This crisis has the potential to hit women harder than any almost other in recent memory. From a medical perspective, early evidence seems to suggest that it is men who are most vulnerable to the virus, particularly in terms of fatalities (Global Health 50-50 2020). This is, of course, hugely concerning.

However, when it comes to the wider social and economic fallout from the crisis, in many ways it is women who are on the frontline. As has been widely reported in recent weeks, women are often over represented among essential services workers. Women make up two-thirds of the health workforce worldwide, for instance, including 85% of nurses and midwives (Boniol et al. 2019); across OECD countries, they also account for 90% of long-term care workers (OECD 2020). At home, women are shouldering much of the additional unpaid work caused by school and childcare closures, adding a third leg to the double shift many women already put in. And reports emerging from a number of countries suggest escalating risks of domestic violence, confirming a pattern seen in past lockdown and confinement situations (UNDP 2015).

Just to add to all this, this crisis, unlike most previous crises, has the potential to do disproportionate damage to women’s jobs and incomes. Across almost all OECD countries (and many others outside the OECD), women have made enormous strides in the labour market in the past few decades. This crisis is putting that under threat.

This time could be different

Evidence from past economic crises suggests that recessions often affect men’s and women’s employment differently, with men historically the biggest losers (Rubery and Rafferty 2013). The 2008 financial crisis, for instance, was to some extent a ‘male’ crisis: especially in the early years, job losses were much greater in male-dominated sectors of the economy (notably construction and manufacturing), with women’s working hours actually increasing (Sahin, Song and Hobijn 2012 OECD 2012). Evidence from several other developed-world economic crises point in a similar direction, with women losing less, partly because they are less likely to be employed in cyclical industries (Hoynes et al. 2012).

This time could well be different. This crisis is different in nature to previous ones; it is not just an economic crisis, but also a health and social crisis. Many women are already struggling to make it to work at all, given the need for at least one parent to stay home due to school or childcare facility closure. The lucky ones might be able to use teleworking as a partial and temporary solution.

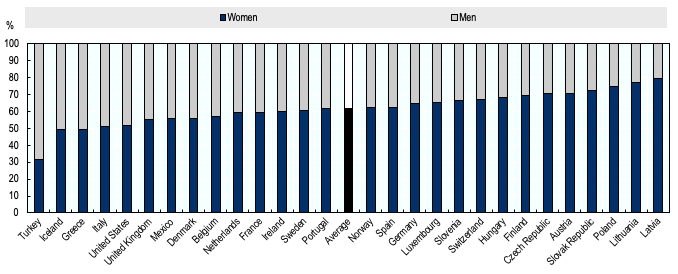

Beyond this, the confinement and distancing measures being put in place around the world are threatening to shatter several female-dominated industries. At least in the short term, jobs that rely on travel and on physical interaction with customers are clearly vulnerable. This includes air travel, tourism, retail activities, accommodation services (e.g. hotels), and food and beverage service activities (e.g. cafés, restaurants, and catering). Many of these industries are major employers of women: on average across OECD countries, women make up roughly 47% of employment in the air transport industry, 53% in food and beverage services, and 60% in accommodation services (ILO 2020). In the retail sector, on average, 62% of workers are women, rising to 75% or more in Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (Figure 1).

Some female-dominated industries further down the supply chain will also be hit hard, quickly. One example is the garment manufacturing industry, which is facing heavy disruption from both the supply side (e.g. from confinement measures forcing factory closures) and the demand side (e.g. with the forced closure of retail stores leading to a fall in orders). Women are heavily over-represented in this industry – by some measures, as many of three-quarters of worldwide garment industry workers are women (OECD, 2020[10]). And, given the global distribution of garment supply chains, it is women in developing and emerging economies who will be hit hardest.

The longer-term impact on employment and the distribution of job loss is, at this stage, much harder to predict; a lot depends on the severity and duration of containment measures and the depth and breadth of the economic contraction. As confinement measures expand and supply-chain disruption begins to bite, it is likely that the economic impact will widen across sectors and industries. Indeed, according to early reports, many countries are already seeing a drop in construction and manufacturing activity (ILO 2020). A broader economic contraction may well involve job loss in both male- and female-dominated sectors of the economy.

Figure 1 Women make up a large share of employment in many of the industries most immediately affected by COVID 19, such as retail

Distribution of employment in retail activities, by sex, 2018

Note: Data refer to women's share of employment in ISIC Rev 4. category 47 (Retail trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles)

Source: OECD calculations based on data from ILO ILOSTAT, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

For some women workers, the public sector may offer some protection, at least in the short term. Across the OECD, women make up a disproportionate share of public sector employees: on average, just over 60% of public sector workers are women, rising to roughly 70% in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden (OECD, 2019[12]). While demands on many of these workers will be heavy – especially for workers in public health and social care – these jobs should at least offer relative security in the coming months, as governments seek to maintain demand and deal with the most acute health and social care aspects of the crisis.

