In recent decades, several countries have demonstrated that it is possible to move from low-income to high-income levels within a human lifetime. Most of these development success stories are located in East Asia. Understanding their successes is important for poor countries, but also for the socio-economic outcomes in the world’s largest country, China.

So far, China has also been developing at rates similar to those of its neighbours. It took only 40 years for China's income classification to move from 'very low' to 'upper-middle'.

But it is not clear whether China’s growth model is sustainable: growth rates are slowing, and structural problems are accumulating. Some economists have shifted their focus from understanding 'growing like China' (Song et al. 2011) to analysing 'slowing down like China' (Zilibotti 2017). The structures and institutions created to help the Chinese economy industrialise may not be well-suited to promote innovation and productivity growth. Wei et al. (2017) have shown that in recent years Chinese growth has been driven by factor accumulation. The evolution of total factor productivity (TFP) has made no (or even a negative) contribution to GDP growth.

The middle-income trap

A 2007 World Bank report warned that Asia’s developing economies may become stuck in the middle-income trap (Gill and Kharas 2007). The idea is that moving from middle-income to high-income status may be qualitatively different from the shift from low-income to middle-income status. Some countries that have transitioned to middle-income status successfully (and even rapidly) may stop converging to high income levels if they fail to transform their institutions, structures and policies.

The idea that different types of policies or institutions are growth-enhancing at different stages of development was first developed by Acemoglu et al. (2006), building on the Schumpeterian growth framework (Aghion and Howitt 1992, Aghion et al. 2014). Economies that are far from the productivity frontier can catch up with advanced economies using an investment-based model, adopting technologies developed elsewhere. This growth model requires large capital investments and often involves the centralised coordination of those investments by the state or by large business groups.

But as the economy gets close to the frontier, growth comes from inventing in new technologies, rather than importing them. The economy must shift to an innovation-based growth model that requires a high-skilled workforce, investment in advanced research and development, plus a dynamic competitive environment involving competition between decentralised firms, their entry, and their exit.

Large-scale institutional transformation is hard. In this case the transformation would be from an investment-based growth model’s institutions to those of an innovation-based model. An investment-based model creates powerful interest groups that want to preserve the status quo ante – in particular their preferential access to capital, and protection from competition in factor and product markets.

And so the investment-based model may overstay its welcome, which is bad news for the country's productivity growth and economic development. This is the typical scenario of an economy that gets caught in the middle-income trap.

Escaping the trap

The quintessential example of transition from investment-based to an innovation-based model is the Republic of Korea, a country that grew successfully using its investment-based model until the 1997-98 Asian crisis. Between 1963 and 1997, Korean GDP per capita grew at an average of 7% per annum – one of the most successful growth episodes in history. The pre-crisis model was structured around large conglomerates, known as chaebols. The government supported the chaebols through de facto preferential access to credit, explicit and implicit bailout guarantees, and by limiting competition from independent domestic and foreign direct investors (Chang 2003), among other ways.

This model delivered impressive results for more than 30 years, but the crisis undermined the legitimacy of the model and opened a window of opportunity for reform.

Pro-competitive reform proposals had already been discussed in the Republic of Korea, but the crisis created a feeling of humiliation because a fast-growing country was forced to seek support from the IMF. This created political support for change. The Republic of Korea undertook sweeping reforms, restructuring inefficient chaebols and removing entry barriers for non-chaebol firms and for foreign investors.

The anti-trust agency strengthened enforcement: corrective orders increased threefold, and the financial penalties for anti-competitive behaviour increased by a factor of 25 (Shin 2003). Foreign direct investment grew from 0.5% to 2% of GDP (Yun 2003). The removal of explicit and implicit support for chaebol members opened the Korean economy to competition. This helped renew economic growth after the crisis, growth that was based on innovation rather than factor accumulation.

In the early 1990s, the Republic of Korea filed eight times fewer patent applications to the USPTO than Germany. In 2012 it overtook Germany, and in 2015 the Republic of Korea filed 30% more patent applications to the USPTO than Germany, despite having roughly half the population and less than half of Germany's GDP.

How did the Korean transformation take place?

We have undertaken a granular analysis of firm-level data (Aghion et al. 2019) using the census of Korean manufacturing firms between 1992 and 2003, and therefore before and after the 1998 reforms. This meant we could analyse firm dynamics in industries that used to be dominated by chaebols, relative to those in other industries.

