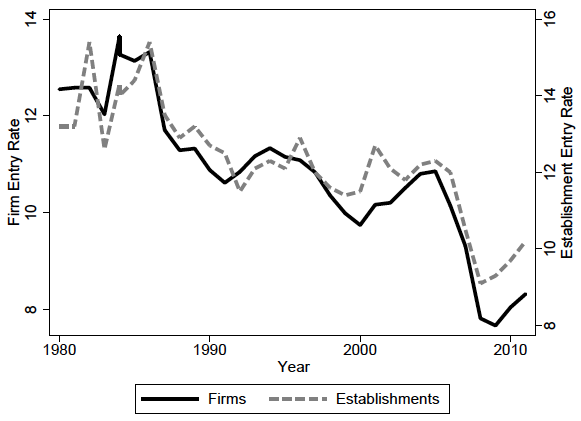

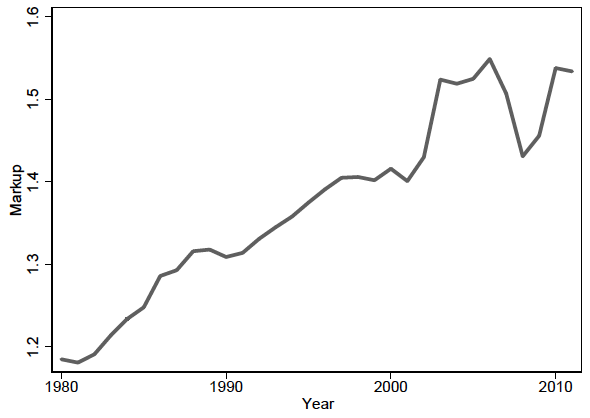

The US economy has been losing its business dynamism since the 1980s and especially since the 2000s. This shift has manifested itself in a number of empirical regularities – the entry rate of new businesses (Figure 1a), the job reallocation rate, and the labour share have all been decreasing (Decker et al. 2016, Karabarbounis and Neiman 2013, Barkai 2017, among others). Yet, the profit share, market concentration, and markups (Figure 1b) have all been rising (e.g. Autor et al. 2017a, 2017b, De Loecker and Eeckhout 2017, Gutiérrez and Philippon 2016, 2017, Eggertsson et al. 2018, Farhi and Gourio 2018). These trends have drawn notable attention from academic as well as policy circles. Indeed, the Federal Trade Commission has recently held “Hearings on Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century” with special attention given to competition and market concentration. While suggestions for the potential drivers of these structural shifts are abundant, there is little consensus in the literature on the underlying cause(s) that could jointly account for these potentially related developments.

Figure 1 Entry rates and markups

a) Firm and establishment entry rate

b) Average markups

Notes: Panel a is based on authors’ calculations from Business Dynamics Statistics database. Panel b is taken from De Loecker and Eeckhout (2017).

In two recent complementary papers, we contribute to this important, and predominantly empirical, debate by offering a new micro-founded macro model – which provides a unifying theoretical framework that can speak to all those symptoms – conducting a quantitative investigation of alternative mechanisms that could have led to these dynamics, and presenting some new facts on the rise of patenting concentration. In Akcigit and Ates (2019a), we review the findings of the literature and focus on the following prominent regularities:

- Market concentration has risen.

- Average markups have increased.

- The profit share of GDP has increased.

- The labour share of output has gone down.

- The rise in market concentration and the fall in labour share are positively associated.

- Productivity dispersion of firms has risen. Similarly, the labour productivity gap between frontier and laggard firms has widened.

- Firm entry rate has declined.

- The share of young firms in economic activity has declined.

- Job reallocation has slowed down.

- The dispersion of firm growth has decreased.

