The average annual net tax gap for 2008–2010 for the US, considered a relatively compliant country, is estimated to be $406 billion, or about 16.3% of what should be paid (IRS 2018). The net tax gap is the difference between required and actual timely filing, reporting, and payment of taxes after taking into account enforcement activities and late payments. Given the revenue at stake, substantial resources are invested in understanding how to improve tax compliance.

Fighting tax evasion is important because it reduces the government’s cost of raising revenue and because it makes the distribution of the tax burden fairer (Slemrod 2006). If revenue is raised more efficiently, it becomes possible to provide more public goods or to cut tax rates, keeping government debt constant.

Thanks to the wider availability of administrative data, and the increasing willingness and ability of administrative agencies to partner with academic researchers, academic research on how to reduce tax evasion is flourishing. Policies that reduce evasion include audits (Slemrod et al. 2001), third-party reporting (Kleven et al. 2011), paper trails (Pomeranz 2015), public disclosure of tax records (Bø et al. 2015), and satellite detection of unregistered buildings (Casaburi and Troiano 2015).

Enforcing employer tax compliance

Among the biggest flows of revenue into public coffers are the deposits employers make of payroll, excise, and withheld income tax; but there is not much evidence about the extent to which employers fail to make these deposits and why. In a recent paper – the product of cooperation between tax researchers at the University of Michigan and at the IRS – we analysed results from a field experiment in which the IRS randomly assigned 12,172 firms to either receive an in-person visit, a letter, or no treatment, comparing the tax deposits made by each group of randomly assigned firms and their network neighbours (Boning et al. 2018).

Most US employers are required to make regular tax deposits. Each quarter, an IRS algorithm identifies and prioritises firms who appear to be at high risk of falling behind on their required deposits. This experiment focused on a group of at-risk firms.

It is especially important to understand the behaviour of at-risk firms because they are the ones on the margin of IRS enforcement action – they are exactly the firms that the IRS has in mind when setting enforcement policy.

These firms were randomly assigned to one of three groups. A control group wasn’t contacted about their deposits. A second group received a letter noting that the firm’s deposits have decreased, discussing the firm’s deposit responsibility and potential penalties, and providing information and resources about federal tax deposits and their payment. The third group received an in-person visit at their place of business from an IRS Revenue Officer, who had the responsibility of providing the firm with information about the collection process, discussing the firm’s deposit compliance status and, in certain cases, determining that further investigation would be needed.

Randomisation ensures that the firms’ behaviour would have been similar on average if they had received the same treatment, so that any differences in the deposits remitted between the treatment and control groups were credibly caused by the letter or visit that the treatment groups received.

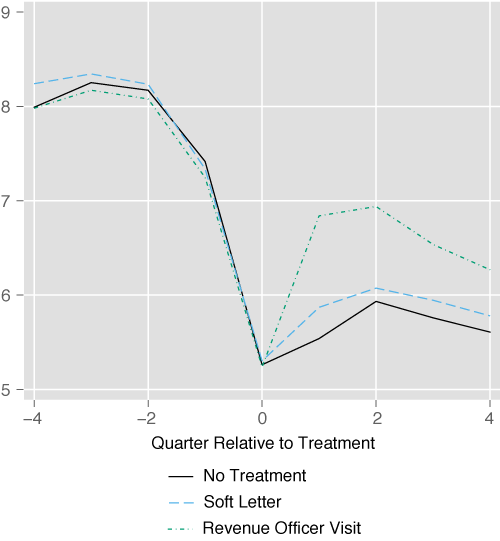

The direct effect of the Revenue Officer visit was a 276% increase in tax remitted by visited taxpayers relative to the control group one quarter after treatment, an effect that remained substantial one year after treatment. Receiving a letter increased remittances by 34% for a single quarter.

Figure 1 Log tax remitted on average by treatment and control groups before and after treatment

Network effects of tax enforcement

In addition to studying the effects on the firms that received a visit or letter, we also considered the ripple effects through their networks of connections via tax preparers and subsidiaries. Tax preparers and subsidiaries may be important channels through which firms pass on information about IRS enforcement they infer when they are treated.

While receiving the letter did not have significant network effects, receiving a Revenue Officer visit did, increasing tax remitted by 2% in the following quarter among the 24 firms, on average, sharing a tax preparer with each visited firm. In contrast, subsidiaries of visited firms reduced their tax remittances by 9.3%, a network effect that may reflect reallocation of resources within the enterprise rather than information diffusion.

On average, we found the IRS would collect an additional $111,324 when it visited a firm and $13,196 when it sent a letter to collect on withheld income and payroll tax deposits.

Setting tax administration budgets and priorities

These results are a reminder that, when adding up the costs and benefits of tax enforcement, it is important to take into account effects beyond the behaviour of the taxpayers who directly receive the intervention. The spillovers we find through tax preparers and subsidiaries are examples of the indirect effects enforcement may have, as are the effects through value-added-tax chains that Pomeranz (2015) finds.

Given a fixed tax authority budget, some approaches yield a higher return on investment than others. In the final part of the paper, we consider the cost effectiveness of the interventions. We find that both interventions (letter and in-person visit) are cost-effective ways to increase tax compliance. When setting tax authority budgets, both the direct and spillover effects of tax enforcement should be considered.

References

Bø, E E, J Slemrod, and T O Thoresen (2015), “Taxes on the Internet: Deterrence effects of public disclosure”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7(1): 36–62.

Boning W, J Guyton, R Hodge, J Slemrod and U Troiano (2018), “Heard it through the grapevine: Direct and network effects of a tax enforcement field experiment”, NBER Working Paper 24305.

Casaburi, L and U Troiano (2016), “Ghost-house busters: The electoral response to a large anti tax evasion program”, Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Kleven, H J, M B Knudsen, T Kreiner, S Pedersen, and E Saez (2011), “Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a randomized tax audit experiment in Denmark”, Econometrica 79(3): 651–692.

IRS (2018), "Tax Gap Estimates for Tax Years 2008-2010", 15 March.

Pomeranz, D (2015), “No taxation without information: Deterrence and self-enforcement in the Value Added Tax”, American Economic Review.

Slemrod, J, M Blumenthal, and C Christian (2001), “Taxpayer response to an increased probability of audit: Evidence from a controlled experiment in Minnesota”, Journal of Public Economics 79(3): 455–483.

Slemrod, J (2016), “Tax compliance and enforcement: New research and its policy implications”, University of Michigan, Working Paper.