It is well established that the distance between two countries substantially impacts the level of their economic relations. This gravity result is observed not only for trade (Anderson and van Wincoop 2003, Leamer 2007), but also for financial linkages (Aviat and Coeurdacier 2007, Brüggemann et al. 2011, Portes et al. 2011).

Does the relevance of gravity extend to fluctuations in international linkages during recessions and crises? In a new paper, we show that it does, and in a broad sense (Mehl et al. 2020). Understanding what drives the level of international linkages is important, as is understanding what drives their volatility. The transmission of external economic shocks through trade and financial channels is a central issue facing policy makers.

We show that international linkages are more volatile among countries with more distance between them, considering trade in goods and services, foreign direct investment, cross-border portfolio investment positions, and international banking linkages. In addition to geographical distance, we also consider measures of virtual distance based on internet linkages (Chung 2011, Hellmanzik and Schmitz 2016) and language distance (Melitz and Toubal 2019) that proxy for ease of communication. We document the role of distance during episodes of large contraction in trade, namely the 2008-2009 Global Crisis and the current Covid-19 pandemic, as well as more broadly through a panel analysis of trade over longer horizons.

The ‘beachhead’ and ‘footloose’ effects in theory

The impact of distance on the level of trade is relatively straightforward to establish in theory: iceberg trading costs are higher for more distant country pairs, leading to smaller trade in equilibrium. But this does not translate into a distance effect in terms of trade dynamics. As long as iceberg costs remain constant, trade flows move in step with final demand regardless of the level of costs. Of course, if we consider shifts to trading costs, these have a higher impact for more distant shipments (Berman et al. 2012).

A priori, the effect that distance has on the sensitivity of trade linkages to shocks is ambiguous. Exporters may be more willing to cut back further on marginal destinations, and focus on their core markets (a ‘footloose’ effect). But the opposite can hold true if exporters had to invest significantly to establish a presence in distant markets and are not willing to forego this investment (a ‘beachhead’ effect, in the spirit of Baldwin 1988). We develop a simple model based on Atkeson and Burstein (2008), with a nested constant elasticity of substitution (CES) structure wherein several firms from one country export to a destination market and compete with other firms there. As the elasticity of substitution is higher between two exporting firms than between exporting and local firms, an exporter with a high market share faces a lower effective elasticity of demand than an exporter with a low market share.

Firms face two types of fixed costs, and make two decisions. First, they decide whether to enter the export market based on expected demand, and pay an entry cost. Then they observe the level of demand, and decide whether or not to produce, paying an additional fixed cost to do so. The equilibrium level of firms is determined by a zero-profit condition. Distance is reflected in the fixed costs, which are higher for more distant country pairs.

This simple model shows that the impact of distance on the sensitivity of trade to shocks in final demand can go either way. If the fixed cost of production is dominant, we have a ‘footloose’ effect in which trade is more volatile for distant pairs. Intuitively, a reduction in final demand lowers profits and leads some exporters to exit. This raises the market share of the survivors, and lowers their effective elasticity of demand. The change in elasticity is moderate if there were many exporters initially, as they still mostly compete against one another after the shock. The change gains added importance if the number of exporters was initially limited, as they now compete more against domestic firms. The lower elasticity of demand boosts mark-ups, which amplifies the reduction in trade. A given drop in demand then has a larger impact on trade for more distant pairs where the number of exporters is limited.

If the fixed cost of entry is dominant, however, we have an opposite ‘beachhead’ effect, in which trade is more stable for distant pairs. Intuitively, many exporters enter a nearby market with a low entry cost. Once the entry cost is covered, the exporters achieve moderate profit margins. A moderate drop in demand is sufficient to push some exporters out, thereby leading to rising market shares for the survivors and a rise in mark-ups that amplifies the contraction. By contrast, such a drop in demand does not prompt an exit for distant country pairs, as the few exporters had to pay a sizable entry cost and have higher ex-post profitability buffers.

Our simple model shows two results. First, the sensitivity of trade to final demand depends on distance through the number of firms. Second, the relation can go in different directions depending on the specific structure of costs.

Evidence from the global crisis

We assess the role of distance by regressing the log change of international trade or financial linkages between 2007 and 2009 on geographical distance, virtual distance (Chung 2011), language distance (Melitz and Toubal 2014), and the usual range of gravity controls.