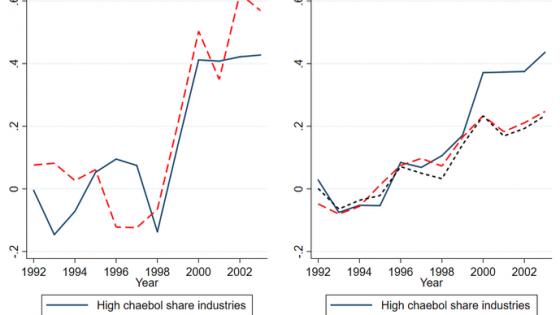

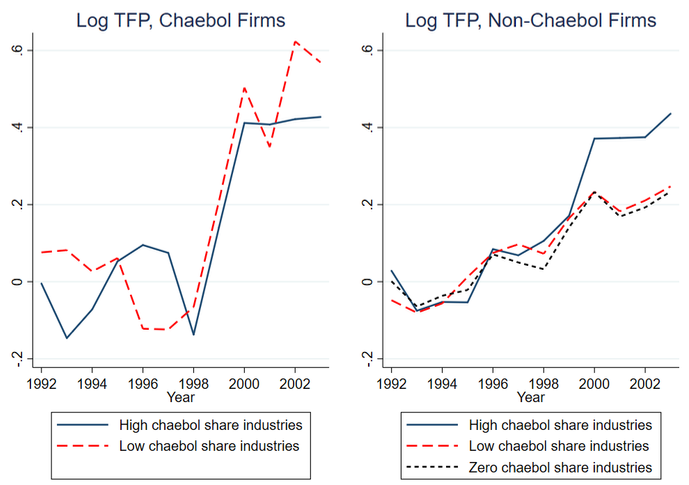

Our results are consistent with the predictions of the Schumpeterian growth paradigm. Before the crisis TFP was stagnating or even falling, especially among the chaebol firms. After the reforms rapid TFP growth resumed – both in chaebol firms and independent firms (Figure 1).

TFP growth was especially impressive in the industries previously dominated by chaebols, the sectors most affected by the reforms. In these industries, non-chaebol firms demonstrated particularly fast productivity growth. Entry of non-chaebol firms increased significantly in all industries after the reform.

Figure 1 Logarithm of total factor productivity (relative to average 1992-97) in chaebol and non-chaebol firms in industries with high, low and zero chaebol share

Source: Aghion et al. 2019.

Notes: The figures are logarithms of averages of each industry’s TFP for chaebol and non-chaebol firms, after winsorizing top and bottom 1% for the whole sample period in each industry categories. Industries are classified by average 1992-97 chaebol share: high (above 1992-97 median, 20%), low (below median), and zero. Industry-level log TFPs are normalised by 1992-97 average = 0.

Firm-level data on patenting activity also confirm that the reforms helped promote innovation. The growth came mostly from non-chaebol firms. Before the crisis chaebol firms had slightly faster growth of patents per year, relative to their non-chaebol counterparts. After the crisis annual number of patents by chaebol firms stopped growing, while patenting by non-chaebol firms accelerated.

The results confirm the success of the 1998 reforms in the Republic of Korea, and they also deliver important lessons for China. There are striking similarities between the Republic of Korea in the 1990s and China today, in which the role of Korean chaebols is played by large state-owned banks (SOBs) and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that control the commanding heights of the economy. In the Republic of Korea, it was a crisis that paved the road for pro-competitive reforms. Whether and when China will restructure its SOBs and SOEs remain open questions.

References

Acemoglu, D, P Aghion, and F Zilibotti (2006), "Distance to Frontier, Selection, and Economic Growth", Journal of the European Economic Association 4(1): 37–74.

Aghion, P, and P Howitt (1992), "A Model of Growth through Creative Destruction", Econometrica 60(2): 323-351.

Aghion, P, U Akcigit, and P Howitt (2014), "What Do We Learn From Schumpeterian Growth Theory?", in P Aghion and S Durlauf (eds), Handbook of Economic Growth, Volume 2: 515-563, Elsevier.

Aghion, P, S Guriev, and K Jo (2019), "Chaebols and Firm Dynamics in Korea", CEPR Discussion Paper 13825.

Chang, S-J (2003), Financial Crisis and Transformation of Korean Business Groups, Cambridge University Press.

Gill, I, and H Kharas (2007), An East Asian Renaissance: Ideas for Economic Growth, World Bank.

Shin, K (2003), "Competition Law and Policy", in S Haggard, W Lim, and E Kim (eds), Economic Crisis and Corporate Restructuring in Korea: Reforming the Chaebol, Cambridge University Press.

Song, Z, K Storesletten, and F Zilibotti (2011), "Growing Like China", American Economic Review 101(1): 196–233.

Wei, S-J, Z Xie, and X Zhang (2017), "From 'Made in China' to 'Innovated in China': Necessity, Prospect, and Challenges", Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1): 49-70.

Yun, M (2003), "Foreign Direct Investment and Corporate Restructuring After the Crisis", in S Haggard, W Lim, and E Kim (eds), Economic Crisis and Corporate Restructuring in Korea: Reforming the Chaebol, Cambridge University Press.

Zilibotti, F (2017), "Growing and Slowing Down Like China", Journal of the European Economic Association 15(5): 943–988.