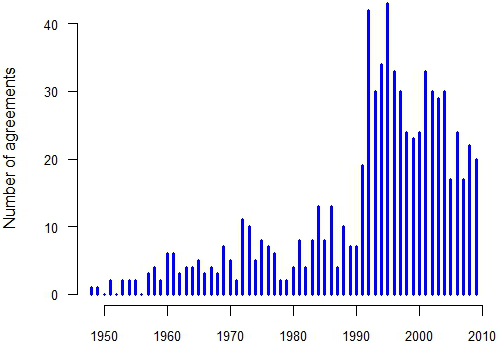

Preferential trade agreements (PTAs) have been around for quite some time, but only in about 1990 did they begin to proliferate rapidly. The world is only waiting for Mongolia to sign a PTA to be able to talk about them as a universal phenomenon, with the exception of some tiny islands (see Figure 1). While up to the 1990s, multilateralism was the most promising avenue for liberalising trade, today new PTAs, such as the US–EU trade agreement (known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership) are setting the benchmark for liberalisation, and exhibit innovation in terms of regulation.

Figure 1. Number of agreements signed

As a reaction to these new political and economic realities, research on PTAs has boomed in recent years (Mansfield and Milner 2012). Many arguments about the drivers have been put forward, including that the new generation of PTAs is strongly affected by the “trade-investment-service nexus” (Baldwin 2011, WTO 2011), and that diffusion is driving this process (Baccini and Dür 2012). What has been lacking is more fine-grained information on the depth, scope, and flexibility of PTAs.

The usefulness of new data

A new database ‘in the making’ attempts to shed more light on the design of PTAs in market access and trade-related areas (Dür et al. 2014). The database is substantially larger and more detailed than any of the existing databases and provides information on some 590 treaties (www.designoftradeagreements.org). These data may be of use in addressing many longstanding empirical puzzles, such as what type of agreement increases trade flows, what is the relationship between depth and flexibility, or what type of commitments travel across time and regions.

The DESTA database builds on more than 120 observations per treaty and allows researchers to construct measurable indicators for the degree of market opening, the scope of areas covered, the instruments to protect against 'unfair' competition, or legal provisions to enforce the rules.

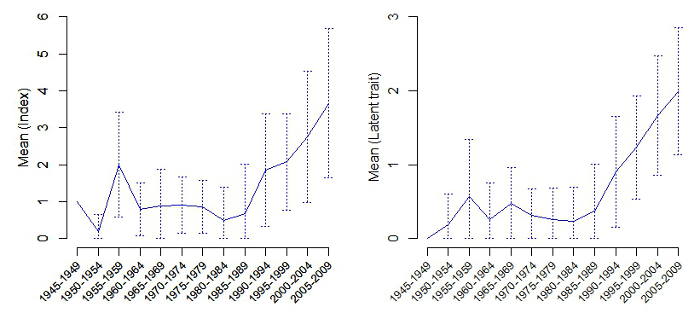

Figure 2 provides information on one such indicator, which we call depth. This reflects the degree to which a PTA promises to liberalise markets. As measuring the depth of agreements is tricky, we rely on two different approaches to operationalise this variable.

- The first is to calculate a simple, additive index that captures whether an agreement is a full free trade agreement, and whether it includes substantive provisions in areas that go beyond tariff reductions – services trade, investments, standards, public procurement, competition and intellectual property rights. This measure potentially ranges from 0 to 7.

- The second approach is to use latent trait analysis on 48 items that we coded to arrive at a measure of depth. As Figure 1 shows, since the early 1990s, agreements have become increasingly deep. Nevertheless, at any point in time, variation across agreements in terms of depth is wide.

Figure 2. Depth over time

Do design differences matter?

To respond to this question, we explored the effect of depth on trade flows. The take-home messages of our econometric analysis, which relied on a battery of different specifications of the gravity model, are three-fold.

- First, the level of promised liberalisation (depth) has a positive and statistically significant effect on trade flows. This finding is highly robust and the magnitude of the effect is large and outperforms the impact of the GATT/WTO on trade flows in every model specification.

- Second, deep PTAs, such as the EU and NAFTA, increase trade (at least) three times more than shallow PTAs, such as ASEAN or ECOWAS.

- Third, the effect of deep PTAs on trade is larger than the effect of shallow PTAs in the short-, medium-, and long-term. For instance, in our best model specification after 15 years, deep PTAs would increase trade by 45% [36, 54], while shallow PTAs would increase trade by 13% [7, 20].

In sum, there is strong evidence that the design of PTAs matters for increasing trade flows between member countries. Disregarding the considerable heterogeneity among PTAs leads to biased estimates of their effect on trade.

Concluding remarks

Future research should analyse the trade flow effects of PTAs differentiated by types of commitments (e.g. goods, services, and regulatory convergence) or characteristics of goods (producer versus consumer products). Moreover, the trade effects may be disaggregated at the sector level. Beyond its effect on trade flows, the depth of agreements may also have a bearing on political and institutional change in member countries. There is a large literature on how international institutions affect domestic policies to which DESTA could contribute. These are all areas to be further explored, and we hope our data can assist in tackling existing and new puzzles of international economic cooperation.

References

Baccini, Leonardo, and Andreas Dür (2012), “The New Regionalism and Policy Interdependence”, British Journal of Political Science 42(1): 57–79.

Baldwin, Richard (2011), “21st Century Regionalism: Filling the Gap Between 21st Century Trade and 20th Century Trade Rules”, WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2011-08.

Dür, Andreas, Leonardo Baccini, and Manfred Elsig (2014), “The Design of International Trade Agreements: Introducing a New Database”, Review of International Organizations, forthcoming.

Mansfield, Edward, and Helen Milner (2012), Votes, Vetoes, and the Political Economy ofInternational Trade Agreements, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

World Trade Organization (2011), World Trade Report 2011: Preferential Trade Agreements and the WTO: From Co-Existence to Coherence, Geneva: WTO.