Our review of these trends and various changes in the economy that might have led to these trends directs our attention to a certain class of models. Accordingly, we build a theoretical model that accounts for, in particular, endogenous market power and strategic competition among incumbents and entrants, reflecting ‘best versus the rest’ dynamics. In Akcigit and Ates (2019b), we extend and calibrate this model to the US economy. Importantly, our quantitative analysis replicates the transitional dynamics of the US economy in the past three decades. Our decomposition exercises demonstrate decisively that distortions to the diffusion of knowledge across firms in the economy are the likely culprit behind declining US business dynamism.

Model description

Our theoretical framework centres on an economy that consists of many sectors. In each sector, two incumbent firms, which can also be interpreted as the best and the rest, compete à la Bertrand for market leadership. This competitive structure forces market leaders to post a limit price. Hence, the markups evolve endogenously as a function of the technology gap between firms. Market leaders try to innovate in order to open up the lead and increase their markups and profits. Follower firms try to innovate with the hope of eventually leapfrogging the market leader and gaining market power. In this race, knowledge diffusion, which occurs at an exogenous rate, allows followers to learn from the market leaders and quickly catch up with them. Likewise, new firms attempt to enter the economy with the hope of becoming a market leader someday.

A very important aspect of the model is firms’ strategic innovation investment. Intense competition among firms, especially when the competitors are in a neck-and-neck position in terms of their productivity levels, induces more aggressive innovation investment and more business dynamism. Yet when the leaders open up their technological lead, followers lose their hope of leapfrogging the leader and lower their innovation effort. Likewise, entrants get discouraged when markets are overwhelmingly dominated by the market leader, and so the entry rate decreases.

Our structural model allows us to analyse several important margins that shape the competition dynamics: corporate taxes, R&D subsidies, entry costs, knowledge diffusion, a decline in the interest rates, a fall in research productivity, and a decrease in workers’ market power relative to employers/firms.

Quantitative findings

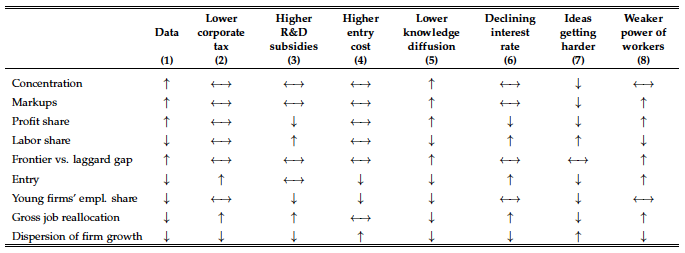

We calibrate the model to pre-1980 targets in the data – which include firm entry, aggregate markups and output growth – as if the US economy was in a steady state. Next, we focus on the transitional dynamics of the model economy and assess the ability of alternative channels mentioned earlier to generate observed trends in the model. We introduce shocks to each channel one at a time (in a way disciplined by the data) and compare the model-generated responses of each variable over the transition path. Table 1 compares the directions of model-based responses to changes in each mechanism with those of their empirical counterparts. The findings emphasise the differential ability of the knowledge diffusion channel for accounting for the observed trends. Another exercise, in which we decompose the contribution of alternative channels to the model-generated path of each variable, corroborates these findings.

Table 1 Qualitative experiment results for alternative mechanisms

Notes: Upward arrows indicate an increase in the variable of interest, downward arrows indicate a decline, and flat arrows indicate no or negligible change. If the absolute magnitude of the response of a variable is less than 20% of the actual change in the data, we denote it by a flat arrow.

When knowledge diffusion slows down over time, as a direct effect, market leaders are shielded from being copied, which helps them establish stronger market power. When market leaders have a bigger lead over their rivals, the followers get discouraged; hence, they slow down. The productivity gap between leaders and followers opens up. The first implication of this widening is that market composition shifts to more concentrated sectors. Second, limit pricing allows stronger leaders (leaders further ahead) to charge higher markups, which also increases the profit share and decreases the labour share of GDP. Since entrants are forward looking, they observe the strengthening of incumbents and get discouraged; therefore, entry goes down. Discouraged followers and entrants lower the competitive pressure on the market leader: When they face less threat, market leaders relax and they experiment less. Hence, overall dynamism and experimentation decrease in the economy.

