The coronavirus shock began with disruption to China-related supply chains and the fall in demand for exports to Asia. Subsequently, the disruption to foreign travel and the enforced domestic social distancing, and ultimately lockdown at regional or city levels, together constituted a mix of extreme supply and demand shocks. The multiple impacts of the virus and of medical containment measures on the circular flow of income in an economy are illustrated in Figure 1 in Baldwin (2020). Central banks have responded by lowering interest rates, giving additional liquidity support, and with QE, with the aim of supporting asset values and credit flows. Fiscal authorities have taken unprecedented steps to support companies, employees and the self-employed in the face of these shocks.

The largest falls in the US in the last 100 years in quarterly income and in aggregate consumption will be seen in the second quarter of 2020. Normally, one thinks of consumption as being less volatile than income. There are two reasons for this: there are lags in the adjustment to shocks, and also a potentially stabilising influence on consumption of expectations of future income.

This time, however, we are likely to see a radical reversal of this pattern. This will occur for multiple reasons. These include the fact that part of the shock comes from consumption itself, that the jump in the unemployment rate greatly increases income insecurity and hence raises precautionary saving, and that lower asset prices and tighter credit availability also lower consumption.

Below, we first set out the empirical structure for a consumption function that can actually capture the above effects. Then we set out a plausible scenario for the US after the Covid-19 shock, by making plausible assumptions about the size of the factors mentioned in the previous paragraph. Then the negative effect on US consumption in the second quarter of 2020 can be estimated.

Empirical evidence from a consumption model

The basis is to examine empirical estimates of the drivers of consumption, building on research published in Aron et al. (2012) and Duca and Muellbauer (2013). These papers generalise a textbook permanent income model by setting out a ‘credit-augmented consumption function’. They make four crucial extensions to the stylised textbook model.

- First, the credit channel is explicitly incorporated by the inclusion of credit conditions indices for unsecured credit and for mortgage credit.1

- Second, household balance sheets are split into liquid assets and debt, illiquid financial assets and housing wealth. This allows the more realistic measurement of different propensities to consume from the components of wealth rather than combining all into a single net worth sum.

- Third, a far higher discount rate is applied to future income streams than in the textbook model. This rests on an aggregate approximation to the behaviour of heterogeneous agents facing liquidity constraints and it is justified by the buffer-stock theory of saving (see Muellbauer 2020 for further explanation).2

- Fourth, there are short-term roles for income insecurity, proxied by the change in the unemployment rate, and cash flow effects on indebted households are captured by changes in interest rates.

A vast and complex general equilibrium problem underlies the economic situation faced by the US. A large econometric model is ideally required to capture this, but no satisfactory models exist. A single equation model or a household sector sub-system (as estimated for France, for example, in Chauvin and Muellbauer 2018) can provide useful, quick insights into some of the key issues. This type of ‘credit-augmented’ consumption equation has been estimated for a range of other countries as well as for the US and shown itself to be robust over time.

To develop scenarios, assumptions need to be made about the multiplier process through which falls in consumer spending feed into employment and income generation. Further assumptions address how the financial system responds to these shocks and how contagion may arise within the financial system, affecting credit availability (see Lustig and Mariscal 2020 for warnings on how this could evolve.

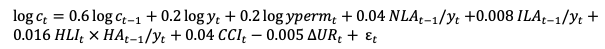

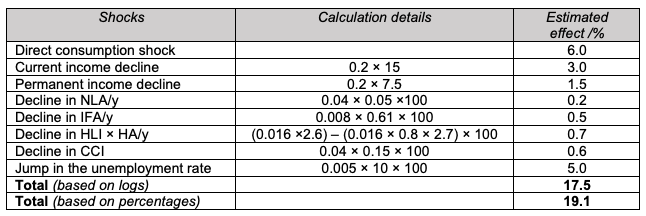

The credit-augmented consumption function as estimated for the US (Duca and Muellbauer 2013) is presented as follows (all in constant prices),3 with the variables defined in Table 1.

