Provisioning standards prevailing before and during the Global Crisis were based on the concept of incurred losses. They were criticised for excessively delaying banks’ recognition of credit losses, and thus being a source of procyclicality (Financial Stability Forum 2009). In response, the International Accounting Standards Board and the US Financial Accounting Standards Board introduced new rules based on the concept of expected loss. In the EU and a good part of the rest of the world, IFRS 9 entered into force in 2018, while in the US, the current expected credit loss (CECL) approach is scheduled for 2021. With some differences, both standards call for the recognition of credit losses that, on the basis of available information (including macroeconomic information), can be expected to occur over horizons varying from one year to a credit instrument’s lifetime. The goals behind this more forward-looking approach to provisioning included inducing more cautious lending behaviour in good times and prompting earlier corrective action in bad times.

Many observers and the proponents of the new standards got intellectually captured by the idea that provisions based on ‘expected’ rather than ‘incurred’ losses ought to be less procyclical. However, the complicated internal modelling required to estimate future credit losses under IFRS 9 and CECL would be truly countercyclical only if the bank modellers were able to predict turning points in the cycle, or the arrival of disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic two or three years in advance. In such circumstances, they would be called to nurture their provisions (loss absorbing buffers) at the right time: against the profits made in the two or three years before the cycle turns or the disaster arrives. This would make the banks enter the contraction with additional buffers.

Expected loss provisioning can add procyclicality

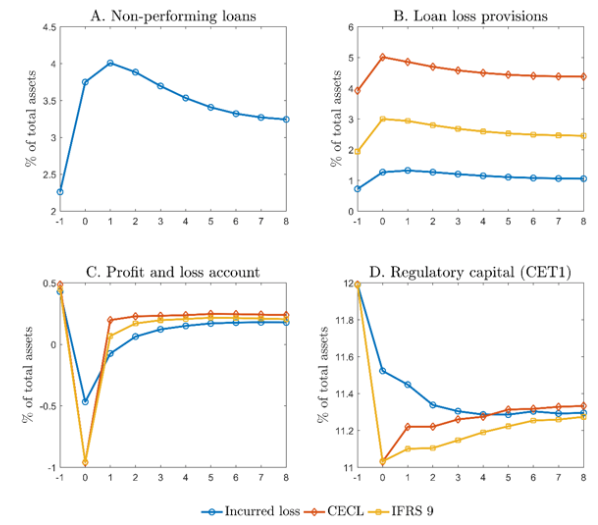

However, as we show in Abad and Suarez (2018), absent the capacity of banks to anticipate adverse shifts in aggregate conditions sufficiently in advance, the upfront recognition of future expected losses may paradoxically imply that, right at the beginning of economic contractions, banks suffer a more abrupt fall in profits and subsequently capital than under the old incurred loss paradigm. Intuitively, the expected loss approach implies having to provision, when the contraction starts, some anticipated credit losses that would only be provisioned as they gradually occur under the incurred loss approach (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Effects of the arrival of a contraction under different provisioning rules

Note: This figure is based on the results in Abad and Suarez (2018) that quantify, under alternative provisioning standards, the impact of the arrival of an average recession on a bank portfolio of European corporate loans and its implications for the profit and loss and regulatory capital (CET1) of the corresponding bank. The horizontal axis represents years after the arrival of a recession.

For banks’ subject to capital requirements and with limited capacity to raise fresh new capital, losing capital may imply contracting their supply of lending, as previously emphasized in the literature on the procyclicality of Basel capital requirements (Kashyap and Stein 2004, Repullo and Suarez 2013). This mechanism is particularly relevant in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic where an unanticipated shock has caused an abrupt contraction in economic activity. The least traumatic absorption will require channelling enough credit and liquidity to the most affected sectors, thus bringing into question the implications of expected loss provisioning in such times.

The quantitative results of our analysis indicate that, for a hypothetical bank fully specialized in European corporate loans, the arrival of an average recession would imply on-impact increases in IFRS 9 and CECL provisions equivalent to about 100 basis points of CET1 (as a fraction of total assets), that is, more than a third of the bank’s fully loaded capital conservation buffer (CCB). This impact is about twice as large as that implied by the previous incurred loss approach.

The COVID-19 crisis calls for preventing the procyclical effects

If the COVID-19 contraction were to cause an impact on foreseeable defaults several times the size of an average recession, the initial impact on bank capital might easily deplete the voluntary and regulatory capital buffers (on top of the minimum requirements) with which banks enter this crisis. Additionally, beyond its initial impact, the uncertainty regarding the depth and duration of the COVID-19 crisis can make banks face higher variability in their provisioning needs (and higher volatility in their available capital) under the new provisioning standards as compared to the old ones.