Trends in the US patent data

Based on our findings, a natural follow-up question is: what caused a decline in knowledge diffusion? To elaborate on this question, we present new evidence on the use (or abuse) of patents in the US. Patent and reassignment data from the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) provide a fertile ground for investigating patterns of knowledge diffusion, as firms rely heavily on patent protection to shield themselves from imitators. A decline in imitators’ ability to copy and learn from market leaders’ technology due to heavier, and especially strategic, use of patents by the leaders would limit the flow of knowledge between firms and lead to a reduction in the intensity of knowledge diffusion. Therefore, we now turn our attention to the changes in the use of patents in the US economy across time.

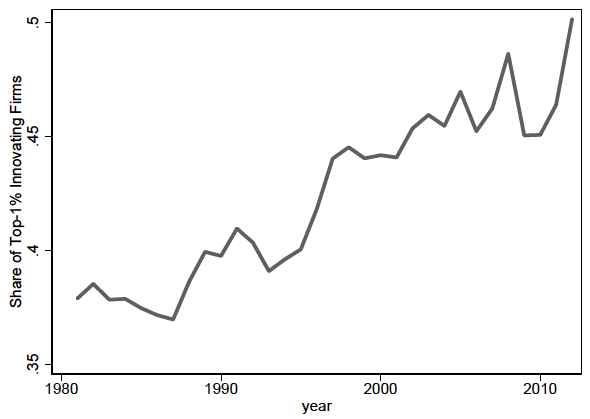

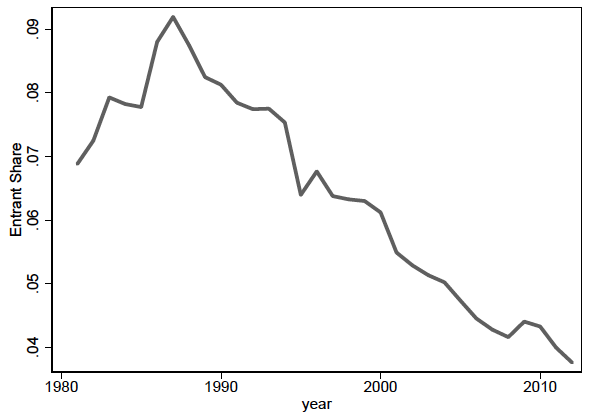

Figure 2a looks at the share of patents registered by the top 1% of innovating firms with the largest patent stocks. The ratio exhibits a dramatic increase. In addition, the share of patents registered by new entrants (firms that patent for the first time) exhibits the opposite trend, notwithstanding the small pickup in the early 1980s (Figure 2b).

Figure 2 Registry of patents

a) Share of patents in the top 1% of patenting firms

b) Entrants’ patent share over time

Notes: Based on authors’ calculations from USPTO data. Panel a shows the share of patent applications registered by top 1% of firms with the largest patent stocks in total applications made. Reciprocally, Panel b shows the share of applications registered by entrant firms, i.e., firms that patent for the first time.