Table 1 Variable definitions

Note that the 25% per annum discount to discount future income flows implies a much shorter horizon than in textbook models, but it is the same as that assumed in the Federal Reserve’s FRB-US model.

Speed of adjustment

To interpret the model, note that the log of lagged consumption appears on the right-hand side of the equation with a coefficient of 0.6. Hence, to obtain the long-run solution, this requires division of the coefficients on log y and all other terms (apart from the change in the unemployment rate) by 1-0.6=0.4. This is known as the speed of adjustment.4 The speed of adjustment here suggests plausibly that almost 90% of adjustment to a shock occurs within one year. By contrast, in inadequately specified consumption equations in the structural econometric policy models at some central banks, speeds of adjustment are mostly below 0.2 (Muellbauer 2020). This implies an implausibly slow adjustment to a shock. Quite apart from slow adjustment, many of these models also omit an important variable – the effect of unemployment.

Income

The equation is sensible in that it imposes long-run homogeneity. That is, if income and all components of wealth double, then consumption doubles as well. This is achieved by imposing that the sum of the two income coefficients is 1 in the long run, and that the wealth terms are expressed as ratios to income. The equation is also consistent with micro-evidence from heterogenous agent models, on which there is a large recent literature. In particular, as noted in Muellbauer (2020), the model is consistent with the micro evidence from Crawley and Kuchler (2018) that the marginal propensity to spend is highest for asset poor households, intermediate for those with illiquid assets (such as housing wealth) but no liquid assets, and lowest for the doubly asset rich.

Turning to the aggregate estimates, for the total of consumers, the equation parameters suggest that the marginal propensity to consume out of aggregate current income is around 0.2 within the quarter, and around 0.45 after four quarters. This could have implications, for example, for how quickly a fiscal ‘helicopter money drop’ might be spent. However, what is valid in normal times needs to be adjusted for current circumstances. First, buffer-stock saving theory suggests that higher income uncertainty lowers the time horizon so that, at this time of record household uncertainty, the weight on current income should rise relative to that on permanent income. This implies a higher likely marginal propensity for US consumers to spend out of income. Second, given that the fiscal transfer to households benefits much more households who are poor both in income and in wealth, an important distributional effect is implied by the evidence of Crawley and Kuchler (2018). The higher marginal propensities to spend of these households will push up the average spending response, thus making a ‘helicopter drop’ even more effective.

The housing collateral effect, credit conditions and unemployment

The largest differences in consumption behaviour among countries is related to the housing collateral effect, the effect of shifts in credit conditions and the unemployment effect. This is suggested by my empirical work with co-authors on several other countries. For instance, the housing collateral effect is absent in many European countries where home equity withdrawal is almost unknown (see Chauvin and Muellbauer 2018 on France, Geiger et al. 2016 on Germany). The effect of shifts in credit conditions will be greater where indebtedness is higher. Further, the effect of a change in the unemployment rate is far greater in the US than in European countries with stronger social safety nets.

The wealth components

There is another major source of heterogeneity across countries: the differences in financial balance sheets relative to income. Germany has a far higher ratio of liquid financial wealth minus debt than the US and a far lower ratio of stock market wealth to income. It will therefore experience a less negative household reaction to these shocks than the US. The coefficients on the liquid and illiquid wealth components can be interpreted as the marginal propensities to consume out of different types of wealth. For example, a $100 increase in illiquid financial assets will raise annual consumption by $2, after full adjustment to this increase has occurred. However, this is not the only way that the stock market affects consumption. It also plays an important signalling role for how households forecast their future income.

A bird’s-eye view

The model is useful in thinking about the multiple channels through which the shocks triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic transmit: first, the direct effect of the shock of consumption; then its indirect effects on income and unemployment, on households’ expectations of income, on the components of wealth through asset price changes, and via the changing credit conditions. Any attempt to forecast using the equation has to make heroic assumptions about several key factors. Amongst these, fundamental is the ability of the health system to cope, and the efficiency of government policies on social distancing and eventually lockdown, as this drives the timing of supply shocks. The trade-off between drastic intervention on social distancing to stem the rate of infection and short- and longer-term economic damage is well explained in Gourinchas (2020) and in Baldwin and Weder (2020). Also important are assumptions concerning government support packages to keep businesses afloat and to support household income, the extent of stock market and housing market declines, and, as noted above, the ability of financial system to cope with the coming wave of corporate bankruptcies and loan defaults across the spectrum.

