Although the US economy has grown substantially over the last half century, there is no disputing that the benefits of this growth have been unevenly distributed. There is also solid evidence that some segments of the population are actually worse off than their counterparts of earlier generations. One recent study (Guvenen et al. 2017) finds that the median lifetime income of men born in the 1960s is 12–19% lower than that of men born in the 1940s. Another highlights that the share of medical expenses to consumption has approximately doubled every 25 years since the 1950s (Hall and Jones 2007). And Case and Deaton (2015, 2017) have started an important debate by showing that the mortality rate of white, less-educated, middle-aged men has been increasing since 1999.

While very suggestive, changes in lifetime income tell us little about what has happened to wages. And differences in how medical expenses and mortality have changed for married and single men and women can also influence the strength of their ultimate impact on couples, and on singles of both genders.

In recent research (Borella et al. 2019), we compare life outcomes of two cohorts born 20 years apart to explore these issues, and we find that, indeed, the American dream – the idea that regardless of background, every child can prosper as an adult – has undeniably vanished for the more recent generation of white, less-educated Americans.

Deterioration in lifetime opportunities

We compare wages, medical expenses, and life expectancy for white, non-college-educated single and married men and women born in the decade around 1940 with those of their counterparts born 20 years later – a cohort 49 to 58 years old as of 2014. We then analyse how those differences have affected these two cohorts’ labour market outcomes and how they will affect their lives in retirement. Our goal is to better measure these important changes in lifetime opportunities and uncover their effects on the labour supply, savings, and welfare of a relatively recent birth cohort using a structural model.

In brief, we find a profound deterioration in lifetime opportunities. Inflation-adjusted wages declined for non-college-educated white men. And while wages increased for women, it is only because their human capital (education and labour market experience) drastically increased over this time period. These men and women – who make up 60% of their age group – are also expected to face much higher out-of-pocket medical expenses in retirement and large decreases in life expectancy compared with their earlier counterparts. They would have been much better off if they had faced the corresponding lifetime opportunities of the 1940s birth cohort.

We focus on whites for methodological reasons – the need for a sufficiently large and homogeneous data set – not from a sense that they alone suffer bad times. White, non-college-educated Americans are hardly the only disadvantaged population losing ground. A substantial body of research (Neal 2011, Neal and Rick 2016, Bayer and Charles 2018) has confirmed stagnant wages and dramatic declines in employment rates for less-skilled black men, along with rising incarceration rates and persistent black-white skill gaps.

Generational change, for the worse

To arrive at these conclusions, we construct a sample of white, non-college-educated Americans from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and Health and Retirement Study (HRS), picking a cohort born in the 1940s because it is the oldest cohort with solid data for an entire life cycle. The data cover people who are white, have less than 16 years of education, and were born between 1936 and 1945. A comparison is made with the cohort of whites with the same educational achievements but born 20 years later, between 1956 and 1965.

