A forceful policy reaction is the key to limiting the damage from the COVID-19 economic crisis and putting the global economy in the best possible position to recover (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020).

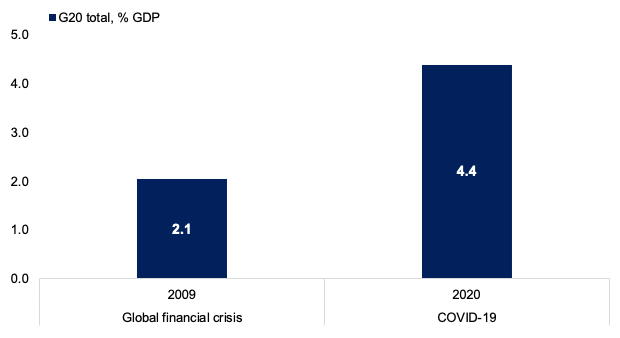

A cursory glance at headline measures implies that policy is rising to the challenge: the IMF note that global fiscal support – broadly defined – is around $9 trillion, while revenue and spending measures alone are more than twice that undertaken in 2009 (Figure 1) (Battersby et al. 2020). In addition, central banks’ balance sheets are moving quickly into uncharted territory. But judging whether the plethora of conventional and unconventional fiscal and monetary policies is sufficient requires a view on the scale and nature of the shock, and also the composition across countries. Only time will tell whether policy makers have really done enough.

Figure 1 Current ‘above-the-line’ fiscal policy more than twice that of the Global Crisis

Sources: IMF staff estimates (as of 13 May 2020).

Note: includes above-the-line spending and revenue measures only, weighted by GDP in PPP-adjusted current US dollars.

Understanding the policy reaction of the US and China – the world’s largest economies – is critical. The US plays a key role in driving the global financial cycle (Rey 2013), while China’s rapid integration into the global economy has made it a major driver of global growth. Indeed, this was particularly the case following China’s aggressive policy reaction after the Global Crisis, and the authorities have implemented wide ranging measures following the corona-shock (Huang et al. 2020).

Judging the overall policy stance in China at any given point in time is difficult due to the vast number of levers which are being pulled. Monetary policy operates through numerous interest rates – and sometimes quantitative guidance – while the fiscal stance is often quite opaque, for example.

Moreover, as China’s economy has evolved so has its policy framework and the tools used within it. Thus, making an assessment of how policy has evolved over time requires judgement on which measures matter and when. As we discuss later, there are strong reasons to believe the efficacy of policy has been changing over time too.

Financial conditions can provide one gauge of the policy stance and transmission

Examining both what the authorities appear to be doing and the results is one way to assess how conventional and unconventional policy levers are being operated. Financial conditions therefore provide one useful gauge of the policy stance, its transmission to financial markets, and ultimately the effects on the real economy. Hatzius et al. (2010) provide a useful summary of the literature.

The development of a financial conditions index (FCI) which summarises not just the broad array of policy tools at the hands of the Peoples’ Bank of China (PBOC), but also other factors – such as bond yields, money, credit, risk premia, volatility, and FX – into an easily interpretable time series allows for an easy tracking of financial conditions in real-time.

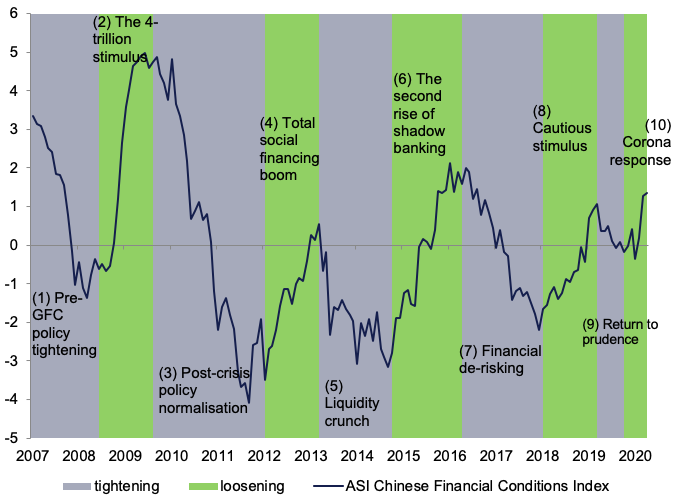

The resulting China FCI (Watt et al. 2019) follows the broad contours of the Chinese policy landscape. As shown in Figure 2, financial conditions (i) became exceptionally loose after the global crisis; (ii) eased notably again in 2015/16, as market fears of a China hard landing intensified; (iii) tightened in 2017, reflecting the authorities’ de-risking campaign; and (iv) in 2020 have been becoming more accommodative in response to the coronavirus shock.

Figure 2 History of China’s financial cycle

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments, Bloomberg and Haver (as of April 2020).

Note: Grey shading highlights a period of tightening financial conditions with the index falling and green shading highlights a period of loosening financial conditions with the index increasing.