On health systems and the speed of government response, the analysis of Pueyo (2020a, 2020b), provides evidence on differences between countries in health systems and the speed and scale of government responses. The US does not emerge well from this comparison. The rapid efforts across much of Europe to enforce social distancing while infection rates were still low and to provide speedy financial support to companies and households contrasts with an inadequate early response in the US, both on the health and the economic fronts. These differences suggest that the US is likely to suffer a greater degree of long-run economic damage than much of Northern Europe.

A US scenario

I set out below what I believe to be a plausible economic scenario for US consumption, following the Covid-19 shock. I also consider a somewhat more positive scenario than this. The analysis reflects the mechanisms set out in Figure 1 of Baldwin (2020). It also draws on experience from the admittedly rather different global financial crisis of 2008, on the interaction between the financial system and the real economy.

A plausible economic scenario

To begin, examine the consumption shock itself. Consider the most vulnerable (from a Covid-19 perspective) of the broad components of total private consumption expenditure at the end of 2019: restaurants and hotels (at 7% of total consumption expenditure), transport services (at 3.3%), recreation services (at 4.1%) and gasoline and other energy (at 2.3%). There is also likely to be a more generalised shock because a lockdown makes shopping more difficult and delivery services will not be able to compensate entirely, at least in the short run. Thus, the contribution of food consumed at home, currently at 7%, will undoubtedly increase. The other major beneficiary is healthcare, which measured 17% of spending at the end of 2019.

For the most sensitive components of consumption, the scenario for the second quarter of 2020 for the consumption shock looks like this:

- A decline from 7% to 2% in restaurants and hotels. Some of the former will convert to home delivery, and some hotels will be converted to hospitals. This raises questions about how the national income accountants will measure the new activities and I assume they will not reclassify in the short-run and simply measure sales in this sector.

- A decline in transport services from 3.3% to 1% as airport travel contracts.

- A decline in recreation services – gyms, theatres, cinemas, concert venues etc. – from 4.1% to 1.5% as live activities collapse, and there is some switch to online substitutes.

- A rise in food at home from 7% to 10% in constant price terms. Price rises are likely to make the rise in share measured in current prices greater than when measured in constant prices.

- A rise in healthcare spending from 17% to 20%, probably constrained by capacity, and a constraint that could increase as medical staff themselves are infected. A similar point on current vs. constant prices applies here too.

The net effect so far is a decline in total consumer spending of 3%.

- However, there will surely be a decline in other goods and services simply because of the constraints on shopping and the disruptions in supply chains. I will assume this accounts for another 3%, which is probably quite a modest assumption.

This overall 6% decline in total consumer spending is separate from any effects that operate via the other channels represented in the model.

- I am also assuming that the postponement of purchases of durables is mainly part of the process of adjustment to the income, wealth, credit and unemployment rate drivers.

We turn to assumptions about income:

- I will assume that log labour income, log y, falls by 0.15 in the quarter, which corresponds to a fall of 16 percentage points. This takes into account the within-quarter multiplier effects of the consumption shock and the supply shock across the economy. However, it makes a fairly optimistic assumption about the cash support provided by the federal government to household incomes and to companies.

- I will assume that the log of permanent labour income, log yperm, falls by 0.075, (7.8 percentage points) around half the fall in current labour income. There are indications that the health crisis will last a year or more and that some disruption to the economy will continue for longer as re-infection from foreign countries with still virulent epidemics remains a risk.

