China was one of the original contracting parties to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947, but its status was deactivated in 1950 after the formation of the People’s Republic. For the next three decades, China had practically no contact with the agreement. But the situation changed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, following Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms.

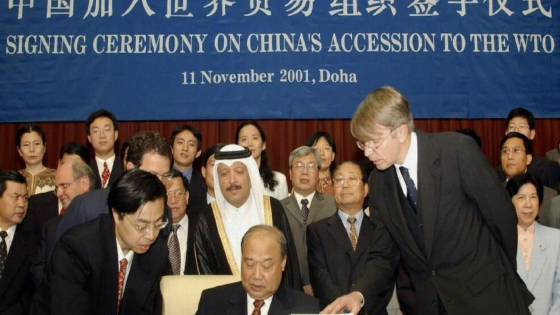

China formally sought the resumption of its status as a contracting party to the GATT in 1986, with accession negotiations starting the following year. Despite 20 rounds of negotiations, China and the incumbent GATT members failed to reach an agreement by 1995, when the WTO succeeded GATT. It then took another 18 rounds of negotiations for the two parties to agree on China’s ‘Protocol of Accession’ to the WTO.

The exceptionally long accession negotiation reflected the challenge of having a country with a socialist economic system and the largest population in the world join an organisation conceived and operated on essentially liberal economic principles.

Despite some apprehension, China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 was hailed as a magnificent achievement that would stay in history as the indelible etching on the wall commemorating the definitive victory of the liberal paradigm. But 20 years later, the mood has changed radically. Today, newspapers headlines concerning China – in the Western world at least – are consistently negative. Increasingly, there is a feeling that perhaps China and the WTO are mutually incompatible.

What has changed during the past 20 years? China or the WTO? How can a seemingly happy marriage turn so sour so quickly? The answer is multi-faceted. China did not change. The problem is largely one of false expectations. The answer can also be seen as being a case of ‘sub-optimal contracting’.

We begin with a caveat: in this column, inspired by our recent book (Mavroidis and Sapir 2021), we discuss China in the WTO, not China in the world economy or China in the realm of international relations. We do not deny that there is an osmosis between the general and the specific. Allison (2017) offered a perspective in this context, when claiming that we are probably traversing yet another Thucydides’ trap. Nevertheless, while we take on board all these analyses, in what follows we concentrate on China and the WTO.

The GATT liberal understanding

Economists and historians alike have described ‘GATT-think’, both its explicit and its implicit dimension. In Baldwin’s (1970) classic account, the GATT is a tariff bargain, the value of which is insured through legal disciplines like national treatment, and non-violation complaints. Tumlir (1984), and Zeiler (1999) focus on the pre-requisites for the agreed GATT-think to function: a liberal economy.

This should not come as surprise at all: Irwin et al. (2008) have shown that a conscious decision was taken to restrict the number of seats around the GATT negotiating table to a homogenous nucleus of liberal market economies. This choice was consistent with the idea that GATT, besides being a trade agreement, was part of the arsenal of the West during the Cold War. Trade policy, after all, broadly defined, is national security policy – since it allows trading nations to have access to goods that could be critical in advancing national security concerns (Schelling 1971).

No one gate-crashed the party, but the club is not what it used to be

The GATT entered the world of international relations as an interim organisation that was meant to be eventually incorporated into the International Trade Organisation (ITO). The ITO was supposed to become a multilateral organisation. The GATT followed suit even though the ITO never saw the light of day. In part hoping to persuade them to change course, and in part in order to place a dent on the coherence of the Soviet bloc, the GATT gradually opened its doors to Poland and Yugoslavia (in the 1960s), then Hungary and Romania (in the 1970s). The incumbents did not find it necessary to translate the liberal understanding implicit the GATT into explicit legal disciplines, since all four countries were very small shares in terms of international trade.

The GATT was not amended when Japan joined GATT in the 1950s either, although the state played an important role in the Japanese economy, and many GATT incumbents were reluctant to accept Japan in their midst for this reason. Japan was, of course, a large economy, and its export-led growth model was viewed as a threat. In fact, some of the reactions to China’s attempt to access the GATT and then the WTO were very reminiscent of the reactions to Japan’s own efforts to enter the GATT-world.

Yet, there were also striking differences between the West’s reaction to Japan and China. These had to do with economics but also, and primarily, with geopolitics. Given the military occupation of Japan by the US at the time it joined the GATT, there was never any doubt that it would eventually espouse the Western economic model. Its membership of the OECD, with its various ‘codes of conduct’ (in line with the principles of economic liberalism), a decade after joining the GATT, was the clearest sign that Japan had joined the Western ‘club’.

This time is different

The GATT/WTO liberal understanding was still implicit when China knocked on its door. WTO incumbents assumed that with Deng’s reforms China had entered a one-way street, with market economy being the end destination. Buoyed by Fukuyama’s (1992) pronouncement of ‘the end of history’, they seemed to espouse the view that the definitive victory of liberalism had arrived, and the fall of the Berlin wall was only the beginning. As we note in our book, some US statesmen went so far as to state publicly that China would become not only a liberal market, but also a liberal democracy. Of course, there were sceptics too, especially in the US. But even they bought into a simplistic narrative: the US keeps its tariffs at the same level after China’s accession; China greatly reduces and caps its tariffs (from 25 to 9% for industrial products, and from 31 to 14% for farm products); and as a result, the US was bound to gain more than China, obtaining bilateral trade surpluses. Even those who did not buy into the ‘China changes’ story could see the huge potential economic benefits of accessing the world’s fastest growing market with the biggest population (soon to become the world’s biggest market). For many, China was the biggest prize of the 21st century.

The economic dream has become reality, but so have the frictions with China. Even if China had, like Japan, become a Western-style economy by becoming an OECD member, frictions have occurred, as they did with Japan. It is not possible to incorporate into the trading system a very large and very fast-growing economy without frictions. But what is different with China is that has retained substantial state involvement in the working of its economy, which is in direct contradiction with the WTO’s implicit liberal understanding.

China describes its economic system as ‘socialist market economy’. It is a mix of private initiative and state planning, where, unlike in Western economies, the state’s (or the Communist Party’s) role is paramount. Dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and omnipresent industrial policies, the Chinese economy leaves some room for the private sector. But according to official Chinese statistics (stats.gov.cn), the public sector made up 63% of total employment in 2019. While some opening of the economy has occurred over the years, and it is now possible to have ‘wholly-owned foreign enterprises’ (known as ‘Wofers’), privatisation has been slow (or at least slower than expected by China’s trade partners). No doubt, lots of assets have been corporatised, but corporatisation does not mean privatisation, as China’s trade partners have come to realise after the country’s accession to the WTO. We return to this issue in the next part of this presentation of our book.

References

Allison, G (2017), Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?, New York City, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Baldwin, R E (1970), “Non-Tariff Distortions of International Trade”, Brookings Institution: Washington, DC.

Fukuyama, F (1992), The End of History and the Last Man, New York City, NY: Free Press.

Irwin, D A, P C Mavroidis and A O Sykes (2008), The Genesis of the GATT, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Mavroidis, P C and A Sapir (2021), China and the WTO: Why Multilateralism Matters, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tumlir, J (1984), “International Economic Order and Democratic Constitutionalism”, ORDO: Jahrbuch für die Ordnung von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 34:71–83.

Zeiler, T W (1999), Free Trade, Free World, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.