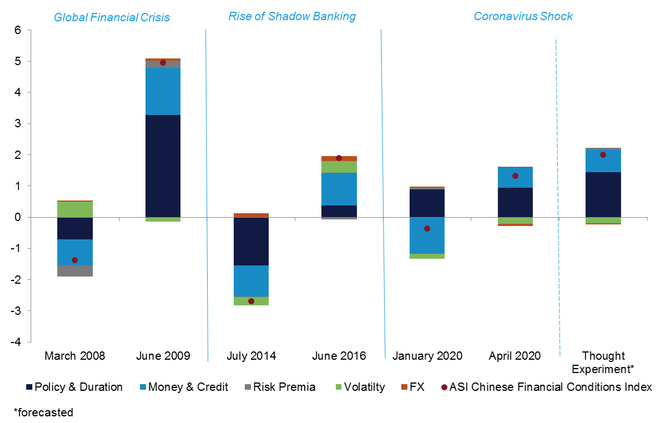

As well as tracking the financial cycle over time, financial conditions can be broken down by their contributions to draw out how the policy reaction has differed at key times. Figure 3 shows that the reaction to the coronavirus shock differs in several notable ways to the previous easing episodes. Specifically, (i) financial conditions were much closer to neutral ahead of the shock, reflecting a balance between loose policy and duration factors (such as government bond yields) and relatively tight money and credit; and (ii) the easing to date largely reflects money and credit moving from tight to loose, but the easing from these factors remains much smaller than in past episodes, consistent with the authorities’ continued pursuit of de-risking and medium-term financial stability.

Figure 3 Changing contributions to financial conditions

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments, Bloomberg and Haver (as of April 2020).

Financial conditions could become as accommodative as that seen in 2016

Thus far, the policy reaction in China – as captured by the FCI – appears relatively restrained compared to past episodes, but how much more easing could be on its way?

As a thought experiment we consider how financial conditions could evolve should the components evolve roughly in line with the views of the ASI Research Institute. In particular, we suppose some further policy easing (-20 basis point cuts to the seven-day reverse repo and medium term lending facility, with -100 basis point to the RRR), allow yields to fall further, let the monetary aggregates accelerate somewhat, but keep the credit impulse neutral. The contribution of FX has historically been small relative to other factors. Continued tensions between the US and China suggest that FX is unlikely to contribute to more accommodation; hence, we assume this is unchanged.

Under these (plausible, albeit illustrative) assumptions, financial conditions could rival the levels seen in 2016, driven by a further easing in policy and duration factors (Figure 3). The change in the FCI is much less marked than previous easing episodes, given the starting position.

Fiscal policy and credit growth help complete the picture

Some aspects of Chinese fiscal policy and credit growth will be captured by the CFCI shown above: the credit impulse is a direct measure, while monetary aggregates are indirect. But one can also compare how fiscal policy is changing and the magnitudes of credit growth to obtain a more holistic picture of the Chinese policy stance.

There is an active debate as to where the fiscal perimeter should be drawn (Mano and Stokoe 2017). A large proportion of Chinese fiscal policy is conducted off balance sheet and how such items are evolving is particularly unclear in real time. Relatedly, credit and off-balance-sheet items sometimes blur, so it is important to ensure that stimulus is neither missed nor double-counted.

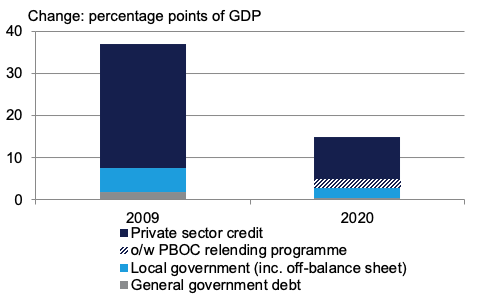

Figure 4 shows our best guess as to how supportive Chinese fiscal and credit policy will be in 2020 in response to the coronavirus shock, compared to the reaction following the Global Crisis. As shown, the response has been much more restrained, perhaps only 40% of that in 2009. This is the opposite of the reaction in many other countries, for example the fiscal response in the US is much larger now compared to the Global Crisis.

Figure 4 Chinese policy response via credit and fiscal channels is likely less than half that seen in the Global Crisis

Source: ASIRI, BIS

What does this mean for China and the rest of the world?

The effects on China and the rest of the world will obviously be a function of the magnitude and composition of policy changes (financial conditions, credit, fiscal) and the pass-through of each on the economy – not just in China, but across all countries.

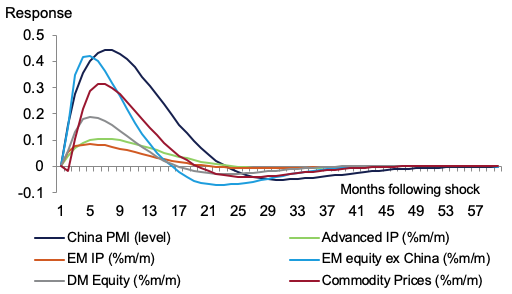

Extending the analysis of Lodge and Soudan (2019), we first quantify the effects of changes in Chinese financial conditions on domestic macroeconomic variables, and the spillovers to foreign economies and financial markets within a Bayesian VAR (BVAR), finding evidence that emerging markets are impacted more than advanced economies (Figure 5). Please see Table 1 for a full list of the variables in the BVAR, and for more detail on the methodology please see Watt et al. (2019).

