The taxation of dividends strongly relies on withholding taxes (Milanez 2017). In particular, they are considered as a key instrument to combat evasion of savings taxation (Johannesen 2014). However, the use of withholding taxes opens opportunities for tax fraud, as the statutory bearer of the tax may be entitled to a tax refund even if no withholding tax has been remitted. While this is a notorious problem with value-added tax (VAT), known as the ‘missing trader’ fraud (Baldwin 2007), the problem recently showed up in the context of dividend taxation. Employing so-called ‘cum-ex’ transactions around ex-dividend dates, investors have received tax refunds while no dividend taxes were remitted. In 2017, a parliamentary investigation committee of the German Federal Parliament estimated a tax-revenue loss from cum-ex transactions exceeding £7 billion for the time period between 2005 and 2011 alone (Spengel et al. 2017).

How do these cum-ex transactions work? The basis is the dividend payment. The corporation withholds the dividend tax and pays the net-of-tax dividend to its shareholder via the depository bank. The shareholder obtains a withholding tax-certificate, which under certain conditions entitles the shareholder to a tax refund. Assuming a stock sale by the shareholder immediately before the ex-dividend date, a settlement procedure applies. Given the stock market guidelines, the stock can be delivered on the ex-dividend date even though the stock sale occurred cum-dividend – with dividend claim. To ensure that the buyer is not losing due to late delivery, the settlement arranges a ‘three-part delivery’ to the buyer: First, the seller delivers the stock ex-dividend. Second, the seller is required to pay the buyer a dividend compensation in the amount of the net-of-tax dividend. Third, the buyer's depository bank issues a withholding-tax certificate.

A cum-ex transaction combines the delivery of a stock after the dividend date with a short sale, i.e. the seller does not actually own the stock that is being sold. Instead, the stock is bought from a third party on the ex-dividend date. However, the settlement is unchanged ignoring the fact that the original owner, providing the stock for the short sale, has received not only the net-of-tax dividend but also a withholding-tax certificate. Consequently, the additional certificate provided due to the settlement procedure possibly entitles the buyer to a refund of taxes that were actually never remitted.

The case of cum-ex illustrates the importance of ‘who writes the cheque to the government’ (Slemrod 2008). Clearly, there is a deficiency in the remittance procedure, since it is the depository bank rather than the tax-remitting corporation which hands out the tax certificate. Beyond this technical point, however, it is remarkable how aggressive traders implemented cum-ex schemes in Germany. A prominent explanation, put forward in the media, is that traders searching for arbitrage opportunities simply exploited a tax loophole, or more precisely, the technical defect in the way the withholding tax was being imposed and administered. This is intuitive, since the traders' quest for arbitrage opportunities can be seen as some sort of discovery process that detects all types of profitable transactions. However, as we show in a companion paper (Buettner et al. 2020), this view is not consistent with the facts.

First, even if the buyer receives an illegitimate tax refund, cum-ex transactions that are placed separately in the regular order book are unlikely to be profitable for both short seller and buyer. This holds, in particular, under stock market conditions prevailing in the German market, where, as a stylised fact, stock prices on ex-dividend dates fall by the amount of the dividend.

(e.g. Haesner and Schanz 2013). Hence, given the asymmetric distribution of profits, cum-ex trading requires the short seller to share the profit with the buyer. In other words, the two parties need to collude.

Second, the actual developments of stock prices and number of traded stocks around dividend dates match well with the collusion hypothesis. We provide an empirical analysis based on a difference-in-difference approach. This is important since a large body of literature suggests that tax motivated trading and dividend-capturing strategies may give rise to higher trading activity around ex-dividend dates. The approach taken in the paper exploits differences in the tax treatment of dividends depending on whether dividends were paid out of reserves and on whether a transaction took place before or after the remittance procedure has been changed.

