The impact of policy uncertainty on economic activity is an issue traditionally associated with developing countries. Since 2008, however, the spotlight has shifted. Governments’ responses to the Great Recession and the Eurozone crisis have raised considerable uncertainty about the future policies of advanced economies. Examples include the timing and size of financial bailouts, government expenditures, and the risk of sovereign-debt default. These crises have also heightened trade policy uncertainty. The Great Recession generated widespread fear of a global trade war, and the European crisis has the potential to reverse free trade policies on the continent as countries consider exiting from the euro (e.g. Greece) or the EU altogether (e.g. the UK).

Uncertainty is especially important for a firm making irreversible investments to enter a market, adopt a technology, or restructure its labour force. Such firms may optimally delay investment until current conditions improve or uncertainty is resolved. The theoretical impact of uncertainty on some firm investments is understood (see for example Bernanke 1983, Baldwin and Krugman 1989, and Dixit 1989). There is also some empirical evidence linking the two (Bloom et al. 2007 and Bloom 2009). Unfortunately, there is scarce empirical evidence on the impacts of policy uncertainty, because it is both hard to measure and difficult to identify its impact on specific economic outcomes (Rodrik 1991). One approach is to construct news-based indices of economic policy uncertainty. While such indices contain useful variation over time, they are insufficient to clearly identify causal effects of policy uncertainty on firms.1

Policy uncertainty and international trade

In recent research, we argue that firms’ international trading decisions are useful in overcoming those measurement and identification issues for three reasons:

- First, we observe the applied policies that firms face in different markets (e.g. tariffs) and the counterfactual worst-case values, which helps us measure policy uncertainty.

- Second, we can tie those policies to certain observable firm outcomes by product and destination to establish a causal relationship (e.g. market entry, sales, and quantities).

- Third, there are many trade reforms that allow us to answer whether and how governments and international institutions can affect policy uncertainty.

Understanding policy uncertainty in trade is also important in its own right. Globalisation implies that trade policy uncertainty has a direct effect on an increasing number of firms that export, use imported intermediates, and offshore parts of their production process. Uncertainty can directly affect firms’ investments to enter markets, adopt new technologies, or offshore. Via the trade channel, uncertainty can also indirectly affect purely domestic firms (and consumers) by changing domestic prices, productivity, and employment. While the WTO and its predecessor, the GATT, have long emphasised its role in maintaining “predictability through bindings and transparency [to] promote investment”, until recently there was no evidence for this channel.2

Policy uncertainty and China’s WTO accession

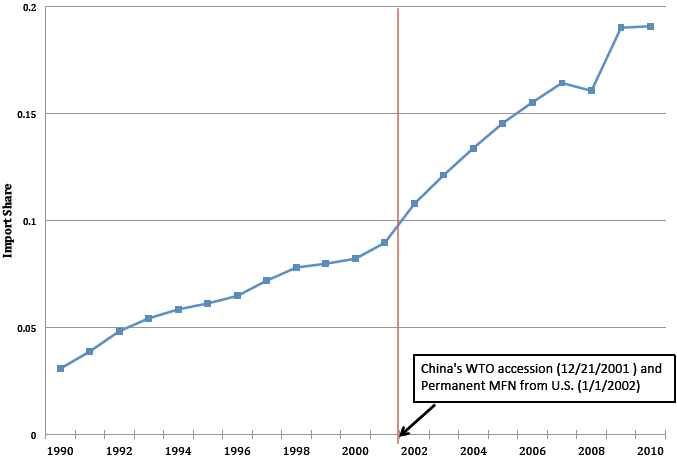

In Handley and Limão (2013), we analyse the impact of policy uncertainty on China’s export boom. China accounted for only 2% of the world’s imports in 1990, but its rapid growth, export-led policies, and possibly its WTO accession propelled that share to 11% in 2010. The share of US imports from China in that period rose even faster – from 3% to 19% – and recent evidence has linked this recent export boom to declines in US prices, wages, and manufacturing employment.3

Figure 1. Chinese share in US imports 1990-2010

Figure 1 uses US Census data to show that this country’s import share grew twice as fast in 2001–2010 as in 1990–2000. This acceleration coincided with China's WTO accession, which appears initially puzzling since there were no significant changes in applied trade barriers in the US. What did change was the uncertainty Chinese firms faced about future US policies. More specifically, since 1980, China enjoyed most-favoured nation status in the US. This meant China faced tariffs similar to WTO members exporting to the US, with a key difference – China’s status was subject to uncertain renewal.