The sudden and unexpected nature of the pandemic, and the certainty that its implications will be less damaging for the economy if there is plenty of credit flowing towards the affected businesses and households, suggest the desirability of preventing the procyclical damage that the new provisioning standards can cause in this crisis.

In a recent column advising against any change in current provisioning standards, Nicolas Véron argues “there is no perfect accounting thermometer for credit risk in banks’ loan books, but breaking the current thermometer in the midst of a crisis would do far more harm than good.” Fortunately, however, there are ways to neutralize the capital (and likely credit supply) impact of IFRS 9 (or its US companion CECL) without “breaking the thermometer,” that is, without forsaking estimation of the expected credit losses arising out of this crisis or any other in the immediate future, and their reflection in banks’ profit and loss accounts.

No need to break the thermometer: use the transitional arrangements

Such a solution relies on allowing for capital adjustments of the same nature as those that have been applied in the EU in the form of ‘transitional arrangements’ since IFRS 9 was first introduced in 2018. Such arrangements were put in place to smooth away over time the impact on capital and credit of the additional provisioning needs implied by the new standards. Banks were given the option to use them or not.

In essence, the existing transitional arrangements allow banks to write back as available capital as much as 95% of the additional loss absorption implied by the new provisions in 2018, 85% in 2019, 70% in 2020, 50% in 2021, and 25% in 2022. The transition was planned to end in 2023. Under these arrangements, the provisions are made according to the new expected loss paradigm, so there is transparency about banks’ estimates of the expected incoming losses, but part of their impact on a bank’s available capital (CET1) is neutralized.

In our view, guaranteeing that the new standards are not a source of additional procyclicality during the fight against the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic calls for, at the very least, stopping the clock of the transitional arrangements (which in 2020 would still allow banks to write back 70% of the extra provisions). In fact, we think it would make sense to delay the clock all the way back to its 2018 position: allowing banks for a 95% addback until further notice.

To avoid banks’ temptation to enter into games where they signal their strength by opting out of the transitional arrangements, we argue for making the adoption of the modified transitional arrangements mandatory. And to avoid ‘wasting’ the freed capital in distributions, we would expect banks and/or their supervisors to guarantee the freeze of dividends and share repurchases during the standby period, as part of a ‘quid pro quo’ deal. Finally, our proposed measure would come with the announcement that, once this exceptional period is over, the path of the transitional arrangements would be retaken, after proper rescheduling.

In the EU context, with the IFRS 9 transitional arrangements already in place, dictating the freezing or delaying-and-freezing of the transitional clock would involve minor legislative adaptations. This would pose no challenge to the verification of compliance with the rules relative to the status quo (in which such transitional arrangements already exist). From the point of view of preserving the informative value of the accounting statements and the continuity of the costly procedures that are needed to adopt, internally validate, and enforce the new standards, we think our proposal is superior to the alternatives arguing for simply waiving the new standards (Stein et al. 2020) or applying them with additional (and ambiguously defined) flexibility, as was recently recommended by the Bank of England and the ECB.

Afterword

To conclude, while we sympathize with the principle that one should avoid changing the rules of the game in the middle of a match, the nature and severity of the COVID-19 crisis and the foreseen importance of bank credit in coping with it would call for and fully justify the adoption of our easily implementable proposal by the authorities.

References

Abad, J., and J. Suarez (2018), “The Procyclicality of Expected Credit Loss Provisions”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13135.

Financial Stability Forum (2009), “Report of the Financial Stability Forum on Addressing Procyclicality in the Financial System”, April.

Kashyap, A., and J. Stein (2004), “Cyclical implications of the Basel II capital standards”, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Economic Perspectives, 1st Quarter, pp. 18-31.

Repullo, R., and J. Suarez (2013), “The procyclical effects of bank capital regulation”, Review of Financial Studies 26, pp. 452-490.

Stein, J. C., R. Greenwood, S. G. Hanson, and A. Sunderam (2020), “How the Fed Can Use its Bank Prudential Authorities to Support the Economy and the Flow of Credit”, Harvard University, March.

Endnotes

1 See https://www.bruegel.org/2020/03/banks-in-pandemic-turmoil-capital-relief-is-welcome-supervisory-forbearance-is-not/

2 See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R2395&from=EN

3 See https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/news/2020/march/boe-announces-supervisory-and-prudential-policy-measures-to-address-the-challenges-of-covid-19 and https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2020/html/ssm.pr200320_FAQs~a4ac38e3ef.en.html