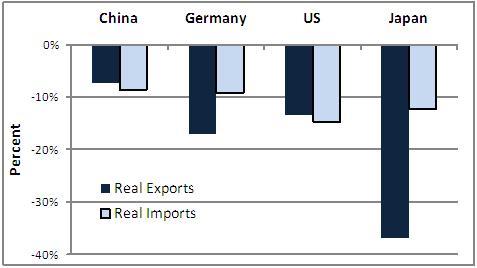

Between September 2008 and mid-2009, global trade suffered a sudden, severe, and synchronized collapse.1 Figure 1 illustrates that both real exports and imports declined substantially in the world’s four largest trading countries.

The experience of these countries was not unusual. According to the IMF, global (PPP-weighted) real exports declined by 14% between 2008 Q3 and 2009 Q1. While there has been a recovery in trade recently, 2009 is still likely to be the first year in which global trade has declined since 1982, and only the third such year in the past half-century.2

Figure 1. Change in real exports and imports: 2008Q3 to 2009Q1

Source: IMF GDS database. Data are seasonally adjusted.

Vertical specialization and intermediate goods trade

In a Vox column earlier this year, Yi (2009) suggested that vertical specialization provides a real transmission mechanism that may help explain the widespread decline in trade. The vertical specialization transmission mechanism is subtle, with several ways in which it could help generate a large and widespread collapse in trade:

- First, there could be re-nationalisation of international production chains (triggered perhaps by an increase in protectionism).

- Second, growing vertical specialization implies that more cross-border transactions occur between separate stages of the production process. If the elasticity of substitution across stages is very low, then shocks to production in one country could be transmitted forcefully to other stages undertaken elsewhere.

- Third, if demand shocks are concentrated on goods that are vertically specialized, then trade is highly sensitive to changes in demand (as in the Barbie example of O’Rourke 2009).

While all these channels seem plausible and many analysts have asserted that they have played an important role in the trade collapse, there has been, to date, little evidence supporting the notion.

New evidence on vertical linkages

In this chapter, we provide examples of some of the results emerging from our research on quantifying the consequences of intermediate goods import linkages for the transmission of shocks and collapse in trade. Our approach is based on measuring bilateral imported intermediate goods linkages using trade data combined with national input-output tables.

Imported intermediate-goods linkages arise any time a manufacturer uses imported intermediate inputs in its production process. When the manufacturer subsequently exports some of the resulting output, we say the production process is vertically specialized.3 This creates a tight connection between imported intermediate linkages and vertical specialization.

The importance of imported intermediate goods linkages

Imported intermediate goods linkages have several distinct implications for the response of trade to changes in final demand. These effects operate independently of, and in addition to, standard trade transmission channels that work through the endogenous response of final demand to shocks.

- First, imported intermediate goods linkages imply that a country's exports and imports tend to move in the same direction in response to changes in either domestic or foreign demand.

For example, a decline in US demand for cars will typically imply decreased demand for cars imported from Canada. Since Canadian cars are produced using imported inputs from the US, a decline in the production of Canadian cars will mean fewer US exports of car parts to Canada; both US imports and exports fall. This does not happen if the imported intermediates channel is absent.4

- Second, imported intermediate goods linkages influence each country's exposure to foreign shocks.5

This effect is subtle but nonetheless important.

The standard way to measure the extent of the international trade spillover of a shock in one country to another country is the amount of trade between the two countries, normalized by GDP or by total trade. Thus, if US import demand falls, a particular country, say Korea, may be hit hard because a large share of Korea’s exports goes to the US. However, Korea's export share to the US actually underestimates the strength of this linkage. Because Korea exports large amounts of intermediate goods to China, which then processes these goods into final goods and re-exports them to the US, the true bilateral linkage between Korea and the US is larger than the simple Korean export share to the US. To measure the true linkage, one needs to know the intermediate goods linkages between countries, as well as the final destinations of exports.

To this end, Johnson and Noguera (2009) have developed a global input-output system that facilitates the measurement of these “true” linkages.

Johnson-Noguera measures

A typical input-output table provides information linking industry output, demand, and trade vis-à-vis the rest of the world. Thus, it indicates, for example, the value of imported vehicle parts that are embodied in US motor vehicles that are either sold domestically or exported.

The contribution of Johnson and Noguera is that their input-output system links countries and sectors bilaterally. Thus, it indicates, for example, the value of Japanese motor vehicle parts that are embodied in US motor vehicles that are either sold domestically or exported to Canada.6

This is precisely the type of information that one needs in order to accurately measure how shocks propagate across countries and sectors, as it facilitates a calculation of the true impact of a reduction in demand in the US on Korea’s exports, imports, and GDP. Bems, Johnson and Yi (2009) draw from, and update, the system in Johnson and Noguera (2009) in order to examine the importance of vertical linkages in the propagation of the current global downturn.7

However, the global input-output system is not a panacea. It is an accounting framework, rather than a fully specified economic model. Final demand in this system is taken as exogenous. Thus there is no direct connection between final demand in one country and final demand in another country; endogeneity operates only through intermediate input channels.

