While the world’s population is on an increasing path for the decades to come, the industrial world is confronted with aging populations and, in an increasing number of countries, shrinking population size. According to the most recent UN projections (see Table) the populations of 45 countries are expected to shrink between now and the year 2050. Among them are countries like Japan, Germany, Italy and most countries in Middle and Eastern Europe.

Country population prospects

|

|

Population (thousands) |

|

Difference |

|

|

|

2007 |

2050

|

Absolute

|

Percentage

|

|

Bulgaria

|

7,639

|

4,949

|

-2,690

|

-35.2

|

|

Ukraine

|

46,205

|

30,937

|

-15,268

|

-33.0

|

|

Belarus

|

9,689

|

6,960

|

-2,729

|

-28.2

|

|

Romania

|

21,438

|

15,928

|

-5,509

|

-25.7

|

|

Russian Federation

|

142,499

|

107,832

|

-34,667

|

-24.3

|

|

Moldova

|

3,794

|

2,883

|

-910

|

-24.0

|

|

Latvia

|

2,277

|

1,768

|

-509

|

-22.4

|

|

Lithuania

|

3,390

|

2,654

|

-736

|

-21.7

|

|

Poland

|

38,082

|

30,260

|

-7,822

|

-20.5

|

|

Japan

|

127,967

|

102,511

|

-25,455

|

-19.9

|

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina

|

3,935

|

3,160

|

-775

|

-19.7

|

|

Croatia

|

4,555

|

3,692

|

-864

|

-19.0

|

|

Hungary

|

10,030

|

8,459

|

-1,570

|

-15.7

|

|

Estonia

|

1,335

|

1,128

|

-207

|

-15.5

|

|

Slovenia

|

2,002

|

1,694

|

-308

|

-15.4

|

|

TFYR Macedonia

|

2,038

|

1,746

|

-293

|

-14.4

|

|

Slovakia

|

5,390

|

4,664

|

-726

|

-13.5

|

|

Czech Republic

|

10,186

|

8,825

|

-1,361

|

-13.4

|

|

Germany

|

82,599

|

74,088

|

-8,512

|

-10.3

|

|

Italy

|

58,877

|

54,610

|

-4,267

|

-7.2

|

|

Portugal

|

10,623

|

9,982

|

-641

|

-6.0

|

|

Channel Islands

|

149

|

144

|

-5

|

-3.5

|

|

Greece

|

11,147

|

10,808

|

-339

|

-3.0

|

|

Serbia

|

9,858

|

9,635

|

-224

|

-2.3

|

Source: United Nations (2007)

Though even at the national level the population loss is often quite substantial (up to one third until the year 2050), population trends in disadvantaged regions are in some cases expected to be even more dramatic. As a consequence, even countries with a stable or mildly declining overall population will face the consequences of dramatic population shrinking on the regional level. The following table clarifies this by presenting Eurostat population projections up to the year 2030. It is clear that certain European regions face a dramatic decline of their population with up to almost 30%, even when regarding this shorter time period (i.e., 2030 rather than 2050, as before).

Regional population prospects for selected Western European regions

|

Country

|

Region

|

Projected population change 2007-2030 (in %)

|

|

Germany

|

Dessau

|

-29

|

|

Germany

|

Magdeburg

|

-20

|

|

Greece

|

Voreio Aigaio

|

-19

|

|

Germany

|

Dresden

|

-16

|

|

Spain

|

Principado de Asturias

|

-14

|

|

Italy

|

Liguria

|

-12

|

|

Germany

|

Leipzig

|

-11

|

|

Spain

|

Castilla y León

|

-10

|

|

Spain

|

Galicia

|

-10

|

|

Italy

|

Basilicata

|

-10

|

|

Netherlands

|

Limburg

|

-10

|

|

Greece

|

Anatoliki Makedonia, Thraki

|

-9

|

|

Spain

|

País Vasco

|

-9

|

Source: Eurostat

Demographic change has so far attracted considerable academic attention with respect to the following fields:

- Growth economics: Recent research (An and Jeon, 2006) suggests an inverted U-shape relation between demographic change and economic growth. While initially the "demographic dividend" related to an increasing population share in working age pushes growth, the increasing share of the old and very old with progressing aging will be a growth burden.

- Social security: The negative impact of aging on the stability of health systems and pay-as-you-go pension systems is by now generally acknowledged. Substantial reform activity is already under way in the industrial world to stabilise pension systems by a combination of effective pension cuts, increasing the retirement age or the introduction of funded pillars (e.g., in Germany and Belgium to name but two cases).

