As COVID-19 rapidly emerged through early 2020, many governments introduced job retention schemes (OECD 2020). By maintaining the connection between workers and firms, such schemes aimed to support household incomes, reduce uncertainty, and temporarily shield firm-specific capital to bridge pre- and post-pandemic economies (Lowe 2020).

If pandemic policy aimed to engineer an economic hibernation, then a key risk was zombification, where job retention schemes delay the restructuring of low-productivity firms that would have otherwise downsized or exited. Timely evidence on this question is limited but tends to support the idea that reallocation was productivity-enhancing (Cros et al. 2021, Bloom et al. 2021) and that zombie firms did not disproportionately tap crisis support (Cœuré 2021) during the pandemic.

Against this backdrop, our recent paper explores the pandemic’s consequences for productivity-enhancing reallocation and the contribution of JobKeeper, Australia’s job retention scheme (Andrews et al. 2021). We use high-frequency administrative tax data on firm-level employment from Single Touch Payroll merged with business register data, which is highly representative of the Australian economy.

We find evidence on the allocative effects of the pandemic-induced recession almost five years earlier compared to the Great Recession (Foster et al. 2014). This can help inform Australian economic policymaking in real-time (Kehoe 2021).

COVID-19 and productivity in the Land Down Under

We estimate how firm-level employment changes and exit since the onset of the pandemic are correlated with pre-shock firm labour productivity, within state-industry cells and firm size and age classes. This approach follows the canonical models of firm dynamics (Hopenhayn 1992, Hopenhayn and Rogerson 1993), the literature on adjustment costs for employment dynamics (Cooper et al. 2007), and the wealth of empirical evidence that high (or low) productivity firms are more likely to expand (or contract/exit) (e.g. Decker et al. 2020, Andrews and Hansell 2021).

While the overall rate of job turnover fell during the pandemic, reallocation remained connected to firm productivity. Between March and December 2020, high- and low-productivity firms – defined as one standard deviation above/below the industry productivity mean – had an implied difference in employment growth of 6.5 percentage points.

Similarly, a low productivity firm was on average 3.75 percentage points more likely to exit than a high-productivity firm. This link was stronger (i) for small firms, which were more exposed to the shock; (ii) in hard-hit sectors (i.e. hospitality, arts and recreation); and (iii) in Victoria during the pandemic’s second wave (July–August 2020).

These cleansing dynamics are consistent with the analysis of cloud accounting data for Australia (Andrews, Charlton and Moore, 2021) and evidence from France (Cros et al. 2021). They run counter to concerns about zombification, which hampered productivity growth in Southern Europe following the financial crisis (Adalet McGowan et al. 2018).

Job retention schemes played a nuanced role

That the reallocation–productivity link remained intact is surprising, given the scale of the JobKeeper scheme – the largest one-off fiscal measure in Australia’s history – which supported more than 3.8 million individuals and one million organisations. JobKeeper provided broad-based crisis support from April to September 2020 (JobKeeper 1.0) but was then phased out and firms had to re-apply in October and December 2020 (JobKeeper 2.0) until the scheme’s end in March 2021.

Over the life of the scheme, productivity-enhancing reallocation was on average stronger in local labour markets that had a higher proportion of the workforce in receipt of JobKeeper, even after controlling for the size of the economic shock. These results are consistent with the fact that JobKeeper 1.0 disproportionately shielded productive but financially fragile firms – a pivotal group whose premature shakeout could be scarring.

Thus, the COVID-19 shock distorted market selection, and policy may have corrected this distortion. In other words, policy support may have not been as unproductively distributed as feared (Bighelli et al. 2021).

But as the economy recovered, the scheme grew more distortive: JobKeeper 2.0 (from October 2020) was more likely to support low-productivity firms. In late 2020, there was hardly any productivity-enhancing labour reallocation in local labour markets where JobKeeper 2.0 remained pervasive.

