Following the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, trade in goods experienced the steepest decline ever recorded, with both exports and imports dropping four times more than income (Freund 2009, Levchenko et al. 2010). The fall was severe, highly synchronised across countries, and mostly concentrated in the category of durable goods (Baldwin 2009). Surprisingly, trade in services was relatively unaffected by the shock. Business, telecommunication and financial services, which constitute more than half of trade in services in modern economies, continued growing at their pre-crisis rates and only the category of transport services declined (Borchert and Mattoo 2009). In a new paper, I provide evidence on the reaction of both goods and services exporters to the 2008-2009 crisis and I analyse the reasons behind the peculiar resilience of services trade (Ariu 2016).

The Crisis

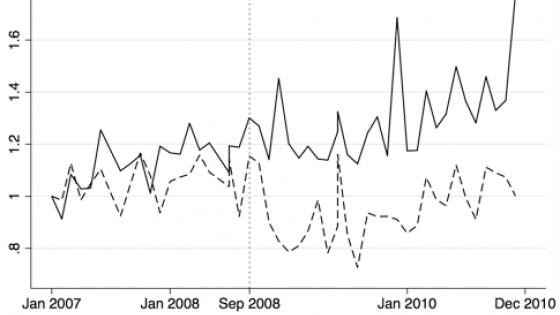

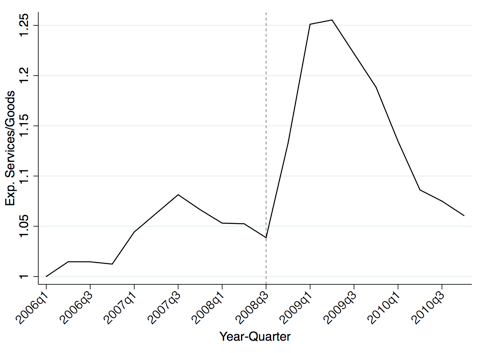

Figure 1 plots monthly exports for both trade in goods and trade in services using data on Belgian firms coming from the National Bank of Belgium. The dashed line shows that, in line with other countries, Belgian merchandise trade fell by about 30% after September 2008. The solid line however does not display any sign of discontinuity. Trade in services exhibits similar growth patterns before and after September 2008. Services continued growing more or less at the same pace regardless of the shock. This service resilience is not related only to Belgium. Figure 2 shows that the ratio of quarterly exports of services over exports of goods for the OECD increased substantially following the Lehman Brothers' collapse in the third quarter of 2008. This means that while trade in goods was declining, trade in services did not decline in most of the OECD countries. This pattern was particularly strong for Canada, Austria, France, and Japan while it is not clearly present only in very few countries.1

Figure 1. Belgian monthly exports, Jan 2007=1

Figure 2. Quarterly ratio of services/goods OECD exports, 2006Q1=1

Firms’ reaction

By decomposing Belgian exports’ flows, we observe that both goods and services exporters reacted similarly to the same shock. They kept the same number of destinations and products per destination and they adjusted the average value of their shipments (per product and destination). However, this qualitative similarity masks a huge quantitative difference. Firms exporting services decreased the average value of their transactions by only 4%, while those exporting goods did so by 27%. Therefore, firms did not destroy their international trade network, but they adjusted their shipments’ values. Services related to transport experienced a drop commensurate to that of goods. On the other hand, business, financial and telecommunication services (which represent more than 50% of Belgian services exports) continued their sustained growth. For goods exports, all product categories experienced a decline, yet the bulk of the collapse came from durable and capital goods and the decline was equally spread across all destinations.

Understanding the causes of the resilience

Both supply and demand factors could explain the special resilience of services.

Supply

- Banks reduced the availability of external capital for exporters, thus driving down aggregate trade volumes (Chor and Manova 2012, Ahn et al. 2011, Auboin 2009, Amiti and Weinstein 2011). To the extent that service exporters rely less on external trade capital,2 this can be a reason why services exports did not fall.

- The international nature of global value chains makes downstream demand shocks propagate through them with magnified upstream volatility due to inventory adjustments (Altomonte et al. 2012, Bems et al. 2011). Since services are intangible and thus not storable, they might have suffered less from the inventory adjustment process and from the disruption of global value chains.

- Service exporters might differ from goods exporters in various dimensions (size, productivity, multinational status, etc.) and that might have led to a different reaction of service trade to the same shock.

Demand

- Services might have a different and more resilient demand with respect to goods. For example, due to their intangibility they cannot be stored. This makes firms demand services continuously in order to keep the productive cycle active.3 If this is the case, their elasticity with respect to income shocks in destination countries should be different from that of goods.