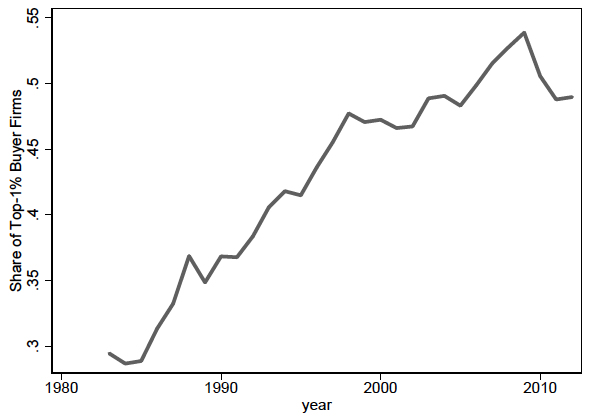

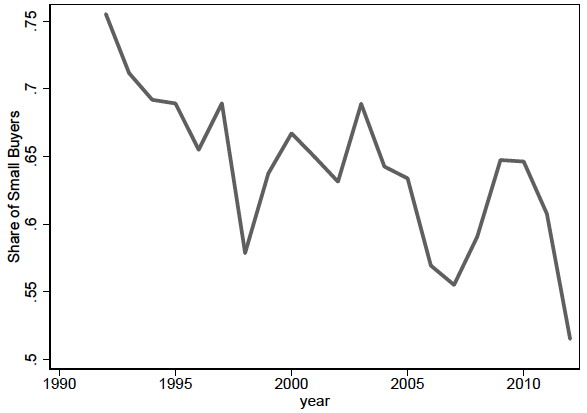

As in patent registries, we observe stark trends in patent reassignments since the 1980s. Figure 3a focuses on the purchasing trends of the top 1% of firms with the largest patent portfolios. The figure reveals that while 30% of the transacted patents were reassigned to the firms with the largest patent stocks in the 1980s, the share went up to 55% by 2010. This drastic increase has crowded out small players in the market, as illustrated in Figure 3b. The figure shows the likelihood of a patent to be assigned to a small firm, conditional on that patent being transacted from another small firm and recorded. In the past two decades, the fraction of transacted patents that are reassigned to small firms has dropped dramatically, implying a shift of ownership from the hands of small firms to large ones. These figures reveal that concentration in patent production and reassignment has surged, and firms with the largest patent (knowledge) stock have further expanded their intellectual property arsenals. Given that patents are exclusively used to prevent competitors from using the patent holders’ technology, these trends can imply that the heavy use of patents by market leaders might have caused the decline in knowledge diffusion from the best to the rest.

Figure 3 Reassignment of patents

a) Share of top 1% buyers over time

b) Share of small buyers over time

Notes: Based on authors’ calculations from US Patent and Trademark Office data. Panel a shows the share of patents reassigned to top 1% of firms with the largest patent stocks among all reassigned patents. Reciprocally, Panel b shows the share of applications registered to small buyers.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System.

References

Akcigit, U, and S T Ates (2019a), “Ten Facts on Declining Business Dynamism and Lessons from Endogenous Growth Theory,” NBER Working Paper 25755.

Akcigit, U, and S T Ates (2019b), “What Happened to U.S. Business Dynamism?,” NBER Working Paper 25756.

Autor, D, D Dorn, L F Katz, C Patterson, and J Van Reenen (2017a), “Concentrating on the Fall of the Labor Share,” American Economic Review 107(5): 180–85.

Autor, D, D Dorn, L F Katz, C Patterson, and J Van Reenen (2017b), “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms,” NBER Working Paper 23396.

Barkai, S (2017), “Declining Labor and Capital Shares,” University of Chicago, mimeo.

Decker, R A, J C Haltiwanger, R S Jarmin, and J Miranda (2016), “Declining Business Dynamism: What We Know and the Way Forward,” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 106(5): 203–07.

De Loecker, J, and J Eeckhout (2017), “The Rise of Market Power and The Macroeconomic Implications,” NBER Working Paper 23687.

Eggertsson, G B, J A Robbins, and E G Wold (2018), “Kaldor and Piketty’s Facts: The Rise of Monopoly Power in the United States,” NBER Working Paper 24287.

Farhi, E, and F Gourio (2018), “Accounting for Macro-Finance Trends: Market Power, Intangibles, and Risk Premia,” NBER Working Paper 25282.

Gutiérrez, G, and T Philippon (2016), “Investment-less Growth: An Empirical Investigation,” NBER Working Paper 22897.

Gutiérrez, G, and T Philippon (2017), “Declining Competition and Investment in the U.S.,” NBER Working Paper 23583.