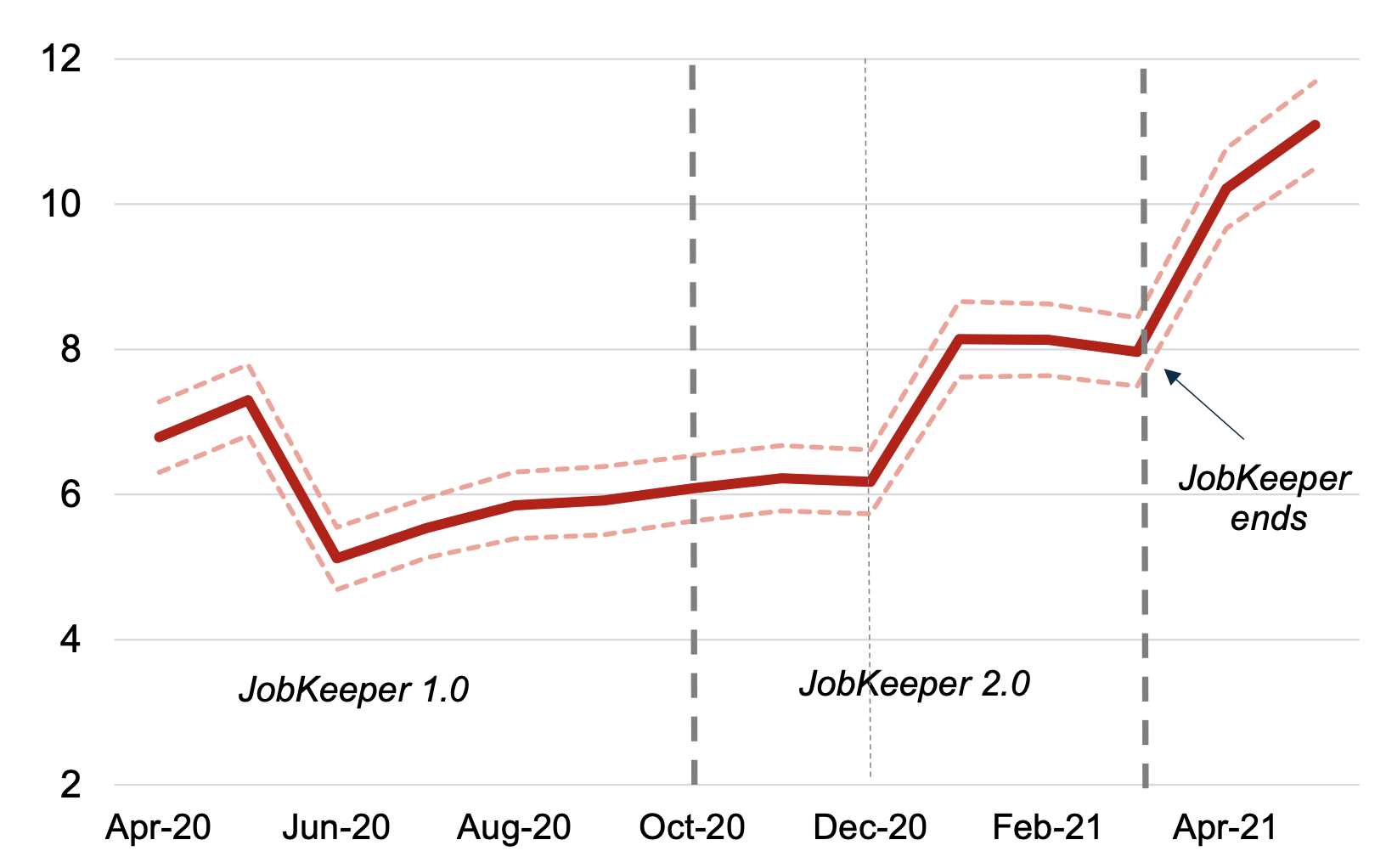

By contrast, where a large portion of the workforce exited the scheme, more labour flowed towards high-productivity firms, and there was a surge in productivity-enhancing reallocation when the scheme ultimately ended (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Implied difference in employment growth between high- and low-productivity firms

Estimated monthly profile (percentage pts): March 2020 to May 2021

Notes: The thick line shows the estimated difference in employment growth between a high-productivity firm (with LP one standard deviation above the industry mean) and a low-productivity firm (with LP one standard deviation below the industry mean). Employment growth is the cumulative change at each month relative to March 2020. The dashed line denotes the 95% confidence intervals. Source: Andrews, Bahar and Hambur (2021).