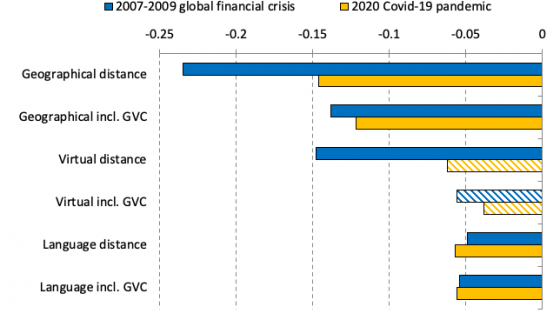

Figure 1 presents the estimated coefficients and shows that distance matters in a broad sense. Trade and financial linkages fell proportionately more in country pairs that are geographically further apart (in line with the findings of Galstyan and Lane 2013) for portfolio investment positions. But virtual distance also magnified the contraction, except for foreign direct investment (FDI) and banking linkages, possibly reflecting the fact that banks and multinational firms tend to have a local presence that reduces the need to rely on cross-country communication. Language distance also amplified the decline in trade and financial linkages.

Figure 1 Estimated effect of distance measures during the Global Crisis of 2007-09

Note: the figure shows the estimated coefficients from regressing the log change of the specific international linkage on the various measures of distance, controlling for the pre-crisis levels of the transactions in question, gravity controls, and source- and destination-country fixed-effects. The measures of distances are standardized to ease comparison across coefficients, so the coefficients show the percentage impact of a one-standard deviation increase in distance. The solid and striped bars show significant and non-significant coefficients, respectively.

The economic magnitude of the effects is substantial. Increasing physical distance between two countries by one standard deviation lowers trade in goods by 23%; the corresponding reductions for virtual and linguistic distances are 15% and 5%, respectively.

In addition to their direct effects, the measures of distance can amplify each other. In our paper, we show a negative sign interaction between geographical and virtual distance (except for FDI and banking positions). Physical distance leads to a larger contraction of international linkages in more distant country pairs, especially if the countries are also distant in virtual terms.

Evidence from the Covid-19 pandemic

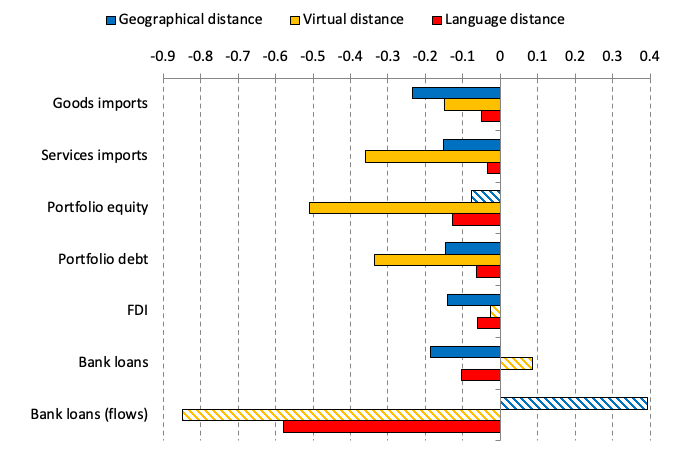

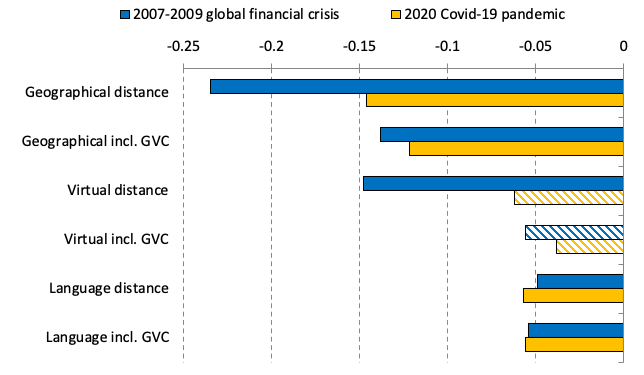

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic provides another case study during which international trade fell sharply. We therefore run a similar analysis on that episode, focusing on trade in goods due to data availability. Specifically, we regress the log change of imports between the first quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020 on our measures of distance. As the participation in global value chains (GVCs) has been a major development in the structure of trade in recent years (Alessandria et al. 2011), we also control for participation in GVC.

