The financial crisis of 2008–09 has reignited interest in understanding the crucial roles money and credit play in the creation, propagation, and amplification of economic shocks. Such research on the importance of financial structure promises to reopen a number of fundamental fault lines in modern macroeconomic thinking.

Economic history has an important role to play here, as a better empirical understanding can guide us toward the development of more useful economic reasoning. Deductive economics, pure theory detached from evidence, now confronts inductive economics, a careful empirical science grappling with “facts on the ground”, in the words of Barry Eichengreen (2009).

Two eras of finance capitalism

Our recent research (Schularick and Taylor 2009) steps back and asks three comparative questions about money, credit, and the macroeconomy in the long run:

- How did money and credit aggregates develop in the long run?

- How do monetary and credit aggregates behave in the years following a financial crisis?

- What role do credit and money play as a cause of financial crises?

To that end, we have assembled a new dataset on money and credit, aligned with various macroeconomic indicators, covering 12 developed countries and almost 140 years from 1870 to 2008, with special attention to crisis episodes. Our paper therefore sits in a new strand of literature that uses historical data to study macroeconomic rare events (Almunia et al. 2009a,b, Barro 2009, Reinhart and Rogoff 2009).

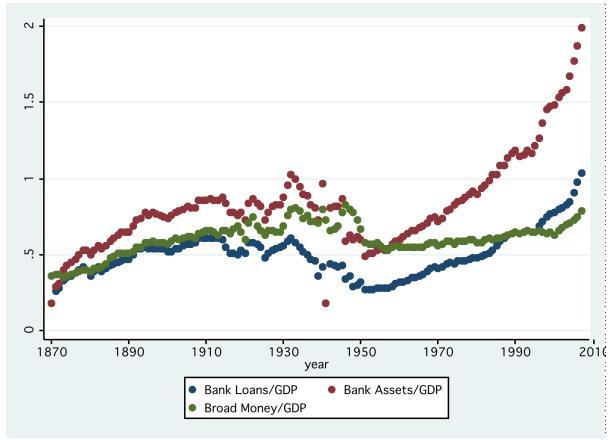

Our new dataset allows us to establish a number of important stylised facts about what we shall refer to as “two eras of finance capitalism”. Figure 1 displays average year effects from 1870 to 2007 for some variables of interest, so as to estimate average global trends in money and credit aggregates.

Figure 1. Global average leverage, 1870–2007 (year effects)

Note: The countries in the sample are Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US.

The first era runs from 1870 to 1939. Our gold-standard ancestors lived in an age where aggregate credit was closely tied to aggregate money. In this era, money and credit were volatile but, over the long run, they maintained a roughly stable relationship with each other and with the size of the economy measured by GDP. The only exception to this rule was the Great Depression period; in the 1930s, money and credit aggregates collapsed relative to GDP. This stable relationship between money and credit broke down after the Great Depression and WW2, as a new secular trend took hold that carried on until today’s crisis. But prior to 1930, broad money and loans had been stable at about 50%–60% of GDP for decades, and bank assets stood at about 80%–90% of GDP.

In this second era, money and credit began a long postwar recovery, trending up rapidly and eventually surpassing their pre-1940 levels compared to GDP by the 1970s. This could be seen as a secular recovery by the financial system from the massive destruction suffered in the 1930s. But the process did not end there. In addition, credit itself then started to decouple from broad money and grew rapidly, via a combination of increased leverage and augmented funding via nonmonetary liabilities of banks. In recent decades, we have been living in a different world, where financial innovation and regulatory ease have permitted the credit system to increasingly delink from monetary aggregates, resulting in an unprecedented expansion in the role of credit in the macroeconomy. By 2007, the typical level of broad money had risen to about 70% of GDP, but bank loans exceeded 100% and bank assets were over 200%.

In a next step, we look at the behaviour of money and credit aggregates in the years following a financial crisis. More precisely, we study the co-evolution of money and credit aggregates and real economic activity in the five-year window following a financial crisis event, using a set of event definitions based on documentary descriptions of banking crises in Bordo et al. (2001) and Reinhart and Rogoff (2009). Our results confirm our conjecture of dramatically different crisis dynamics before and after WW2.

In post-1945 crises, central banks have strongly supported money growth, and crises have not been accompanied by a collapse of broad money. Whereas financial crisis led to a "deleveraging" of the economy in earlier times, policy actions in the postwar period have effectively prevented episodes of marked balance sheet shrinkage, as Figure 2 illustrates. The bottom line is that the lessons of the Great Depression, once learned, were put into practice. After 1945, financial crises were fought with more aggressive monetary policy responses, banking systems imploded neither so frequently (at least before 1980) nor as dramatically, and deflation was avoided. In the previous era, financial crises led to contractions of the money supply and deflationary pressures, relative to trend, but this is no longer true (this result is not driven by the particular episode of the Great Depression).

