There is an increasing public policy debate asking whether market power has become ‘too big’ and, if so, what the aggregate implications are. A number of recent studies have documented that concentration ratios are on the rise, in particular in the US but also potentially at a global level. These studies also show that the degree of imperfect competition is rising and business dynamism has fallen, where imperfect competition is proxied by mark-ups, i.e. the ratio of price to marginal cost, and business dynamism by the birth and death rate of new establishments and jobs (e.g. De Loecker and Eeckhout 2017, 2018, Dıez et al. 2018, Dottling et al. 2017, Autor et al. 2017a). However, our understanding of these trends at the euro area and global level is still limited. One line of discussion is focused on whether we are witnessing similar trends in the euro area as in the US.

Our recent work aims to contribute to this discussion by using a comprehensive approach relying on micro- and macroeconomic data along three dimensions: market concentration, mark-ups and labour dynamism (Cavalleri et al. 2019). Limitations in data quality and data availability imply that we focus our analysis on the four largest euro area countries, namely Germany, France, Italy and Spain.1 For the macro database we use the sectoral data of KLEMS, and for the micro data we use a combination of Orbis and iBACH (starting 2006 onwards). One clear conclusion is that the euro area in recent decades has experienced distinct developments compared to the US. Market power metrics have been relatively stable over recent years. This is a feature of both the macro and micro data. This might be considered a surprising outcome since we typically consider the US and the euro area to be not only at a relatively similar level of development, but also to have been characterised by relatively similar secular trends in recent decades.2 However, our results suggest that shifts in market power are not the main reason behind those particular developments.

Main results

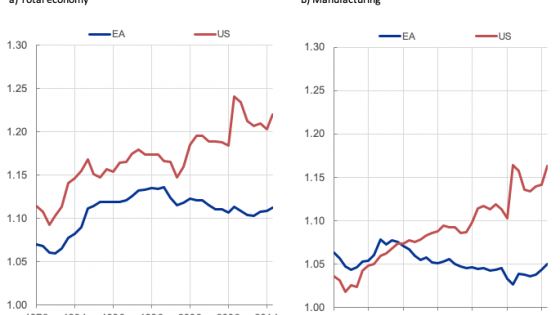

More concretely, our macro data analysis shows that the aggregate euro area mark-up from the four biggest countries was around 15% between 1980 and the late 1990s, and has since declined marginally. From a sectoral perspective, this was largely the results of developments in manufacturing, possibly driven by the impact of deeper trade and monetary integration in the euro area (see Figures 1a and 1b). The firm-level data, which covers a shorter sample period of 2006-2015, largely confirms this picture (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 Mark-up evolution

Source: Cavalleri et al. (2019).

Note: Last observation refers to 2015.

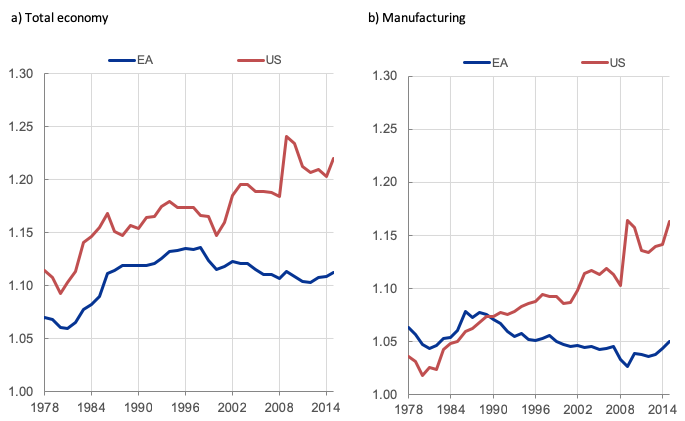

Figure 2 Evolution of weighted mean mark-up versus the mark-up of the top four firms across sectors in the four biggest euro area countries

Source: Cavalleri et al. (2019).

Note: Calculations based on firm-level data. Last observation refers to 2015.

This does not imply that there are no industries or firms within the euro area that have high and/or rising mark-ups, but only that such firms are not those with particularly high market shares on average. The findings that the rise in mark-ups at the aggregate level has been driven by an increase in the mark-up of large firms (see De Loecker and Eeckhout 2017 for the US) appears not to hold in the euro area, as Figure 2 shows.