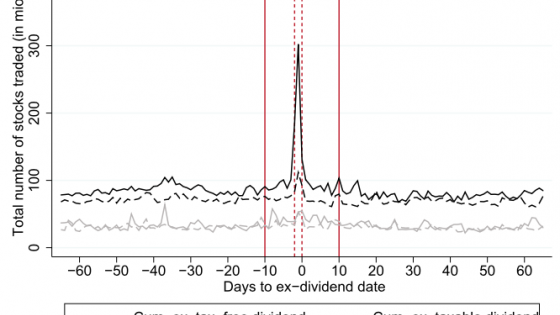

Based on XETRA data, we find that HDAX stocks with taxable dividends show a substantial increase in the number of stocks traded immediately before the ex-dividend date. This can be already seen in the raw data (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Daily average total number of stocks traded (XETRA data), 2009–2015

Notes: The figure depicts the daily average total number of stocks traded that were constituents of the German HDAX index between 2009 and 2015 as reported in the XETRA data. The trading volumes are separately presented for stocks with taxable dividends (black lines) and stocks with tax-free dividends (gray lines), both for the cum-ex period from 2009 to 2011 (solid lines) and the post period from 2012 to 2015 (dashed lines). The vertical dashed lines mark a 2-day window prior to the ex-dividend date. The vertical solid lines mark the 21-day trading window around the ex-dividend date. Source: Buettner et al. (2020).

Allowing for heterogeneity in the number of stocks traded among the 829 dividend events of HDAX companies in the time period under investigation, a regression analysis confirms significant increases in the number of stocks traded on the last two days before the ex-dividend date. In accordance with the collusion hypothesis, the empirical results also indicate that market-price effects are absent.

Further analysis shows that effects differ between trading venues showing much stronger increases of ‘over-the-counter’ transactions, where trades are particularly easy to arrange. The empirical patterns found also support the view that cum-ex transactions focus on stocks with high dividend yield and high market capitalisation, where the expected return is high and the risk of detection is low.

Given the evidence, withholding-tax non-compliance in the form of cum-ex transactions should not be regarded as some type of financial-market arbitrage exploiting a tax loophole. Rather, it is a form of deliberate tax fraud that requires collusion of short seller and cum-ex buyer in order to obtain an illegitimate tax refund. This has implications for tax policy and administration of withholding taxes.

It is interesting to note that, similar to the VAT's ‘missing-trader’ fraud, cum-ex tax fraud has emerged in an internationally integrated market environment, where inconsistencies between tax systems are exploited and where a lack of information makes effective enforcement difficult. Moreover, the large tax-revenue losses related to cum-ex tax fraud indicate that cum-ex buyer and short seller trade in an environment where it is relatively easy to collude. This is remarkable, given the close regulation and supervision of financial markets and of the agents participating in these markets including banks. The academic literature has emphasised that firms often play a very constructive role for tax administration. More specifically, firms serve as fiscal intermediaries providing information as well as remitting withholding taxes (Kleven et al. 2016). An important precondition is that the agent providing information and/or remitting the tax and the agent, who is the statutory bearer of the tax, face difficulties to form a stable collusion. The cum-ex case, however, shows that banks are rather imperfect fiscal intermediaries for dividend taxation. To improve compliance, further action is required to make it more difficult to collude.

References

Baldwin, R (2007), “EU VAT fraud part 3”, VoxEU.org, 17 June.

Buettner, T, C Holzmann, F Kreidl and H Scholz (2020), “Withholding-Tax Non-Compliance: The Case of Cum-Ex Stock-Market Transactions”, International Tax and Public Finance, online first.

Haesner, C and D Schanz (2013), “Payout policy tax clienteles, ex-dividend day stock prices and trading behavior in Germany: The case of the 2001 tax reform”, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 40(3-4):527–563.

Johannesen, N (2014), “Tax evasion and Swiss bank deposits”, Journal of Public Economics 111:46–62.

Kleven, H J, M B Knudsen, C T Kreiner and E Saez (2016), “Why can modern governments tax so much? An agency model of firms as fiscal intermediaries”, Economica 83(330):219–246.

Milanez, A (2017), “Legal tax liability, legal remittance responsibility and tax incidence: Three dimensions of business taxation”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, 32.

Slemrod, J (2008), “Does it matter who writes the check to the government? The economics of tax remittances” National Tax Journal 61(2):251–275.

Spengel, C, V Dutt and H Vay (2017), “Auswertung der Clearstream Beweismittel-Zulieferungen”, Auswertung für den 4. Untersuchungsausschuss der 18. Wahlperiode. Deutscher Bundestag, Berlin.