This limitation, for example,rules out the situation where US demand for cars can affect Canada's purchases or production of steel and rubber is through intermediate linkages. In contrast, our accounting framework does capture all of the effects arising from an initial final demand shock, holding all other final demands constant. This is somewhat restrictive, but at least it captures important inter-country and inter-sectoral linkages via intermediates trade.

Three applications of the global input-output system

A few examples from Bems, Johnson and Yi (hereafter, BJY) help to illustrate that basic importance of vertical linkages.

In the first exercise, we subject final demand in each sector of the US (or the European Union) to a -1% shock. Table 1 reports the resulting decline in exports, GDP, and imports in nine different regions of the world; for multi-nation regions like the EU, we define exports ignoring intra-regional trade.

Table 1. Impact of a -1% aggregate demand shock.

Source: Authors’ calculations

As the figures show, US GDP falls 0.92% following the shock, which is not surprising given the small share of trade in GDP. US Imports in the US fall 0.95% – again not surprising, as a drop in final demand usually results in a large drop in imports. US exports, by contrast, fall by only 0.06%, reflecting the fact that the US is not, in the aggregate, tightly integrated into cross-border production networks.

The impact on other regions is more varied. China’s exports fall by 0.28%, very similar to the decline in Japan’s exports, which are 0.25%. These export responses are similar despite the fact that China exports approximately 60% more goods to the US than Japan in our data.8 The response is similar because a good deal of Japanese value-added is exported to the US through China and other countries.9 Importantly, the overall effect on China’s GDP is three times that of the effect on Japan’s; this reflects the fact that China’s GDP is considerably more dependent on exports.

Looking at Mexico and Canada – combined into NAFTA in the table – we see the US shock leading to substantial drops in both GDP and exports. GDP in Mexico and Canada falls by 0.22% and exports by 0.76%, reflecting the very large share of these nation’s exports that go to the US. Note that NAFTA imports fall by only 0.14%, but this is still larger than any other region because of relatively strong intermediate goods linkages within North America. Elsewhere, the US shock has more modest effects on GDP and exports abroad.

The simulation results for a hypothesised drop in EU by 1% are presented in the last three columns of Table 1. The results are broadly similar, but with Eastern Europe taking the place of NAFTA.

Sector-specific shocks

We believe that these effects, induced by a symmetric demand shock hitting all sectors equally, greatly understate the true role of trade in transmitting the global recession. In the current global downturn, there is ample evidence that some sectors have been hit harder than others.

The manufacturing sector, in particular, has suffered more than overall GDP in most countries. This asymmetry is important because manufacturing is more intensively engaged in trade and international production networks than the rest of the economy.

To assess the effects of an asymmetric sector-level shock, we consider a second exercise in which we hit only industrial sectors (i.e., manufacturing, construction, and utilities) with a shock calibrated to generate a 1% decline in aggregate final demand, thereby matching the overall decline in the first exercise. Table 2 presents the results.

Table 2. Impact of a decline industry equivalent to a -1% aggregate demand shock.

Source: Authors’ calculations

Turning first to the simulated results of a shock of this type that affects only the US (see first three columns of Table 2), we note immediately that, in comparison with Table 1, the effects on exports are considerably larger, usually about three to four times larger. For example, NAFTA exports fall by 2.34%, in contrast to the 0.76% fall in the symmetric shock case. This magnified effect stems, by and large, from the fact that industrial goods tend to be more widely traded than non-industrial goods and services. Additionally, exports by China and Japan fall by about 0.90% each.

With the export declines about three to four times larger, it is no surprise that the GDP declines in the different regions are also about three to four times larger than in the symmetric shock case. For example, GDP falls by 0.27% in China and by 0.58% in the NAFTA countries. Finally, the import effects are also considerably larger. This primarily reflects the fact that a larger decline in exports implies, through the imported intermediate linkages, a larger decline in imports.

The results for the EU shock, shown in the last three columns of Table 2 are broadly similar. These results are evidence that the international transmission mechanism can be quite strong when shocks are concentrated on internationally engaged sectors.

Simulation of industry-specific shocks in a world without vertical linkages

In the third exercise, we attempt to assess the importance of the imported intermediate linkages by conducting the following counterfactual. Suppose there are no imported intermediate linkages. Rather, all international trade is trade in final goods.10 We feed an industry-specific demand shock through this counterfactual model as in the previous scenario. Table 3 presents the results.11

Table 3. Decline in industry sectors equivalent to -1% aggregate demand shock with no intermediate input linkages.

