendency to rely excessively on the initial pieces of information to form subsequent judgements. I made this point in Ubide (2016a).

[2] The neutral real interest rate implicit in the September 2016 Fed’s dot plot, solving it with an inertial Taylor 1999 rule, would be currently negative, and not turn positive until 2019.