Turning to the household balance sheet effects, these balance sheets are measured at the end of the quarter, i.e. at the end of March. This is a slightly artificial assumption made to make asset values independent of current quarter consumption shocks when estimating the equation. Clearly, asset prices in, for example, April, will have some impact on consumption measured as the total for April, May and June. The assumptions below reflect this.5 Further, in computing asset to income ratios, I will work with a slightly more sophisticated income measure, which is the average of current and permanent labour income, corresponding to the equal weights they receive in the equation.6

- The ratio to ‘adjusted’ income of net liquid assets, NLA/y, was around 0.15 at the end of 2019 – and it is assumed to decline to 0.1, as cash reserves are drawn down and credit lines, especially via credit cards, are used.

- The ratio to income of illiquid assets, ILA/y, was around 6.8 at the end of 2019. I assume that when the impact of bankruptcies, loan defaults and payment delinquencies ripple into the financial system, the late March stock market valuations will not be sustained.

- In this scenario, the stock market falls by 40 percentage points.7

To assess the likely implications, note that stock market wealth plus the value of privately held non-corporate shares amount to around 58% of total illiquid financial assets. Bonds, defined benefit pensions and other illiquid financial instruments account for the rest. In the global financial crisis, these pensions and instruments more than held their value.

- With bond yields already at lows at the end of 2019, it seems likely that they will simply hold their value, suggesting a fall in the value of total illiquid financial assets of 21%. With current and permanent labour income down by respectively 16 and 7.8 %, the, the ratio of illiquid financial wealth to adjusted income, falls by around 9%, a fall of 0.61

Finally, there are assumptions about housing wealth, credit conditions and unemployment. The ratio of income to gross housing wealth, HA/y, was around 2.6 at the end of 2019. House prices are sticky, so any short-run decline in house price indices as measured by the Federal Housing Administration will be outweighed by the decline in adjusted income, leaving the ratio at 2.7.

- Crucially, however, the housing liquidity index, HLI, is assumed to contract from 1 by 0.8 because of the disruption to credit markets and the rise in risk aversion. Unfortunately, later in the year, house prices are likely to fall, probably feeding back negatively on HLI, with longer-term consequences. Reasons for the fall include the decline in income, the contraction of credit conditions and the prospect of more housing coming onto the market given deaths among the elderly population.

- I assume the credit conditions index for unsecured consumer credit falls from 1 to 0.85, as payment delinquencies soar.

- I will assume that the unemployment rate in the second quarter of 2020 jumps by 10%. While unprecedented, this is probably a rather conservative assumption. Back of the envelope calculations from the St. Louis Federal Reserve envisage a worst-case increase of 32.1%, but this does not consider recent fiscal measures.

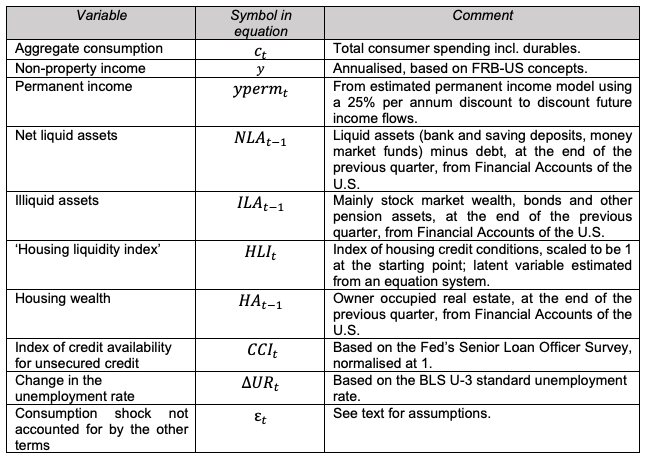

With these assumptions, we can now add up the negative effect on consumption in the quarter (see Table 2).

Table 2 Estimated percentage change in consumption

Note: The model is formulated for log income and log consumption. For small changes, the change in log x 100 is a close approximation to the percentage change. For larger changes, this approximation breaks down, e.g. a 0.15 change in log income translates to 16 percentage points.

