Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, there has been an intense debate on the proper response to the current emergency, with many contributions focusing on the different aspects of the recovery (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020). In particular, the emergency is going to increase the need of public finance, making debt sustainability a much more serious concern, especially for emerging countries (which face a financial crisis as well as a public health emergency).

In a recent study, Horn et al. (2020), document the international response to a variety of disasters in the last 200 years. Based on new data collected by the authors over the last six years, they show that official (sovereign-to-sovereign) international lending is much larger than generally known. In particular, it spikes in times of global turmoil, such as wars, financial crises, or natural disasters, when private flows generally shrink (see Figure 1). Hence, it is reasonable to believe that official lending and debt is set to increase, even during this pandemic.

Figure 1 Official versus private capital flows, 1790–2015

Notes: The blue/red areas correspond to total official commitments. In comparison, the dashed black line shows the magnitude of global private cross-border capital flows as measured by Reinhart et al. (2016, 2020). All series are scaled by the main creditor’s GDP.

In recent weeks, 90 countries have approached the IMF for short-term emergency assistance, around twice the number that requested assistance in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Crisis (Krahnke 2020). During the Spring Meeting, the IMF has announced a set of measures aimed to help developing economies tackling both liquidity and solvency problems.1 In particular, for countries which are highly indebted and face solvency issues, the IMF (together with the World Bank) announced that they had already granted debt relief to 25 of the world's poorest countries by cancelling repayments owed to the fund over the next six months. The G20 has also agreed to a debt service ‘standstill’ on bilateral loans for a group of 76 low-income countries, even if private creditors were not asked to participate in the standstill (Bolton et al. 2020). More extreme measures will probably be necessary before the crisis is over, including a broader restructuring in concert with rich countries, especially if lookdowns last longer than anticipated.

As we expect a wave of debt restructuring in the following years (as a consequence of the COVID-19 emergency), it would be important to have some information about how sovereign agencies (and the bond market) evaluate this type of event. This is an issue that is of relevance but that has not received enough attention in research to date.

In two recent papers (Marchesi and Masi 2020a, 2020b), we study the relationship between sovereign debt (final) restructuring and sovereign ratings, by distinguishing between commercial and official debt, and by considering the creditors' loss (or ‘haircut’). We denote a restructuring deal with private creditors (foreign banks and bondholders) as ‘private restructuring’, while ‘official restructuring’ stands for agreements reached with official creditors (in the Paris Club of official creditors). We take institutional investor's indexes as measures of a given country's creditworthiness (Marchesi and Masi 2020a). Results are similar using agency rating and bond yield spread (Marchesi and Masi 2020b). The focus is on debt restructuring events, which take place at the end of a default or re-negotiation spell.

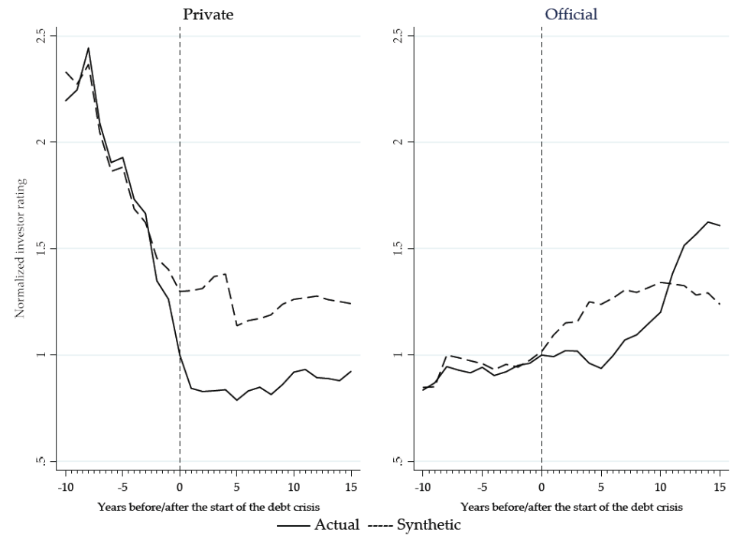

Consistent with Schlegl et al. (2019), the main result is that private credit events are more costly than official ones when it comes to ratings. Moreover, the rating decline is larger for cases with deeper haircuts. On the other hand, official defaulters are not affected (and may even benefit) by the final restructuring, which can take years after the default occurs. Using the synthetic control method, we find further evidence for the heterogeneity of the economic impact of debt restructurings (see Figure 2), confirming that official and private restructurings may have different costs, and then induce selective defaults.