While China never lost most-favoured nation status, it came close. After the Tiananmen Square protests, the US Congress voted on such a bill every year until 2001, and the House passed it three times. Had the status been revoked, the average US tariff would have increased from 4% to 35%. Many products would have faced tariffs as high as 50%, and this would likely have sparked a trade war. Policymakers and firms in both countries understood the potential effects of this uncertainty. In 1997, the Chinese Foreign Trade Minister urged the US to abandon the most-favoured nation status reviews because “[It] has created a feeling of instability among the business communities of the two countries and has not been conducive to bilateral trade development”.4 Several industries lobbied the US congress prior to 2001 to make most-favoured nation status permanent, and argued that “the imposition of conditions upon the renewal of most-favoured nation [is] virtually synonymous with outright revocation. Conditionality means uncertainty.”5 But it was only in January 2002 – after WTO accession – that the US president granted permanent most-favoured nation status, which according to the Chinese foreign Ministry “eliminated the major long-standing obstacle to the improvement of Sino-US [...] economic relations and trade.”6 7

The timing of China’s WTO accession and the actions of policymakers and businesses regarding most-favoured nation status are necessary conditions for trade policy uncertainty to help explain the observed export boom, but they are clearly not sufficient – China could have started growing faster or investing more in export industries for other reasons. Therefore, we model the impact of trade policy uncertainty on entry and technology upgrading to serve the US market at the firm level. These investments depend on the probability that China loses most-favoured nation status and the ensuing reduction in profits. In Handley and Limão (2013), we construct that loss measure from the observable most-favoured nation and the worst-case scenario Smoot-Hawley tariffs. The model predicts that industries with higher potential losses will have lower exports, and will thus grow faster if WTO accession removes this source of uncertainty.

The data show that in 2000 to 2005, Chinese export growth to the US was 18% higher in industries where the potential profit loss was initially high than those in which it was low. Because changes in tariffs and transport costs are very small, they cannot explain this differential growth – but other factors could. So, to clearly identify the effect of policy uncertainty, we employ regression analysis. Our main empirical findings are the following:8

- Prior to WTO accession, Chinese exporters placed a positive probability on losing most-favoured nation status in the US. The accession substantially reduced this probability and generated stronger export growth in industries that initially faced higher potential losses.

- The reduction in policy uncertainty increased China’s aggregate exports to the US between 22% and 30%. This is equivalent to an average reduction in applied tariffs of up to nine percentage points.

- There were higher product entry rates in industries with initially higher potential profit losses.

- The uncertainty reduction lowered aggregate prices in the US, which translates into a substantial real income increase for its consumers. We therefore quantify an effect of trade agreements thus far ignored – they can increase welfare by reducing uncertainty.

Additional impacts of trade agreements on policy uncertainty and broader implications

These findings in the context of US–China trade are consistent with our previous work in other settings. In Handley and Limão (2012), we study agreements that secure preferential market access for developing countries in the context of Portugal’s accession to the European Community in 1986. We find this accession reduced the trade policy uncertainty faced by Portuguese firms, and induced large numbers of them to make investments to start exporting to the European Community. Handley (2012) examines the value of tariff ceilings negotiated in the WTO, and finds that reductions in those ceilings increase trade even if they are above the applied tariffs and the latter remain unchanged. This provides a mechanism that has been neglected in the empirical debate on whether the WTO does increase trade.