Aggregate implications

The greater resilience of high-productivity firms is significant, given the scarring effects that would arise from an indiscriminate shakeout of such firms. We estimate that it raised aggregate labour productivity by 4.25% to 5.5%, relative to a counterfactual where the pandemic severed the reallocation-productivity link. Around half of this aggregate gain can be accounted for by the introduction of JobKeeper 1.0, and specifically its tendency to shield more productive (and financially fragile) firms.

But had policymakers not phased out JobKeeper, aggregate productivity could have been 2% lower, owing to the rising allocative distortions. The removal of JobKeeper thus appears justified – on productivity grounds at least – especially given the economic recovery.

Conclusion

Policies aimed to preserve links between workers and firms during a crisis can potentially protect workers from scarring without significantly distorting the economy’s firm dynamics. While this suggests that concerns that job retention schemes would lead to zombification were overplayed, our results also demonstrate that there is a fine line between such policies being supportive and distortive. It underscores that crisis policies must be truly temporary and their design must evolve as economic conditions change.

References

Adalet McGowan, M, D Andrews and V Millot (2018), “The walking dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries”, Economic Policy 33(96): 685–736.

Andrews, D, E Bahar and J Hambur (2021), “The COVID-19 shock and productivity-enhancing reallocation in Australia: Real-time evidence from Single Touch Payroll”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1677.

Andrews, D, A Charlton and A Moore (2021), “COVID-19, productivity and reallocation: Timely evidence from three OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1676.

Andrews, D, and D Hansell (2021), “Productivity-enhancing labour reallocation in Australia”, Economic Record 97(317): 157–69.

Bighelli, T, T Lalinsky and F di Mauro (2021), “Covid-19 government support may have not been as unproductively distributed as feared“, VoxEU.org, 19 August.

Bloom, N, P Bunn, P Mizen, P Smietanka and G Thwaites (2021), “The impact of Covid-19 on productivity“, VoxEU.org, 18 January.

Cooper, R, J Haltiwanger and J Willis (2007), “Search frictions: Matching aggregate and establishment observations”, Journal of Monetary Economics 54(suppl.): 56–78.

Cœuré, B (2021), “What 3.5 million French firms can tell us about the efficiency of Covid-19 support measures“, VoxEU.org, 8 September.

Cros, M, A, Epaulard and P Martin (2021), “Will Schumpeter catch COVID-19? Evidence from France“, VoxEU.org, 4 March.

Decker, R, J Haltiwanger, R S Jarmin and J Miranda (2020), “Changing business dynamism and productivity: Shocks vs. responsiveness”, American Economic Review 110(12): 3952–90.

Foster, L, C Grim and J Haltiwanger (2014), “Reallocation in the Great Recession: Cleansing or not?”, NBER Working Paper 20427.

Hopenhayn, H (1992), “Entry, exit, and firm dynamics in long run equilibrium”, Econometrica 60(5): 1127–50.

Hopenhayn, H, and R Rogerson (1993), “Job turnover and policy evaluation: A general equilibrium analysis”, Journal of Political Economy 101(5): 915–38.

Kehoe, J (2021), “Why JobKeeper must not return”, Australian Financial Review, 28 July.

Lowe, P (2020), “Responding to the economic and financial impact of COVID-19 – Sydney”, speech, Reserve Bank of Australia, 19 March.

OECD (2020), Job retention schemes during the COVID-19 lockdown and beyond, OECD Policy Response to Coronavirus (COVID-19), Paris: OECD, 12 October.