Figure 2 Average effects on private and official defaulters

Notes: In each graph, the continuous line represents the average investor rating for the defaulting countries, while the dashed line shows the average outcome for the synthetic countries. Investor rating is normalized to 1 in period 0.

Even if these results depend on how institutional investor incorporates official risk into their rating models, they are important as they show that the costs of default vary with the amounts of debt and the type of creditors affected. Defaulting on private debt is highly visible and hence more likely to result in a rating downgrade, while an official default is generally much less visible and hence less likely to determine some negative spillovers. In particular, official restructurings that are arranged within the ‘Paris club umbrella’ are supposed to guarantee a relatively smoother approach to the way in which deals are actually orchestrated in comparison to the private case (further lowering the collateral damage of a default).

Concluding remarks

Sovereign debtors, aware that the consequences of a default may depend on who the defaulted creditors are, may decide to prioritise their repayments accordingly. Our results provide some further insight with regards to the debate on the consequences of debt heterogeneity, which introduces the possibility for governments to operate selective defaults discriminating across investors. Documenting this difference can then help to shed light on why countries default towards various lenders, and why they even default in the first place.

References

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro (2020), Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes, VoxEU.org eBook, London: CEPR Press.

Bénassy-Quéré, A, G Corsetti, A Fatás, G Felbermayr, M Fratzscher, C Fuest, F Giavazzi, R Marimon, P Martin, J Pisani-Ferry, L Reichlin, H Rey, M Schularick, J Südekum, P Teles, N Véron and B Weder di Mauro (2020), “COVID-19 economic crisis: Europe needs more than one instrument”, VoxEU.org, 05 April.

Bolton, P, L Buchheit, P O Gourinchas, M Gulati, C T Hsieh, U Panizza and B Weder di Mauro (2020), “Necessity is the mother of invention: How to implement a comprehensive debt standstill for COVID-19 in low- and middle-income countries”, VoxEU.org, 21 April.

Erce, A, A Garcia Pascual and R Marimon (2020), “The ESM can finance the COVID fight now”, VoxEU.org, 06 April. https://voxeu.org/article/esm-can-finance-covid-fight-now

Horn, S, C Reinhart and C Trebesch (2020), “Coping with disasters: Lessons from two centuries of international response”. VoxEU.org, 20 March.

Horn, S, J Meyer and C Trebesch (2020), “Coronabonds: The forgotten history of European Community debt”, VoxEU.org, 15 April.

Krahnke, T (2020), “Doing more with less: How the IMF should respond to an emerging markets crisis”, VoxEU.org, 14 April.

Marchesi, S and T Masi (2020a), “Sovereign Rating after Private and Official Restructuring”, Economic Letters 192: 1-7.

Marchesi, S and T Masi (2020b), “The Price of Haircuts: Private and official default", Centro Studi Luca d'Agliano Working Paper 460.

Reinhart, C M, V Reinhart and C Trebesch (2016), “Global Cycles: Capital Flows, Commodities, and Sovereign Defaults”, American Economic Review 106(5): 574–80.

Reinhart, C M, V Reinhart, and C Trebesch (2020), “Capital Flow Cycles: A Long, Global View”, Mimeo, forthcoming.

Schlegl, M, C Trebesch and M L J Wright (2019), “The Seniority Structure of Sovereign Debt”, NBER Working Paper 25793.

Endnotes

1 The proper European response to the coronavirus crisis is also very much debated, the ESM loans and Coronabonds seeming the most prominent alternatives (e.g. Bénassy-Quéré et al. 2020