In summary, this research provides a framework to measure and estimate the impacts of policy uncertainty on firm decisions and finds it has strong effects in the context of international trade . Large-scale trade reforms provide a rich source of data on policy that varies over time, countries, and products, and can be used to establish a causal link between trade policy uncertainty and firm decisions. More broadly, some of the methodological insights and evidence from this recent research may be useful in understanding how uncertainty in other policy instruments (e.g. domestic taxes) and other settings (e.g. the potential exit of Greece or the UK from the EU) can reduce economic activity and welfare.

References

Auer, R A and A M Fischer (2010), “The effect of low-wage import competition on US inflationary pressure”, Journal of Monetary Economics 57(4): 491–503.

Autor, D, D Dorn, and G Hanson (Forthcoming), “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the US”, The American Economic Review.

Bagwell, K and R Staiger (1999), “An Economic Theory of GATT”, The American Economic Review 89(1): 215–248.

Baker, S, N Bloom, and S Davis (2012), “Has Economic Policy Uncertainty Hampered the Recovery?”, Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics Working Paper 2012-003.

Baldwin, R and P Krugman (1989), “Persistent Trade Effects of Large Exchange Rate Shocks”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 104(4): 635–654.

Bernanke, B S (1983), “Irreversibility, Uncertainty, and Cyclical Investment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 98(1): 85–106.

Bloom, N (2009), “The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks”, Econometrica 77(3): 623–685.

Bloom, N, S Bond, and J V Reenen (2007), “Uncertainty and Investment Dynamics”, Review of Economic Studies 74(2): 391–415.

Dixit, A K (1989), “Entry and exit decisions under uncertainty”, Journal of Political Economy 97(3): 620–638.

Handley, K (2012), “Exporting under Trade Policy Uncertainty: Theory and Evidence”, University of Michigan Working Paper.

Handley, K and N Limão (2012), “Policy Uncertainty, Trade and Welfare: Theory and Evidence for China and the US”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9615.

Handley, K and N Limão (2012), “Trade and Investment under Policy Uncertainty: Theory and Firm Evidence”, CEPR Discussion Paper 8798.

Limão, N and G Maggi (2013), “Uncertainty and Trade Agreements”, CEPR Discussion Paper 9301.

Pierce, J R and P K Schott (2012), “The Surprisingly Swift Decline of US Manufacturing Employment”, NBER Working Paper 18655.

Rodrik, D (1991), “Policy Uncertainty And Private Investment In Developing Countries”, Journal of Development Economics 36(2): 229–242.

Rose, A K (2004), “Do We Really Know That the WTO Increases Trade?”, The American Economic Review 94(1): 98–114.

Subramanian, A and S-J Wei (2007), “The WTO promotes trade, strongly but unevenly”, Journal of International Economics 72(1): 151–175.

1 Baker et al. (2012) construct such an index and find it is useful in predicting aggregate declines in output and employment.

2 Bagwell and Staiger (1999) provide a theory of how the GATT/WTO functions to internalise the terms-of-trade effect imposed by tariffs. Limão and Maggi (2013) broaden this work to include gains from reducing uncertainty.

3 Auer and Fischer (2010), Autor et al. (Forthcoming) and Pierce and Schott (2012).

4 “Minister urges USA to abandon trade status reviews”, Xinhua news agency, 5 October 1997, FE/D3044/G.

5 China Most-Favored-Nation Status, “Hearing before the Committee on Finance”, US Senate, 6 June 1996, p. 97.

6 The president was required to determine whether the terms of China’s WTO accession satisfied its obligations under the Act. Otherwise the US could opt out of providing most-favoured nation status to China under Article XIII of the WTO – a right it had exercised with respect to other members of the WTO.

7 “China–US trade volume increases 32 times in 23 years – Xinhua reports”, BBC Summary of World Broadcasts, 18 February 2002.

8 For details on the identification approach and the extensive robustness tests, see Handley and Limão (2013).