The grand total is close to a 19 percentage point fall in quarterly consumption, which exceeds the 16 percentage point fall in labour income. I have probably underestimated the role of the current income decline since, as mentioned above, the rise in uncertainty makes households concentrate much more on the near term. This could increase the grand total to around 20%. One qualification of this analysis is that data for March 2020 will already have been affected by some of these factors, though on a more modest scale. This means that some of the process of adjustment will already have begun late in the first quarter of 2020, which could reduce the relative magnitude of the second quarter decline compared to the first quarter.8

A more positive economic scenario

It is also possible to consider a more positive economic scenario, with the following assumptions: a 5% pure consumption shock, a 14% decline in labour income and a 7% decline in permanent income, a 25% fall in the stock market, a smaller decline in the housing liquidity index from 1 to 0.9, and a smaller decline in unsecured credit conditions from 1 to 0.9. Similar calculations then suggest an improvement of around 2.4% in the second quarter for the consumption outlook compared to the main scenario. This would imply a fall nearer 15% than 19%, but still in excess of the 14% fall in labour income.

As data for April arrive, it will be possible to refine potential scenarios. In the very short run, the assumptions about the pure consumption shock, the jump in the unemployment rate and the fall in labour income are those that matter the most. Every 1 percentage point additional rise in the unemployment rate directly reduces consumer spending by half of 1% – and by more once the second-round effects on income are considered.

By the third quarter of 2020, the direct consumption shock should have partially reversed as long as virus control measures have succeeded, and supply chains improved. Most of the unemployment shock effect will probably have dissipated. However, lower house prices are likely to be a further drag on consumption. According to the model, 0.6 of the second quarter’s fall in consumption would feed through in the third quarter. This would lower consumption by a further 11 percentage points, other things being equal. A further feedthrough would occur in the fourth quarter.

More than a modest recovery in the stock market from the 40% decline assumed in the main scenario is also unlikely. Among several reasons are widespread bankruptcies, and the wiping out of cash reserves for many companies, which will lead to major cuts in dividend pay-outs when profits recover as companies seek to rebuild reserves. Further, the explosion of government debt issuance could stress sovereign bond markets and cause yields to rise, particularly in the absence of some monetary finance of fiscal policy. The ‘Fed model’ of stock market valuation would then imply lower values than the end of 2019 levels. Finally, the rise in risk aversion after such a catastrophe is likely to constrain stock market valuations for some time. Overall, the reversal of supply constraints and some improvement in the unemployment rate are likely to lead to far smaller changes in total consumer spending in the third relative to the second quarter, as positive and negative factors tend to offset each other.

Conclusion

The outlook for US consumption and for the economy appears far grimmer than at any time in the 2008 global financial crisis. At least in peacetime, the most monumental tasks that any US government will ever have faced will include dealing with the health consequences of the virus, restoring supply chains, preventing capacity from being permanently lost, supporting consumer income and spending, and supporting the financial sector to keep credit flowing. Health capacity – as measured by the ratios of population to intensive care beds, testing kits and ventilators – is significantly worse in the US than, for example, in Germany, and access to these is more unequal. Further, the vulnerability of US households to declines in income, asset prices and credit availability is far greater than in Germany (the UK situation is likely to be somewhere in between). While state and city governments in the US have taken the lead, delays in clear communication on social distancing by the federal government will have increased the strain on the health system and the ultimate death toll. This is likely to delay subsequent economic recovery. For evaluating the consumer spending consequences beyond the second quarter, the above framework is useful and can flexibly adapt to evolving scenarios as new data arrive.

Author’s note: I am grateful for helpful discussions with Janine Aron, Eric Beinhocker, Doyne Farmer, David Vines and members of INET@Oxford’s complexity group, but take full responsibility for errors.

References

Aron, J, J Duca, J Muellbauer, K Murata, and A Murphy (2012), “Credit, housing collateral and consumption in the UK, US, and Japan”, Review of Income and Wealth 58(3): 397-423.

Baldwin, R (2020), “Keeping the lights on: Economic medicine for a medical shock”, VoxEU.org, 13 March.

