At one point, most economists were interested in Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) patterns as a route to understanding how western firms could operate in the Chinese market more effectively. Times have changed. When a line-up of top European economists meet at an EU-sponsored event at the Shanghai Expo next week they will be equally interested in understanding the motivations of Chinese firms that have been investing in Europe over the last decade, and their impact on the EU economy. The prospect of Chinese FDI in a range of infrastructure projects playing a major role in Greece's fiscal recovery efforts highlights the relevance of this research.

China as an FDI generator

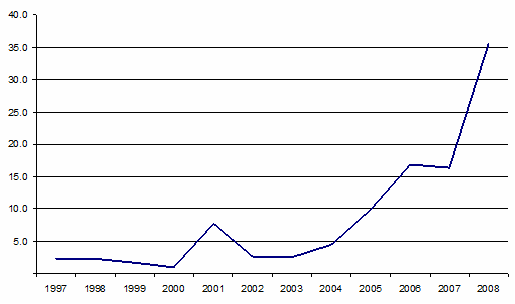

While China is now firmly established as one of the world's most important destinations for inward FDI, outward FDI by Chinese companies has also taken off spectacularly. Outflows doubled from 2007 to 2008 and expanded fourteen-fold between 2003 and 2008 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chinese outward FDI (€ billion)

Source: DG TRADE/ Eurostat

Despite the challenging economic environment, Chinese overseas investment continued to grow in 2009. According to data published by the Ministry of Commerce, outbound FDI by Chinese enterprises amounted to $43.3 billion in 2009, a year-on-year increase of 6.5%. This growth occurred against the backdrop of a decline in global FDI by up to 40% compared to 2008. Chinese overseas investment has thus proven remarkably resilient in the challenging conditions created by the financial crisis.

Much of the attention has been captured by large transactions, such as the take-over of Volvo by the Chinese carmaker Geely or Chinalco's bid for Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto. Yet a lot of activity takes place below the scale of these mega deals. A new study by the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (2010), in co-operation with the European Commission's DG TRADE and CEPII research institute1 provides a broad overview of Chinese outward FDI activity based on a detailed survey of 3,000 Chinese firms. This is the first time that firm-level information about Chinese FDI in Europe has been available at this level of detail. Thanks to the involvement of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, nearly half (46%) of the contacted firms replied to the extensive questionnaire.

The results indicate that Chinese firms' overseas activities are still at an early stage of development.

- Chinese firms are motivated mainly by access to improved distribution networks and advanced technology.

Accordingly, most projects involve setting up distribution centres and sales offices. Meanwhile, access to natural resources is an important objective of investments in developing economies.

- One quarter of the Chinese companies covered by the survey have made some type of overseas investment, although most of them are relatively small scale investments.

- 61% of responding firms indicated that their overseas investments remained below $1 million, while more than 80% of investments are below $5 million.

- Only a few companies have been capable of making large scale overseas investments in excess of $100 million.

- In terms of investment projects, overseas representative offices and sales offices are the most frequent types of overseas expansion routes adopted by Chinese enterprises.

- Some large companies, especially state-owned enterprises, have made cross-border mergers & acquisitions (M&A). In firms' future investment plans, M&A figure more prominently than in the past and activity can therefore be expected to pick up.

What this evidence suggests is that the sunk costs of engaging in FDI activities in Europe for small- and medium-sized Chinese companies are relatively low. Unlike the argument put forward by the "new-new trade theory", inward Chinese FDI in Europe does not seem to be confined to the "happy few" multinational or large companies with strong expansion potential (see Mayer and Ottaviano 2008 and Melitz and Ottaviano 2008).

Where and in what?

The sectoral and geographical breakdown of Chinese FDI in Europe offers additional insights.

- Most Chinese outbound investors are active in manufacturing sectors, although the industry profile is becoming increasingly diversified.

- Within the manufacturing industry, the textile and machinery and equipment sectors figure most prominently, reflecting China's strong export performance in these industries.

- Whereas most outbound investment in Europe has been aimed at enhancing market access through distribution and sales offices, manufacturing investment has been more significant for investment in developing economies.

- Apart from the manufacturing industries, companies active in construction and wholesales and retail operations are among the most active foreign investors.

Overall, the investment profile of the companies covered by the survey reflects China's presence in its export markets.

The selection of the Chinese FDI destinations is mainly driven by their market potential, in addition to their proximity to the Chinese market. Perceived strengths of the EU include the integrated market, the single currency and the good regulatory environment. Meanwhile, China's "Going Global" policy seems to be an important push factor in firms' outbound FDI activity. The study indicates that investment barriers do not play a major role among the factors influencing Chinese investment in the EU.

The main destinations for the overseas investments of Chinese enterprises are Asia, followed by Europe and North America, while only a few respondents have overseas investments in other regions. Asia, especially the Southeast Asian region which has a similar economic structure and cultural tradition, as well as long-standing commercial relations with China, has become the preferred destination for Chinese enterprises. We believe this situation will not change significantly for some time.

It is noteworthy that Vietnam, following its economic reforms, is becoming an important destination for Chinese investment. In terms of future investment plans, African destinations are becoming more important. They are seen as nearly equally important as a future investment location as the EU and North America.

When Chinese companies invest in the EU, the size of the local market seems to matter greatly.

- They mainly locate in Germany, France, Italy and the UK. Respondents' future investment plans show the same geographic profile.