Figure 2. Response of aggregates after financial crises

However, on the real economic side, a striking result is that the economic impact of financial crises is no more muted in the postwar era than in the prewar era. It seems that postwar policy activism was “successful” in preventing financial deleveraging but not in reducing the output costs. A cynic might conclude that central banks were successful in bailing out finance but failed to protect the real economy. Of course the obvious caveat here is the nature of the counterfactual – given the much larger financial system we have today (the first stylised fact above), the real effects of the postwar regime could take the form of preventing the potentially even larger real output losses that could be realised in today’s more heavily financialised economies without such policies. And yet it may be plausibly argued that the postwar ascent (especially since the 1970s) of a regime of fiat-money-plus-lender-of-last-resort could have also encouraged the expansion of credit to occur. Aiming to cushion the real economic effects of financial crises, policymakers have effectively prevented the periodic deleveraging of the financial sector seen in the olden days, resulting in the virtually uninterrupted growth of leverage we saw up until 2008.

Finally, we investigate what role the financial system itself plays in generating economic instability. Scholars such as Minsky (1977) and Kindleberger (1978) have argued that the financial system itself is prone to generate economic instability through endogenous credit booms. In their view, the credit system was not merely a propagator of shocks hitting the economy as in the standard financial accelerator model – it often was the shock. Policymakers paid little heed to these views during the recent boom, with the few notable exceptions being largely ignored (e.g., Borio and White 2003).

Our empirical analysis lends considerable support to the Minsky-Kindleberger view of financial crises as "credit booms gone wrong" (Eichengreen and Mitchener, 2003). The credit system seems all too capable of creating its very own shocks, judged by how successful past credit growth performs as a predictor of financial crises. Past credit growth spectacularly improves the forecasting power of an early warning banking crisis model in our data. Using long-run historical data, the growth rate of lending emerges as the single best predictor of future financial instability, a result which is robust to the inclusion of various other nominal and real variables. Moreover, credit outperforms other possible measures such as broad money by some margin. The result also holds true in an out-of-sample test running forward recursively from the 1980s. In light of the structural changes of the financial system discussed above, this comes as no surprise.

Long-run historical evidence therefore suggests that credit has an important role to play in central bank policy. Its exact role remains open to debate. After their recent misjudgements, central banks should clearly pay some attention to credit aggregates and not confine themselves simply to following targeting rules based on output and inflation. However, whether they should also build credit signals into interest-rate policy or develop other instruments to curb excessive leverage remains an unresolved issue.

Not all of this might sound surprising to financial historians who have pointed for a long time to recurrent episodes of financial sector-driven instability in modern economies. But we are hopeful that some of the evidence we have assembled will inform new avenues in economic research into the role of credit in the macroeconomy.

References

Almunia, Miguel, Agustín S. Bénétrix, Barry Eichengreen, Kevin H. O’Rourke, and Gisela Rua (2009a), “From Great Depression to Great Credit Crisis: Similarities, Differences and Lessons”, Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Almunia, Miguel, Agustín S. Bénétrix, Barry Eichengreen, Kevin H. O’Rourke, and Gisela Rua (2009b), “The effectiveness of fiscal and monetary stimulus in depressions”, VoxEU.org, 18 November.

Barro, Robert J. (2009), “Rare Disasters, Asset Prices, and Welfare Costs”, American Economic Review 99(1): 243–64.

Bordo, Michael, Barry Eichengreen, Daniela Klingebiel, and Maria Soledad Martinez-Peria (2001), “Is the Crisis Problem Growing More Severe?” Economic Policy 16(32): 51–82.

Borio, Claudio, and William R. White (2003), “Whither Monetary and Financial Stability: The Implications of Evolving Policy Regimes”, Proceedings, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp. 131–211.

Eichengreen, Barry (2009), “The Last Temptation of Risk”, The National Interest (May/ June): 8–14.

Eichengreen, Barry, and Kris J. Mitchener (2003), “The Great Depression as a Credit Boom Gone Wrong”, BIS Working Paper No. 137, September.

Kindleberger, Charles P. (1978), Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. New York: Basic Books.

Minsky, Hyman P. (1977), “The Financial Instability Hypothesis: an Interpretation of Keynes and Alternative to Standard Theory”, Challenge (March-April): 20–27.

Schularick, Moritz, and Alan M. Taylor (2009), “Credit Booms Gone Bust: Monetary Policy, Leverage Cycles and Financial Crises, 1870–2008”, NBER Working Paper 15512.