The origins of short-run fluctuations in macroeconomic variables, such as output and investment, are a seminal problem in macroeconomic research according to Kocherlakota (2009) and many others. Over time, a large literature has addressed this question by adopting multiple approaches. In a recent handbook chapter, Ramey (2016) provides an overview of different methods to isolate macroeconomic shocks, the “primitive, exogenous, and economically meaningful forces” that buffet the economy and cause business cycles. Among others, these approaches include structural vector autoregressions, dynamic factor models, estimated dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models, and narrative methods. These techniques have been applied to investigate the effects of technology, fiscal, or monetary policy shocks, and other disturbances, on macroeconomic variables.

A survey-based narrative approach

In a recent paper, we pursue a novel and complementary approach building on unique firm-level survey data (Bachmann and Zorn 2018). The ifo Investment Survey from the Munich-based ifo Institute asks decision makers in German manufacturing firms about the importance of sales, technological factors, finance, return expectations, and macroeconomic policy as determinants of their investment activity in a given year. We estimate macroeconomic shocks from this subjective reason data. Methodologically, our survey-based narrative approach is close in spirit to Bewley (1999), who interviews managers in firms to investigate the sources of downward nominal wage rigidity.

The advantage of this approach towards identifying shocks lies in its putative directness – the survey respondents directly report whether their investment activity in a given year was influenced by, for instance, technological factors, and, if so, how strongly. As a result, shock identification is less prone to be confounded by other factors. In this regard, our approach is similar to other narrative methodologies that have been used in empirical macroeconomics to study the effects of macroeconomic policies (Romer and Romer 2004, 2010), but also extends to shocks unrelated to macroeconomic policy.

Aggregate demand shocks as the main driver of the business cycle

Importantly, the survey investment determinants have highly plausible economic content:

- The sales investment determinant is highly correlated with new manufacturing orders.

- The technological investment determinant is correlated with the prevalence of restructuring and rationalisation investment, as well as process innovations carried out at the firm level.

- The finance investment determinant is related to independent measures of external finance dependence at the firm level, and, over time, to credit spreads and proxies of idiosyncratic business uncertainty.

Finally, in line with simple economic theory, we show that firms for which the sales determinant is important for their investment behaviour are more likely to increase prices and less likely to decrease them; and vice versa for the technological determinant.

Figure 1 Aggregate investment determinant indices

Using the firm-level survey responses, we construct index measures of the importance of each investment determinant in the manufacturing sector. Figure 1 plots these aggregate investment determinant indices over time, ranging from -2 (strongly negative influence), to 0 (no influence), to +2 (strongly positive influence). Two observations stand out.

- First, in contrast to the other investment determinant indices, which often fluctuate around zero, the effect of technology on capital expenditures is positive throughout. This observation is consistent with the neoclassical view that technological factors determine investment on average and in the long-run.

- Second, the effect of sales (and return expectations) has a clear cyclical pattern, stronger than any of the remaining investment determinants, finance, macroeconomic policy, and the residual category ‘Other’.

In our paper we also show that, for most firms at any given point in time, finance, macroeconomic policy, and ‘Other’ play no role in their investment decisions (Bachmann and Zorn 2018). Finally, a correlation analysis for the aggregate investment determinants reveals that these indices are (imperfectly) correlated with each other and aggregate investment, which means, that we cannot interpret the investment determinants directly as shocks.

We argue, however, that in Germany, aggregate demand shocks and aggregate technology shocks are the only plausible candidates for explaining aggregate investment fluctuations, and we therefore make them the main focus of our strategy to identify orthogonal aggregate shocks from the narrative determinant series. To disentangle these two shocks in the data, we impose correlation restrictions that rely on the informational content of the narrative series and simple economic theory. Specifically, we require that the identified aggregate demand shocks are highly correlated with the sales investment determinant, and likewise for the identified aggregate technology shocks and the technological factors investment determinant. In addition, in many standard models, aggregate demand shocks and aggregate technology shocks have different implications for prices. In particular, producer price inflation should be positively correlated with aggregate demand shocks while its correlation with technology shocks should be negative, and we impose these implications for identification.