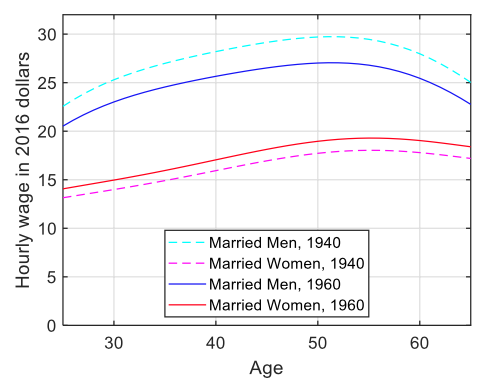

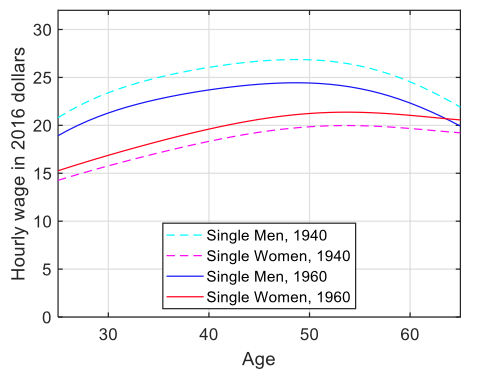

We find that men’s average wages dropped by 9% (inflation adjusted). Women’s wages were 7% higher, but again, only because of higher human capital (Figure 1). Out-of-pocket medical expenses after age 66 increase by 82% (Figure 2). Life expectancy at middle age declines by 1.7 years for men and 1.1 years for women (Table 1). All of these changes are thus large, with the potential to substantially affect behaviour and welfare.

Figure 1 Potential wage profiles, comparing 1960s and 1940s for married people (top panel) and single people (bottom panel)

Figure 2 Average out-of-pocket medical expenses for cohorts born in the 1940s and 1960s

Table 1 Life expectancy for white, non-college-educated men and women born in the 1940s and 1960s cohorts

Source: HRS data

Impact of change on behaviour

To understand the impact of such changes on lifetime outcomes, we use a life-cycle model of labour supply and savings with single and married people who face possible change in marital status, which incorporates skill building on the job and includes medical spending and longevity risk. We gauge the impact that the later generation’s worse wage schedules, medical expenses, and life expectancy profiles have had on their labour supply, savings, and welfare by replacing values for each of these factors by that of the older generation. We first analyse one input at a time – wages, health costs, life spans – and then all three together.

The effects of these changes on labour supply and savings vary by demographic group (male, female, single, married), but in most cases, the impact is substantial. If wages had stayed at 1940s schedules, for example, while health expenses and life spans had changed to 1960s levels, married couples born in the 1960s would have had the most different labour market outcomes – husbands would have stayed in the labour force much longer, and wives would have had lower participation rates and working fewer hours because of the much higher wages for men in the 1940s.

Changing health expenses or life spans alone would have altered labour outcomes less significantly. The decrease in life expectancy mainly reduced retirement savings, but the expected increase in out-of-pocket medical expenses increased them even more.

Substantial welfare losses

The final question is the impact on overall welfare. We estimate the lump-sum compensation that a 25-year-old individual born in the 1960s would require to be indifferent between the 1940s and 1960s wages, medical expenses, and health and survival dynamics. The sums are large – $126,000 for single men, $44,000 for single women and for couples. Lower wages account for most of the welfare loss – between 47% and 58% depending on demographic group. Shorter life expectancies explain 26% to 34% of the decrease in well-being, and higher medical expenses account for the rest.

These deep welfare losses, along with the associated effects on labour supply, health care spending, and asset accumulation, contrast starkly with the US economy’s strong aggregate growth, indicating that this large segment of the population has not enjoyed the fruits of that broad economic health. By illuminating that difference, this research can serve well in any effort to evaluate to what extent current government policies attenuate these kinds of shocks and whether policies should be redesigned to reduce their impact.

References

Bayer, P, and K K Charles (2018), “Divergent Paths: A New Perspective on Earnings Differences Between Black and White Men Since 1940”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133 (3), 1459–1501.

Borella, M, M De Nardi, and F Yang (2019), “The Lost Ones: The Opportunities and Outcomes of White, Non-College Educated Americans Born in the 1960s”, NBER Working Paper no. 25661.

Case, A, and A Deaton (2015), “Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (49), 15078–15083.

Case, A, and A Deaton (2017), “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring).

Guvenen, F, G Kaplan, J Song, and J Weidner (2017), “Lifetime Incomes in the United States over Six Decades”, NBER Working Paper no. 23371.

Hall, R E, and C I Jones (2007) “The Value of Life and the Rise in Health Spending”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122 (1), 39–72.

Neal, D (2011), “Why Has Black-White Skill Convergence Stopped?” In E A Hanushek and F Welch (eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 1, 511–576, Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Neal, D, and A Rick (2016), “The Prison Boom and Sentencing Policy”, Journal of Legal Studies, 45 (1), 1–41.