Results

Using very detailed firm-product-destination export data for Belgium, I show that the cause of the different reactions is due to a different elasticity with respect to GDP growth in destination countries during the 2008-2009 crisis. In particular, the negative income shock in foreign markets affected exports of goods (especially exports of durable goods), but did not perturb the growth of services exports. This means that the main factor behind the trade in goods collapse (Behrens et al. 2011, Bricongne et al. 2012, Eaton et al. 2015, Levchenko et al. 2010) did not have any effect on trade in services. This different elasticity had important economic consequences. If goods exports had had the same elasticity to GDP growth as services, their fall during the 2008-2009 collapse would have been only half what was observed. The composition of exports and GDP helps understanding the different elasticity. Exports are predominantly composed of durable goods, which is the product category that dropped the most during the crisis (Behrens et al. 2011, Levchenko et al. 2010). Instead, GDP is mostly composed of services and consumable goods, which remained relatively stable during the crisis (Borchert and Mattoo 2009). Thus, exports of goods overreacted with respect to the negative GDP shock in destination countries, while exports of services did not.

When focusing instead on the role of supply factors, we find that credit constraints and firm heterogeneity did not affect services differently from goods. Therefore, besides playing a role in explaining the crisis, they are not responsible for the different behaviour.

Conclusion

This work shows that services tend to be more immune to short-term negative income shocks than goods exports. This is because their elasticity with respect to negative income variations tends to be lower than for goods. Therefore, services tend to suffer less when there is a sudden negative income shock. This suggests that services exports represent a viable solution for export growth also during adverse economic times.

References

Ahn, J., M. Amiti and D. E. Weinstein (2011), “Trade Finance and the Great Trade Collapse”, American Economic Review 101: 298–302.

Altomonte, C., F. D. Mauro, G. I. P. Ottaviano, A. Rungi and V. Vicard (2012), “Global Value Chains During the Great Trade Collapse: A Bullwhip Effect?”, CEP Discussion Papers No. 1131.

Amiti, M. and D. E. Weinstein (2011), “Exports and Financial Shocks”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1841–1877.

Ariu, A. (2016), “Crisis-Proof Services: Why Trade in Services Did Not Suffer During the 2008-2009 Collapse”, Journal of International Economics 98: 138-149.

Auboin, M. (2009), “Restoring Trade Finance: What the G20 Can Do”, in R. E. Baldwin and S. Evenett (eds), The Collapse of Global Trade, Murky Protectionism, and the Crisis. London: CEPR Press.

Baldwin, R. E. (2009), The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences and Prospects, London: CEPR Press.

Bems, R., R. C. Johnson and K.-M. Yi (2011), “Vertical Linkages and the Collapse of Global Trade”, American Economic Review 101: 308–12.

Borchert, I. and A. Mattoo (2009), “The Crisis-Resilience of Services Trade”, The Service Industries Journal 30(13): 2115–2136.

Behrens, K., G. Corcos and G. Mion (2011), “Trade Crisis? What Trade Crisis?”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 95: 702–209.

Bricongne, J.-C., L. Fontagné, G. Gaulier, D. Taglioni and V. Vicard (2012), “Firms and the Global Crisis: French Exports in the Turmoil”, Journal of International Economics 87: 134–146.

Chor, D. and K. Manova (2012), “Off the Cliff and Back? Credit Conditions and International Trade during the Global Financial Crisis”, Journal of International Economics 87: 117–133.

Eaton, J., S. Kortum, B. Neiman and J. Romalis (2015), “Trade and the Global Recession”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Francois, J. F. and J. Woerz (2009), “Follow the Bouncing Ball – Trade and the Great Recession Redux”, in R. E. Baldwin (ed.), The Great Trade Collapse: Causes, Consequences and Prospects, London: CEPR Press.

Freund, C. (2009), “The Trade Response to Global Downturns: Historical Evidence”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5015.

Levchenko, A. A., L. T. Lewis and L. L. Tesar (2010), “The Collapse of International Trade During the 2008-09 Crisis: In Search of the Smoking Gun”, IMF Economic Review 58: 214–253.

Endnotes

[1] Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Greece, and Iceland. See Ariu (2016) for country-level graphs.

[2] First, this can be related to the fact that many services can be traded over the internet, thus reducing the need for external finance to make the necessary investments to be able to export (Borchert and Mattoo 2009). Second, payments are faster for services. Production and consumption often coincide (this is especially true for modes 2, 3 and 4 defined in the GATS) and the risk of shipping delays is very low. As a result, the working capital needed to support the firm from production to delivery is lower. Moreover, this lack of payment delays lowers the need of export finance insurance. Third, service exporters might not be able to ask for external trade capital and may be used to work without it. This is because services are intangible and highly customised. Thus, they have little value outside the seller-buyer link and they can hardly be used as collateral.

[3] Services like call centre, maintenance or cleaning services must be constantly purchased in order to avoid any stop in the production.