To gauge their importance in short-run fluctuations, we relate our identified aggregate demand and aggregate technology shocks to aggregate investment growth (and also aggregate output growth).

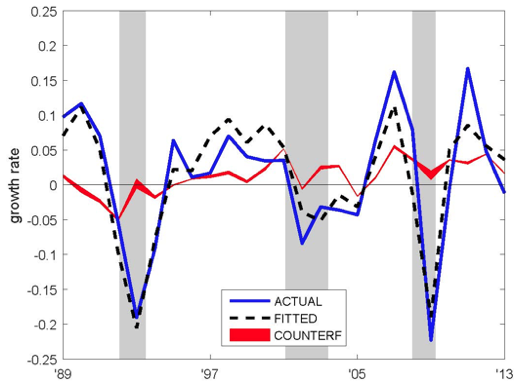

Figure 2 Fit and counterfactual

We find that a considerable portion (81%) of the total variance of aggregate investment growth can be explained by our survey-based subjective investment determinants and the orthogonal shocks extracted from them. This result again shows the high quality of these survey data, and, more generally, also lends credence to our survey-based narrative approach. Second, we find that approximately two thirds of the total variance of aggregate investment growth can be explained through aggregate demand shocks. Aggregate technology shocks play only a minor role. As Figure 2 shows, this finding is also confirmed in a counterfactual simulation of the post-reunification German aggregate investment rate – almost none of the officially declared recession years for Germany would have experienced negative investment growth without the aggregate demand shocks, in contrast to the data. The reunification boom would not exist, neither would the prolonged slump in the early 2000s. There would have been no investment boom nor a rebound around the Great Recession. In other words, without aggregate demand shocks, the aggregate investment growth rate series would not align with the German post-reunification business cycle. Aggregate demand shocks are thus essential for our understanding of this business cycle.

Aggregate demand shocks resemble business and consumer sentiment

What are these aggregate demand shocks that we identify as determining the bulk of aggregate investment fluctuations? Our research provides a negative and a positive answer to this question.

First, we show that our identified aggregate demand shocks are unlikely to be the result of misclassification of industry-specific technology shocks that spill over to other industries where they are merely perceived as demand shocks – for instance, one small manufacturing industry (which procures large amounts of input goods from other upstream manufacturing industries) could have a positive technology shock followed by increased input demand for other manufacturing industries, which would lead to higher demand-related investment there. Alternatively, consider a large manufacturing industry that makes an invention that is sold to downstream industries. It might classify a technological shock as increased demand for its products. We investigate both channels and conclude that none appears quantitatively relevant. Moreover, an industry-level analysis shows that in most manufacturing industries the aggregate pattern – demand shocks explain the bulk of investment growth volatility – replicates itself at the more disaggregate level. That is, our aggregate results are not due to a mere composition effect.

Second, we use manufacturing business sentiment and consumer sentiment data to argue that our identified aggregate demand shocks, which correlate well with these standard sentiment measures, are good candidates for sentiment or animal spirit shocks. By contrast, with the one and clear exception of the post-reunification monetary tightening in Germany by the Bundesbank and the immediate subsequent recovery, no obvious demand stabilisation policy instrument has any association with our identified aggregate demand shocks.

References

Bachmann, R and P Zorn (2018), “What drives aggregate investment? Evidence from German survey data”, CEPR Discussion Paper 12710.

Bewley, T (1999), Why Wages Don’t Fall During a Recession, Harvard University Press.

Kocherlakota, N (2009), “Modern macroeconomic models as tools for economic policy”, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Annual Report Essay.

Ramey, V (2016), “Macroeconomic shocks and their propagation”, in J Taylor and H Uhlig (eds), Handbook of Macroeconomics 2A: 71–162, Elsevier.

Romer, C D and D H Romer (2004), “A new measure of monetary shocks: Derivation and implications”, American Economic Review 94: 1055–1084.

Romer, C D and D H Romer (2010), “The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: Estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks”, American Economic Review 100: 763–801.