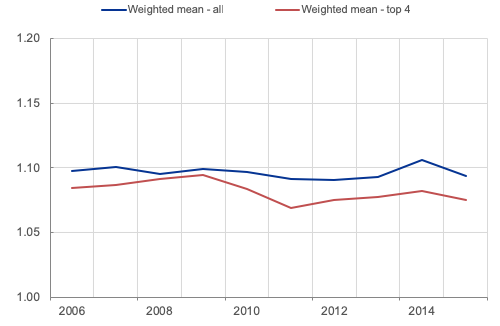

In terms of concentration ratios, we find that they have remained broadly stable in the euro area in recent years, both at the aggregate and at the national level. Moreover, we find that concentration is higher at the country level than at the single market aggregate level, i.e. when taking the euro area as a whole. To illustrate, Figure 3 shows the concentration ratio for the top four firms in manufacturing.

Figure 3 Evolution of the CR4 over 2006-2105 by country in manufacturing

Source: Cavalleri et al. (2019). The charts measure the combined market share of the top 4 firms (CR4) in each 2-digit industry of the manufacturing sector, summarised for the total manufacturing sector as indicated.

Note: Calculations based on firm-level data. Last observation refers to 2015.

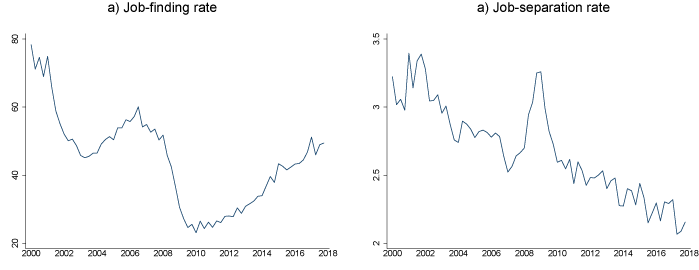

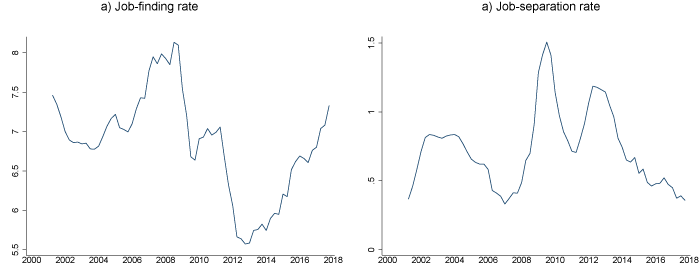

Our final dimension to analyse market power is job market dynamism. De Loecker and Eeckhout (2017) argue that higher market power can explain the decline in labour market flows in the US. To compare the US with the euro area, we use the approach of Shimer (2012) and the refinement of Elsby et al. (2013) and compute job-finding and job-separation rates. This method has the advantage of providing comparable estimates across the two regions.3

Figures 4 and 5 plot the estimates for the US and the euro area from 2000 to 2018. For the US, we note both a clear cyclical pattern in the job-finding rate but also a trend decline. Concretely, at the end of the sample, the job-finding rate is still below its pre-crisis peak despite unemployment being below its pre-crisis trough. The behaviour of the job-separation rate is starker, being on a clear secular downward trend throughout the period examined. For the euro area, the picture looks different. While the level of either rate, as is well-known, is an order of magnitude lower than the US, no particular change in the trend of labour market dynamics seems to have taken place. Instead, fluctuations of dynamism are fully explained by the cycle.4 All in all, while labour markets in the US remain substantially more dynamic than the ones in the euro area, this dynamism has fallen substantially over the past two decades, signalling a clear structural change. By contrast, no such change can be detected for the euro area.

Figure 4 Job-finding and job-separation rate in the US (%)

Note: Job-finding and separation rates estimated as in Shimer (2012), using the redesign adjustment suggested by Elsby et al. (2013).

Source: BLS.

Figure 5 Job-finding and job-separation rate in the euro area (%)

Note: Job-finding and separation rates estimated as in Shimer (2012), aggregated across durations using the optimal weighting method of Elsby et al. (2013).

Source: Eurostat.

