A growing body of studies finds that cultural values and beliefs are important factors for social and economic development (Algan and Cahuc 2010, Collier 2017). However, our understanding of the interplay between culture and political institutions is still limited. While we have accumulated evidence about the effects that different institutional settings can have on the evolution of cultural traits (e.g. Tabellini 2010, Lowes et al. 2017, Becker et al. 2015), research on the effect of cultural traits on political or institutional outcomes is still in its infancy (Martinez-Bravo et al. 2017a, 2017b).

In a recent paper (Nunn et al. 2018), we seek to better understand how culture affects the political consequences of economic events. We examine the consequences of generalised trust, defined as the extent to which people believe that others can be trusted, for political stability in democratic and non-democratic regimes. Specifically, we posit that generalised trust affects how citizens evaluate their government’s performance in the face of severe economic downturns. In societies where trust is low, citizens may be less likely to trust the excuses of leaders and more likely to blame poor economic performance on poor decisions or low effort from politicians. In contrast, in societies where trust is high, citizens may be more likely to trust leaders when they argue that poor economic performance is outside of their control. This framework implies that, all else equal, economic recessions may be less likely to result in leader turnover in countries with higher levels of generalized trust, relative to countries with lower levels of trust.

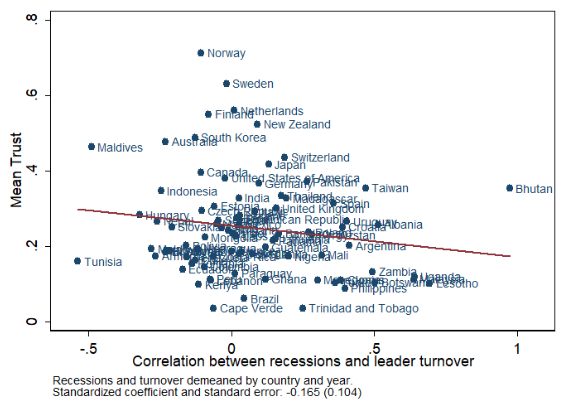

To illustrate the relationship between trust and political turnover during recessions for all countries for which data are available, we compute the correlation between recessions (defined as a period of negative average annual per capita GDP growth) and leader turnover for each country in the analysis, which is 0.070 (demeaning both variables by country and year). Figure 1 plots this country-level correlation against a country’s trust level. Since trust is a slow-moving cultural trait, we measure it as a time-invariant country-specific variable generated by averaging over all available surveys that ask the standard trust question.1

Figure 1 Bivariate correlation between countries’ level of generalized trust and the country-level correlation between the lagged occurrence of a recession and leader turnover

Although this correlation is informative, it is not conclusive. Omitted factors may exist that confound our interpretation of these relationships. Countries with different levels of trust may also differ in other ways that affect electoral turnover during recessions. For example, high trust countries may be richer on average, so policies that voters care about, such as public goods provision, may be less vulnerable to transitory economic downturns. At the same time, recessions may coincide with other events, such as military conflict, that can affect political turnover differentially across high- and low-trust countries. To address these difficulties, the analysis uses a difference-in-differences specification, with country and year fixed effects, and we control for a large number of possible omitted variables and conduct numerous placebo exercises to test the robustness of the main results.

We begin the analysis by focusing on democratic regimes, where citizens can more readily precipitate leader turnover through the mechanism of voting. The estimates show that when economic growth is negative, high-trust democracies are much less likely to experience leader turnover than low-trust countries. The magnitudes of the estimated effects are also sizeable. For example, according to the estimates, the presence of a recession is 12 percentage points more likely to cause political turnover in Italy than in Sweden. Similarly, it is 18.5 percentage points more likely to cause turnover in France than in Norway. The effects are large, especially given that mean turnover in the sample is 24.5%. The results are consistent with our hypothesis that in the face of a recession, individuals from low-trust countries are more likely to blame their politicians and remove them from office.

Since the electoral process plays an important role in this interpretation, we further examine the plausibility of our preferred mechanism by testing for the same effect among non-democracies. Consistent with our interpretation, we find no effect among non-democracies. We also find that the relationship only holds for regular leader turnovers, like those occurring due to elections, and not for irregular turnovers, like those occurring due to coups or assassinations.

As further confirmation of the importance of the electoral process for our main result, we test whether the effects that we find are most pronounced during election years. While we find effects in all years, the magnitude of the effect is much larger and more significant in election years. We also find that the effects are larger for parliamentary democracies than presidential ones, which may follow from the fact that parliamentary democracies have institutional procedures (i.e. a vote of no confidence) for removing the prime minister during the term. Moreover, we see the largest effects for democracies that have a fully free media and are more politically stable.2 Together, these results suggest that trust influences political turnover in the face of economic downturns by affecting the outcomes of elections.

The final issue that we consider is the question of how trust and leader turnover in the face of recessions affects economic recovery following the recessions. Specifically, is greater trust and the resulting leader stability helpful in aiding economic recovery? Examining our sample of democratic regimes, we find that countries with higher levels of trust experience faster economic growth in the years immediately following a recession. In addition, countries that do not experience leader turnover following a recession also have faster economic growth during this time. These estimates, although not causal, are consistent with higher trust resulting in less leader turnover following a recession, which, in turn, results in better economic recovery.

Our findings starkly illustrate the important interplay between culture, politics, and economics. They show how deeply rooted cultural traits, like trust, affect political outcomes, which in turn are important for economic performance. Moreover, the findings are also important for policymakers, since they provide some clues for forecasting political instability during economic downturns.

References

Algan, Y, and P Cahuc (2010), “Inherited trust and growth”, American Economic Review 100(5): 2060–2092.

Becker, SO, K Boeckh, C Hainz and L Woessmann (2016), “The empire is dead, long live the empire! Long-run persistence of trust and corruption in the bureaucracy”, Economic Journal 126(590): 40–74.

Collier, P (2017), “Culture, politics, and economic development”, Annual Review of Economics 20: 111–125.

Johnson, ND and AA Mislin (2011), “Trust games: A meta-analysis”, Journal of Economic Psychology 32(5): 865–889.

Lowes, S, N Nunn, JA Robinson and J Weigel (2017), “The evolution of culture and institutions: Evidence from the Kuba Kingdom”, Econometrica 85(4): 1065–1091.

Martinez-Bravo, M, G Padro-i-Miquel, N Qian, Y Xu, and Y Yao (2017a), “Making democracy work: Culture, social capital and elections in China”, Working Paper 21058, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Martinez-Bravo, M, G Padro-i-Miquel, N Qian, and Y Yao (2017b), “Social fragmentation, public goods and elections: Evidence from China”, Working Paper 18633, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Nunn, N, N Qian, and J Wen (2018), “Distrust and political turnover”, Working paper, Harvard University.

Tabellini, G (2010), “Culture and institutions: Economic development in the regions of Europe”, Journal of the European Economic Association 8(4): 677–716.

Endnotes

[1] “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” The reply “most people can be trusted” is coded as 1, while the reply “can’t be too careful” is coded as 0.

[2] We measure political stability in two ways: first, the average probability of leader turnover over the sample period, and second, the presence of a military conflict in the previous year.