Income loss hurts women more

Regardless of the gendered impact of job and business loss, we know that women are often more vulnerable than men to any sharp loss of income. Across OECD countries, women’s incomes are, on average, lower than men’s, and their poverty rates are higher (OECD 2020). Women also often hold less wealth than men, for a variety of reasons (Sierminska et al. 2010, Schneebaum et al. 2018). And because women tend to hold greater care and domestic responsibilities than men, it is often more difficult for women to find alternative employment and income streams (such as piecemeal work) following lay-off.

Single parents, many of whom are women, are likely to be in a particularly vulnerable position. Reliance on a single income means that job loss can be critical for single parent families, especially where public income support is weak or slow to react. Evidence from the 2008 financial crisis suggests that, in many countries, children in single-parent families were hit much harder by the recession than children in two parent families, not only in terms of income, but also in terms of access to essential material goods and activities such as adequate nutrition and an adequately warm home (Chzhen 2014).

Policy responses to COVID-19 must take women into account

Governments are facing a huge challenge in managing to the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. There are many different groups that are in urgent need of support – not least the elderly. But as governments look to construct their policy responses, it is crucial that they do not ignore the impact the crisis can, is, and will have on women.

For many women, one of the most pressing needs is short-term help with the additional care responsibilities brought about by school and childcare centre closure. Several OECD governments have already taken steps in this direction. Some countries (e.g. Austria, Italy, Portugal, and Slovenia) have introduced a statutory right to (partially) paid leave for parents with children below a certain age, while others (e.g. France) have stated that stated that parents impacted by school closure and/or self-isolation will be entitled to paid sick leave if no alternative care or work (e.g. teleworking) arrangements can be found. In a number of countries (e.g. Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK), school are closed but premises remain open, with a skeleton staff, in order to care for the children of essential service workers.

Given the potential vulnerability of women’s jobs, reinforcing unemployment benefits and other income supports is also important. Even before the crisis, many OECD countries were exploring how to shore up access to out-of-work benefits in the context of the changing world of work; several have since introduced emergency measures aimed at supporting people who have lost their jobs or incomes. For instance, many countries have taken steps to extend and/or increase the generosity of out-of-work benefits (e.g. Australia, Canada, Ireland, Sweden, the UK, and the US). A number of others have introduced special programmes for the self-employed who may not otherwise be covered (e.g. Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Lithuania, and Poland). Some countries (e.g. Australia, the US) have introduced one-off emergency cash payments, sometimes as a universal benefit (e.g. the US).

More fundamentally, all economic and social policy responses to the crisis must be embedded in broader efforts to mainstream gender. In the short run, this means, wherever possible, applying a gender lens to emergency policy measures. In the longer run, it means governments having in place a well-functioning system of gender mainstreaming, relying on ready access to gender-disaggregated evidence in all sectors and capacities. Governments must ensure that all policy and structural adjustments aimed at recovery go through robust gender and intersectional analysis, so that differential effects on women and men can be assessed – and planned for.

References

Boniol, M et al. (2019), “Gender equity in the health workforce: Analysis of 104 countries”, Health Workforce Working Paper, No. 1, World Health Organization.

Chzhen, Y (2014), “Child Poverty and Material Deprivation in the European Union During the Great Recession”, UNICEF Innocenti Office of Research Working Paper, No. WP-2014-No. 06, UN, New York.

Global Health 50-50 (2020), Sex, gender and COVID-19.

Hoynes, H., D. Miller and J. Schaller (2012), “Who Suffers During Recessions?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 26(3): 27-48.

ILO (2020), COVID-19 and the world of work: Impact and policy responses.

ILO (2020), ILOSTAT Database.

OECD (2020), OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD).

OECD (2020), Tackling violence and harassment in textiles, clothing, leather and footwear: Implications of the new ILO Convention No. 190: Background Note to the OECD Garment Forum 2020, OECD.

OECD (2020), Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2012), Closing the Gender Gap: Act Now, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Rubery, J. and A. Rafferty (2013), “Women and recession revisited”, Work, employment and society 27(3).

Sahin, A., J. Song and B. Hobijn (2012), “The Unemployment Gender Gap During the 2007 Recession”, SSRN Electronic Journal.

Schneebaum, A. et al. (2018), “The Gender Wealth Gap Across European Countries”, Review of Income and Wealth, pp. 295-331.

Sierminska, E, J Frick and M Grabka (2010), “Examining the gender wealth gap”, Oxford Economic Papers 62(4): 669-690.

UNDP (2015), Assessing Sexual and Gender Based Violence during the Ebola Crisis in Sierra Leone, UNDP.