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (2020), Economics in the Time of COVID-19, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Carroll, C D (1992), “The Buffer-Stock Theory of Saving: Some Macroeconomic Evidence”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 23(2): 61-156.

Chauvin, V and J Muellbauer (2018), ”Consumption, household portfolios and the housing market in France”, Economie et Statistique/Economics and Statistics 500-501-502: 157-178, plus online complement.

Crawley, E and A Kuchler (2018), “Consumption Heterogeneity: Micro Drivers and Macro Implications”, Danmarks Nationalbank Working Paper 129, November.

Deaton, A (1991), “Saving and Liquidity Constraints”, Econometrica 59(5): 1221-48.

Duca, J V and J Muellbauer (2013), “Tobin LIVES: Integrating Evolving Credit Market Architecture into Flow of Funds Based Macro-Models.”, ECB Working Paper No. 1581, European Central Bank. Also in B Winkler, A van Riet, and P Bull (eds), A Flow-of-Funds Perspective on the Financial Crisis Volume II—Macroeconomic Imbalances and Risks to Financial Stability, Palgrave Macmillan 2014.

Faria-e-Castro, M (2020), “Back-of-the-Envelope Estimates of Next Quarter’s Unemployment Rate”, On the Economy Blog, St. Louis Federal Reserve, March 24, 2020.

Geiger, F, J Muellbauer and M Rupprecht. (2016), “The housing market, household portfolios and the German consumer”, ECB Working Paper Series 1904.

Kaplan, G and G L Violante (2018), “Microeconomic Heterogeneity and Macroeconomic Shocks”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 32(3): 167-94.

Lustig, N and J Mariscal (2020), “How COVID-19 could be like the Global Financial Crisis (or worse)”, in R Baldwin and B Weder di Mauro (eds), Economics in the Time of COVID-19, VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press, 185-190.

Muellbauer, J (2020), “Macro-financial linkages and the micro-evidence-based foundations of policy models”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy (forthcoming).

Pueyo, T (2020a), “Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now’, blog, revised 19 March 19.

Pueyo, T (2020b), “Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance”, blog, revised March *, 2020.

Toda, A A (2020), “Covid-19 Dynamics and Asset Prices”, in Covid Economics 1, CEPR Press.

Endnotes

1 The latter is interacted with housing collateral – as varying access to home equity credit determines the spending power of housing wealth.

2 Seminal papers on buffer-stock saving include Deaton (1991) and Carroll (1992), and various later papers by Carroll. A non-technical overview of recent literature on heterogeneous households facing liquidity and credit constraints and uncertain incomes is given by Kaplan and Violante (2018).

3 The numerical estimates have been rounded and come from an update of the equation published in Duca and Muellbauer (2013). All estimates are significant at least at the 99% level. Omitted are the real interest rate and changes in nominal rates on floating rate debt, since no major short-run changes of consequence are likely to occur, at least not of a beneficial nature. Higher risk spreads on lending rates could have a further negative impact.

4 This is more evident when rewriting the model as: Δlog c = 0.4 (0.5 log y + 0.5 log yperm + etc. – log c-1).

5 For example, applying a monthly version of such a model to quarterly data would suggest that average asset values for April and May would be relevant for consumption averaged over April, May and June.

6 This is justified by the fact that the equation above is a log-approximation to an underlying equation that reflects additive budget constraints. The adjusted income measure we will use for scaling assets helps improve the approximation

7 For comparison, the fall in the values of directly and indirectly held stock market wealth of households from 2007Q3 to 2009Q1 was close to 50%. The current crisis is more serious, though it does not originate in in the financial system. Indeed, corporate debt to GDP levels are even higher than in 2007. There is likely to be contagion within the financial system, despite the stricter macroprudential controls of recent years. Indeed, Toda (2020) uses an asset pricing model to suggest a 50% fall in the stock market.

8 It is assumed that real consumer spending in the first quarter is little changed from the last quarter of 2019. The US stock market peaked in February. The effect of the March rise in the unemployment rate and of early supply shocks will have been largely offset by hoarding of non-perishable consumption items.