Figure 5 Impact of a one-unit shock to Chinese financial conditions

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments, Bloomberg and Haver (as of October 2019).

These results suggest that the recent loosening in financial conditions should support activity over the next six to nine months, but it will only be at best half that seen in 2016 and a third of that after the Global Crisis given the relative change in financial conditions thus far.

This suggests that China is playing a relatively smaller role supporting the global economy now, compared to the Global Crisis. But other countries – such as the US – are doing more than during the Global Crisis. Indeed, the variance decomposition in our model shows the US drives more of the variables in the system than the Chinese financial conditions index.

Of course, the coronavirus has created an unprecedented shock on both supply and demand side of the modern global economy which could influence policy transmission domestically and change the spillovers. Policy in China and the US (similar to elsewhere) is attempting to avoid a much worse outcome, helping businesses and firms survive until the supply disruption fades. As such, policy is underpinning solvency rather than providing a significant boost to growth, and this could imply smaller multipliers and spillovers.

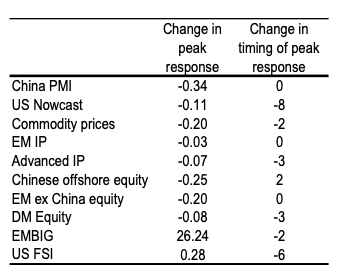

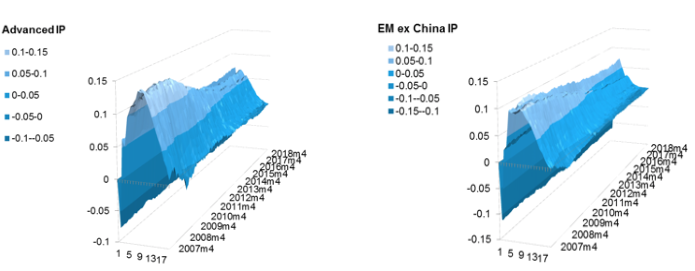

In China’s case, we already have reason to believe that policy efficacy has been falling, in part reflecting the drag from high leverage (Chen et al. 2017). Indeed, our research using time-varying parameters suggests that responses to changes in financial conditions have been declining over time, although the peak response comes sooner (Table 1, Figure 6).

Table 1 The efficacy of policy appears to have fallen over time

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments, Bloomberg and Haver (as of October 2019).

Note: Table shows the change in the magnitude of the peak response as measured in June 2009 and May 2016 as well as the change in the timing of the peak i.e. -8 implies that the peak response in 2016 was eight months earlier than in 2009.

Figure 6 Time-varying impulse responses for external activity

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments.

Note: charts show the time-varying response of activity variables. The x-axis shows the number of months following the initial shock; the y-axis shows the magnitude of the response; the z-axis shows the period in which the response was measured.

Conclusion

It is possible that Chinese financial conditions could become as accommodative as the levels seen in 2016, but the change in financial conditions suggests it will only impart stimulus of a third of that after the Global Crisis. And considering the policy stance by examining fiscal and credit policy paints a similar picture: these policy levers are at best only 40% of that deployed during the Global Crisis. Indeed, China’s policy reaction to the corona-shock and Global Crisis has been a near mirror image to that undertaken by other countries (who have reacted more aggressively to the former than the latter).

Additionally, the Chinese economy may be twice the size it was during the Global Crisis, but the more limited policy reaction, evidence of falling multipliers, and the nature of the corona-shock itself suggest that Chinese policy will not help to drive the global economy forward as it did after the Global Crisis. And whilst other economies appear to be doing more (at face value) than during the Global Crisis, the scale and nature of the corona-shock make it hard to judge whether policy makers are really doing enough.

References

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (2020), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Battersby, B, R Lam and E Ture (2020), “Tracking the $9 Trillion Global Fiscal Support to Fight COVID-19”, IMF Blog, 20 May.

Chen, S, L Ratnovski and P H Tsai (2017) “Credit and Fiscal Multipliers in China”, IMF Working Papers, Volume 273.

Hatzius, J, P Hooper, F S Mishkin, K L Schoenholtz and M W Watson (2010), “Financial Conditions Indexes: A Fresh Look After the Financial Crisis”, NBER Working Paper Series, Volume 16150.

Huang, Y, C Lin, P Wang and Z Xu (2020), “Saving China from the coronavirus and economic meltdown: Experiences and lessons”, VoxEU.org, 23 March.

Lodge, D and M Soudan (2019), “Credit, financial conditions and the business cycle in China”, ECB Working Paper Series, Volume 2244.

Mano, R and P Stokoe (2017), “Reassessing the Perimeter of Government Accounts in China”, IMF Working Paper WP/17/272, Asia Pacific Department.

Rey, H (2013), “Dilemma not Trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence”, Presented at the Jackson Hole Symposium, August 2013.

Watt, A, C Martinez, J Lawson and R Fu (2019), “Decoding the Chinese financial cycle and its effects on the global economy and markets”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14065.