- Public budgets: Public spending on many fields is highly age-dependent: e.g., child care, education policy or care for the elderly (Seitz and Kempkes, 2007). However, given the historic population developments in most Western countries (i.e., baby boom after WW-II and dramatic decline in birth rates afterwards), the expenditure-stimulating effects of population aging (e.g., old age care) are generally estimated to outweigh savings (e.g., in childcare or education).

In contrast to these insights, the impact of population shrinking – rather than ‘just’ aging – on the costs of public service provision has so far largely been neglected.

Scale economies and the public service vortex

The essential problem is the following: The production of many public services entails substantial fixed costs. A minimum staff size is often necessary to cover provision of all public services required by constitutional rules. For example, providing streets or wastewater networks involves significant set-up costs, which are to a considerable extent independent of the number of users. A shrinking population can then throw certain regions (be these countries, provinces or municipalities) into a downward spiral. Increasing cost pressures lead either to a deterioration of services or to increasing fees and local taxes. This impairs the region’s position in the competition for mobile workers and companies. A process of negative cumulative causation is the outcome, thereby further aggravating regional disparities.

While this theoretical reasoning is clear-cut, empirical work is necessary to identify the problem's relevance. New research by Geys et al. (2007) sheds first light on this issue using data on more than 1000 municipalities in the state of Baden-Württenberg (Germany). In this work, population scale elasticities in the German municipalities’ cost functions are studied in detail. The size of these population scale elasticities is essential for the consequences of demographic change since a low elasticity of costs to population changes signals a high probability for a vicious cycle of population losses, cost pressure and further outward migration. Technically, the analysis assesses the determinants of the cost of public good provision (e.g., the number of students in local public schools, the number of kindergarten places, the surface of public recreational facilities, the population over age 65, and the number of employees paying social security contributions), with a special focus on population size effects. Since German municipalities are characterised by a highly similar list of tasks, the focus on one particular country avoids the problem of institutional differences across countries. Moreover, the empirics account for differences in the environment of public good production such as population density or the unemployment rate. Hence, the cost function estimated on the basis of this modeling approach allows identifying scale elasticities in a profound way.

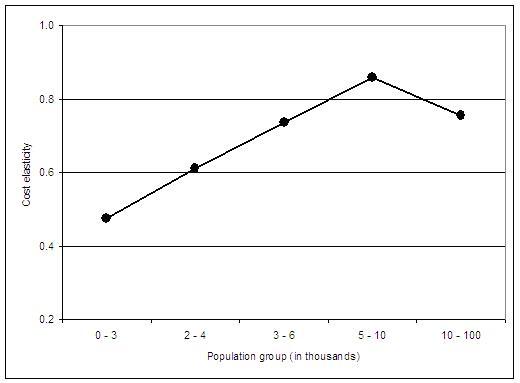

Development of cost elasticities with increasing size of population

The figure above summarises the key result: i.e., fixed costs are indeed a problem but only for certain size classes. For municipalities up to a size of 6000 inhabitants, the costs for providing public goods fall underproportionally with population size. That is, they are characterised by population-cost elasticities significantly below one. As such, a significant strain on local public budgets is to be expected for these entities with population decline. In contrast, larger municipalities are less confronted with the fixed cost problems and should, therefore, be more able to cut costs in proportion with falling population.

Of course, more research is needed to improve our understanding for the impact of population losses on public service production. If the above-mentioned results prove to be robust, demographic change in Europe could bring a further push for the growth of cities and agglomerations (at the detriment of rural areas). Hence, demographic change can be expected to have a substantial impact on the spatial distribution of economic activity in Europe. Already today the agglomerations are the growth leaders and migration magnets all over Western and Eastern Europe (European Commission, 2007). When municipalities in the rural areas find themselves in the population shrinkage-cost trap in the future, this tendency will accelerate. In this sense, cities and agglomerations are likely to be the ‘winners’ of demographic change.

References

An, Chong-Bum and Seung-Hoon Jeon (2006), 'Demographic change and economic growth: An inverted-U shape relationship'.

European Commission (2007), 'Growing Regions, Growing Europe', Fourth report on economic and social cohesion, Brussels.

Geys, Benny, Heinemann, Friedrich and Alexander Kalb (2007), 'Local Governments in the Wake of Demographic Change: Efficiency and Economies of Scale in German Municipalities', ZEW Discussion Paper No. 07-036, Manneim.

Seitz, Helmut and Gerhard Kempkes (2007), 'Fiscal Federalism and Demograpy', Public Finance Review, 35 (3), 385-413.

United Nations (2007), World Population Prospects, The 2006 Revision