Implications and the way forward

Exploiting both macro and micro data for the four largest euro area countries, we have found, in contrast to the assessment for the US, there has been no trend decline in job dynamism and that mark-ups and concentration ratios appear relatively stable. A key question that arises from these findings is whether we should consider euro area developments as positive or negative. The conventional view is that – in a static sense, at least – a rise in market power is generally welfare-reducing since it results in firms charging too high prices and producing too little output relative to the competitive benchmark. At the same time, firms that have a dominant market position may underinvest relative to a more competitive environment and may erect barriers to new, potentially more innovative, firms (OECD 2005). On this basis, from a welfare perspective, it could be argued that recent developments might be more favourable for the euro area.

The link between the market power of a firm and its economic performance, however, is far from straightforward. Market power can also be viewed in a positive light. The prospect of enjoying some market power (and profits) can be the main incentive for firms to invest and innovate. If firms were not able to appropriate the results of their investments, they may not invest or innovate at all. This could deprive consumers of higher quality goods and/or new product varieties. From this perspective, it could be argued that the euro area has missed out on the superstar firms, which enjoy some market power but also have the incentive to invest and to innovate.

To understand better whether the recent euro area developments have been positive in some dimensions, we investigate the relation between concentration ratios, investment, total factor productivity (TFP) and mark-up developments at the sectoral level. We find that firms in sectors which exhibit high concentration but are categorised as ‘high tech’ users generally are associated with higher TFP growth rates. By contrast, mark-ups tend to display a bi-modal distribution when looked at through the lens of high concentration and high-tech usage: there is a tail of firms with above-average mark-ups and below average mark-ups. This suggests that welfare and policy analysis of market power and concentration is complex and requires further research. Indeed, both theoretically and empirically, competition intensity and welfare can have very disparate relationship across different sectors (Syverson 2019).

A better understanding is also needed of the rise of global firms and their complex ownership structures. The boundaries of the firm are becoming less defined than before, and complex ownership structures across firms are increasingly common. This new reality generates substantial data challenges but also raises questions. How do euro area firms respond when competing against global giants? Does the presence of these firms in European markets raise (home) productivity or does it choke off the rise of home rivals? The answers to these questions would require better data on various dimensions of firms’ performance, such as their ownership structure, innovation activities, and dependence on global value supply chains. These are important policy-relevant questions for future research, which require a concerted effort to gather comparable data and to back-date richer firm-based data, including the universe of firms in euro area countries.

References

Autor, D, D Dorn, L Katz, C Patterson and J Van Reenen (2017a), "Concentrating on the fall of the labor share", American Economic Review 107(5): 180–185.

Autor, D, D Dorn, L Katz, C Patterson and J Van Reenen (2017b), "The fall of the labor share and the rise of superstar firms’, NBER working paper 23396.

Baqaee, D R and E Farhi (2018), "Productivity and misallocation in general equilibrium", NBER working paper 24007.

Cavalleri, M-C, A Eliet, P McAdam, F Petroulakis, A Soares, and I Vansteenkiste (2019), "Concentration, market power and dynamism in the euro area", ECB discussion paper 2253.

De Loecker, J and J Eeckhout (2017), "The rise of market power and the macroeconomic implications", NBER working paper 23687.

De Loecker, J and J Eeckhout (2018), "Global market power", NBER working paper 24768.

Dıez, F, D Leigh, and S Tambunlertchai (2018), "Global market power and its macroeconomic implications", Working paper 18/137, International Monetary Fund.

Dottling, R, G Gutierrez and T Philippon (2017), "Is there an investment gap in advanced economies? If so, why?", presented at the 2017 ECB Forum on Central Banking (Sintra).

Elsby, M, B Hobijn and A Sahin (2013), "Unemployment Dynamics in the OECD", Review of Economics and Statistics 95(2): 530-548.

OECD (2005), "Policy roundtables: Barriers to entry 2005", OECD Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, Competition Committee.

Shimer, R (2012), "Reassessing the jns and outs of unemployment", Review of Economic Dynamics 15(2): 127–148.

Syverson, C (2019), "Macroeconomics and market power: Facts, potential explanations and open questions", Brookings Economic Studies.

Endnotes

[1] This should nevertheless allow us to obtain a rather comprehensive picture, since these four countries combined represent 76% of euro area GDP.

[2] Among these secular trends are, for example, investment rates and productivity growth rates slowing, real interest rates declining, and inflation rates being muted.

[3] In Cavalleri et al. (2019), we also examine the more common metric of business dynamism (i.e., the birth and death rate of new firms), but these data are less well-suited to such an analysis, due to differences in coverage, definitions and conventions across countries.

[4] This is confirmed when regressing the finding rate on unemployment.