Figure 2 presents the estimated coefficient for the 2007-2009 Global Crisis (blue bars) and the Covid-19 pandemic crisis (yellow bars). In addition to the baseline estimates, it also indicates the estimates when controls for GVC participation are included. The estimates are similar across the two episodes, with geographical and language distance magnifying the contraction of trade in goods. Controlling for GVC participation reduces the impact of geographical distance in the 2007-9 Global Crisis, but not in the current episode. It also makes the impact of virtual distance non-significant, which suggests that being part of a value chain provides information that mitigates limits to communication.

Figure 2 Estimated effect of distance measures on imports of goods: Global Crisis vs. Covid-19 pandemic crisis

Note: The figure shows the estimated coefficients from regressing the log change on the imports of goods on the various measures of distance, controlling for the initial imports, gravity controls, source- and destination-country fixed-effects, and where indicated, controlling for GVC integration. The estimates are obtained for the 2007-2009 Global Crisis (blue bars) and the Covid-19 pandemic crisis (yellow bars). The measures of distances are standardised to ease comparison across coefficients, so the coefficients show the percentage impact of a one-standard deviation increase in distance. The solid and striped bars show significant and non-significant coefficients, respectively.

Evidence from a long sample

In addition to the specific episodes of sharply falling trade and financial positions, we take a longer-term view by assessing whether distance leads to more volatile economic linkages. We focus on trade in goods from 1950, and compute the standard deviation of the annual growth rate in bilateral imports over non-overlapping five-year intervals. These standard deviations are regressed on the various measures of distance and gravity controls in a panel setting.

We find that virtual distance is associated with more trade volatility when all measures of distance are included, though the limited availability of virtual distance shortens the time horizon of the analysis, and omitting it multiplies the sample size by a factor of four. Using a larger sample (without virtual distance), we find that geographical distance leads to more volatile trade flows, which is again in line with the footloose view.

Conclusion

Distance matters for international linkages, not only in terms of their levels – as is already established – but also in terms of their volatility and sensitivity to global conditions. A policy maker concerned about her country’s exposure to the global cycle should not focus only on her main trading partners, which are likely to be nearby countries. Trade flows with smaller distant partners could prove more volatile in crisis times and thereby contribute to overall trade volatility as much as more stable flows from neighbouring countries.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the ECB or the Eurosystem.

References

Alessandria, G, J Kaboski and V Midrigan (2011), “US Trade and Inventory Dynamics”, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 101(3): 303-307.

Anderson, J and E Van Wincoop (2003), “Gravity with Gravitas: a Solution to the Border Puzzle”, American Economic Review 93(1): 170-192.

Atkeson, A and A Burstein (2008), “Pricing-to-Market, Trade Costs, and International Relative Prices”, American Economic Review 98(5): 1998-2031.

Aviat, A and N Coeurdacier (2007), “The Geography of Trade in Goods and Asset Holdings”, Journal of International Economics 71: 22-51.

Baldwin, R (1988), “Hysteresis in Import prices: the Beachhead Effect”, American Economic Review 78(4): 773-785.

Berman, N, J de Sousa, P Martin and T Mayer (2012), “Time to Ship during Financial Crises”, VoxEU.org, 20 October.

Brüggemann, B, J Kleinert and E Prieto (2011), “A Gravity Equation for Bank Loans”, mimeo.

Chung, J (2011), “The Geography of Global Internet Hyperlink Networks and Cultural Content Analysis”, PhD Dissertation, University at Buffalo.

Galstyan, V and P R Lane (2013), “Bilateral Portfolio Dynamics during the Global Financial Crisis”, European Economic Review 57: 63-74.

Hellmanzik, C and M Schmitz (2016), “Taking Gravity Online: The Role of Virtual Proximity in International Finance”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.

Leamer, E (2007), “A Flat World, a Level Playing Field, a Small World After All, or None of the Above? A Review of Thomas L. Friedman’s The World is Flat”, Journal of Economic Literature 65: 83-126.

Mehl, A, M Schmitz and C Tille (2020), “Distance(s) and the volatility of international trade(s)”, CEPR Discussion Paper 13630.

Melitz, J and F Toubal (2019), “The Potential Impact of Machine Translation on Foreign Trade – Caution, Please”, VoxEU.org, 1 August.

Portes, R, H Rey and Y Oh (2001), “Information and Capital Flows: The determinants of Transactions in Financial Assets”, European Economic Review 45(4-6): 783-796.