Source: Authors’ calculations

Looking at the effects of a US shock in Panel A, we highlight first that US exports now experience zero decline. To understand this result, note that because the shock begins with US domestic demand, only US imports fall when all trade is in final goods. As discussed above, US exports can only be affected by US demand shocks through imported intermediate goods linkages in our framework, which have been eliminated in this counterfactual scenario. In the other countries and regions, export declines are typically one-third to one-half lower than in the second exercise. As a corollary to the zero decline in US exports, imports are unchanged in all regions other than the US. This again is due to the fact that other countries would only suffer a decline in imports if the production of their exports required imported intermediates. Hence, we can interpret the declines in imports in the previous exercises as the effect of vertical specialization. The results for the EU are again broadly similar.

Final notes

We believe that our analysis points to the importance of cross-country intermediate input linkages. It also points to the importance of specific sectoral shocks. We suspect that our framework understates the importance of these linkages, because, as we noted, we employ an accounting framework that does not capture feedback effects from final demand shocks to other countries’ final demand. If these feedbacks were operative, there would be additional transmission of demand changes via imported intermediate input linkages. Last, it should be noted that our results suggest that much of the trade collapse is a result of falling final demand. Thus, as demand recovers, we expect trade to recover as well.

Footnotes

1 The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Federal Reserve System, or the International Monetary Fund.

2 Source: World Bank, WDI database, World exports in 2000 $U.S.

3 Note that it is possible to have imported intermediate goods linkages across countries without having vertical specialization. But it is not possible to have vertical specialization without having imported intermediate goods.

4 The standard "demand spillovers" trade transmission mechanism implies that exports fall in response to changes in foreign, not domestic, demand. This standard mechanism generates positive co-movement between exports and imports only if domestic and foreign demand are positively correlated. In contrast, imported intermediate goods linkages cause exports and imports to move together in response to changes in domestic demand alone.

5 Though we focus on the implications of imported intermediate linkages for measurement of bilateral linkages in the main text, these links are also important for measuring aggregate openness and hence overall exposure to foreign shocks. Typically, the aggregate intermediate goods consistent measure of openness does not equal either exports to GDP or exports to total output.

6 Also, see Wang, Powers, and Wei (2009) and Fukao and Yuan (2009), among others, for related work using Asian input-output tables. Daudin, Rifflart and Schweisguth (2009) also work with a global input-output system.

7 Specifically, we employ the GTAP7 database, which has data through 2004 and covers 94 countries plus 19 composite regions.

8 In 2004, the base year in our data, China exported about $211 billion of goods to the United States, while Japan exported $133 billion.

9 See Ruyhei Wakasugi’s chapter in this Ebook for an elaboration of this point.

10 We implement this counterfactual by re-defining all imported intermediates as imported final goods, and by “zeroing” out the imported intermediates matrix. In doing this, we preserve gross output, exports and imports, but value-added is no longer consistent with the original matrices. No rearrangement of the input-output tables that eliminated imported intermediate linkages can preserve all the variables.

11 We do not examine GDP, because our counterfactual leads to pre-shock GDPs that are no longer consistent with the original GDP (see footnote 8).

References

Bems, Rudolfs, Robert C. Johnson, and Kei-Mu Yi. (2009). “The Role of Vertical Linkages in the Propagation of the Global Downturn of 2008.” In process.In preparation for conference on “Economic Linkages, Spillovers and the Financial Crisis”, January 2010, organized by the IMF Research Department, the Banque de France and the Paris School of Economics.

Daudin, Guillaume, Christine Rifflart and Danielle Schweisguth. (2009). "Who Produces for Whom in the World Economy?" OFCE Document de travail, No. (2009)-18.

Fukao, Kyoji and Tangjun Yuan. (2009). "Why Is Japan So Heavily Affected by the Global Economic Crisis? An Analysis Based on the Asian International Input-Output Tables." VoxEU.

Johnson, Robert C. and Guillermo Noguera. (2009). “Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value-Added.” Manuscript. Dartmouth College.

O’Rourke, Kevin. (2009). “Collapsing Trade in a Barbie World” The Irish Economy.

Tanaka, Kiyoyasu. (2009). “Trade Collapse and Vertical Foreign Direct Investment.” VoxEU.

Wang, Zhi, William Powers, and Shang-Jin Wei. (2009). “Value Chains in East Asian Production Networks: An International Input-Output Model Based Analysis.” Manuscript, US International Trade Commission.

Yi, Kei-Mu. (2009). “The Collapse of Global Trade: The Role of Vertical Specialisation” in The Collapse of Global Trade, Murky Protectionism, and the Crisis: Recommendations for the G20, Richard Baldwin and Simon Evenett, eds., March 2009, 45-48.