- Smaller EU member states continue to be perceived as less attractive destinations, although Chinese enterprises consider the fact that the EU is an integrated market, has a single currency and a good regulatory environment as the main advantages of investing in the region.

- The most promising sectors for investing in the EU are considered to be manufacturing and wholesale and retail trade.

- The US remains a very important destination for Chinese FDI.

Chinese enterprises view overseas investments as a long term development strategy and respondent firms indicate a strong resolve to view overseas investments in a medium and long term perspective. While the scale of the respondents’ investments is generally small, over half of the respondent enterprises expressed an intention to increase overseas investments in the coming two to five years.

Impact of the crisis

As expected, the survey indicates that the overseas investments of most enterprises have been affected by the financial crisis. The financial crisis has caused economic recessions in many countries as well as a reduction in China’s domestic demand growth, which has made overseas investments more difficult for many Chinese enterprises. Moreover, access to financing for overseas investment has become difficult due to the crisis, and trade protectionism is perceived to be on the rise in some destination markets (see Evenett 2010). By contrast, some respondents identified positive effects associated with the crisis, such as weakened overseas competitors and the availability of acquisition targets at more attractive prices.

Results from statistical analysis of the data

An augmented gravity analysis (see appendix) including a number of structural parameters describing the institutional environment prevailing in different markets (such as the World Bank Doing Business indicators and OECD employment protection indicators) confirms the pattern emerging from the descriptive survey data. The regressions confirm the more anecdotal finding that Chinese companies tend to invest in countries with a large market size, a high level of economic development, and a favourable institutional environment.

Hence, the pattern emerging from the survey is that the behaviour of Chinese firms can be explained by much the same parameters as western firms' international activities. Perhaps the biggest surprise is that there are so few surprises in the data.

Yes, Chinese investors do mainly seek to build distribution channels for their exports and access to advanced technology. When they set up manufacturing activities they do so mainly in developing countries. African destinations are becoming increasingly important as a market for exports and for access to raw materials. The data thus reflect the overall level of development of the Chinese economy and its manufacturing enterprises.

From an EU perspective, encouraging findings include the fact that investment barriers are not perceived as a significant impediment to setting up operations in Europe. It is also heartening that Chinese investors seem to value a well-functioning institutional environment, including the integrated market.

What the survey of Chinese companies suggests is that Europe does have some strong selling points to promote in Shanghai. As Lao Tzu's famous saying goes, "a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step". For those Chinese companies that have invested in Europe that journey has begun quite promisingly, despite the more subdued economic climate. And despite complaints from some European businesses in China that the operating environment has become more difficult for them recently, the benefits of FDI are clearly recognized. Enhanced cooperation between China and the EU should thus aim at ensuring a level playing field for both Chinese and European companies.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the European Commission.

References

China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (2010), “Survey on Current Conditions and Intention of Outbound Investment by Chinese Enterprises”, April.

Evenett, Simon (2010), “Uneven compliance: The sixth report of the Global Trade Alert”, VoxEU.org, 23 June.

Mayer, Thierry and Gianmarco Ottaviano (2008), "The Happy Few: The Internationalisation of European Firms", CEPR Policy Insight 15

Melitz, Marc and Gianmarco Ottaviano (2008), "Market Size, Trade, and Productivity", Review of Economic Studies, (75):295-316

Appendix. Determinants of Chinese overseas investments

|

Dependant Variable: Number of Investments in Destination Country j

|

|

|

(1)

|

(2)

|

(3)

|

(4)

|

(5)

|

|

Ln Market Potential

|

0.357***

|

0.110***

|

0.229**

|

0.454***

|

-0.288

|

|

|

(0.0177)

|

(0.0304)

|

(0.112)

|

(0.134)

|

(0.331)

|

|

ln Distance

|

-0.0310

|

-0.304***

|

-0.506**

|

-1.540***

|

-7.281***

|

|

|

(0.0609)

|

(0.0670)

|

(0.244)

|

(0.362)

|

(1.797)

|

|

Ln GDP per capita

|

|

0.415***

|

0.263**

|

0.558***

|

-1.209**

|

|

|

|

(0.0397)

|

(0.108)

|

(0.173)

|

(0.513)

|

|

Ln (Ease of Doing Business)

|

|

|

0.131

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.105)

|

|

|

|

Ln (Starting A Business)

|

|

|

|

-0.0997

|

-2.214***

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.111)

|

(0.408)

|

|

Ln (Protection of investors)

|

|

|

|

-0.333**

|

1.757***

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.148)

|

(0.472)

|

|

Ln (Paying Taxes)

|

|

|

|

1.027***

|

-5.389***

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.226)

|

(1.499)

|

|

Ln (Trading Across Borders)

|

|

|

|

0.375**

|

0.741*

|

|

|

|

|

|

(0.147)

|

(0.402)

|

|

Ln (Employment Protection)

|

|

|

|

|

3.025*

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1.670)

|

|

Pseudo R2

|

0.279

|

0.359

|

0.433

|

0.547

|

0.676

|

All results are from ordinary poison regressions. Standard errors are in parenthesis. *,**,*** indicate respectively that coefficients are significant at 10%, 5% and 1%.

Source: CCPIT/ DG TRADE/ CEPII

1 Centre d'études prospectives et d'information internationale, Paris