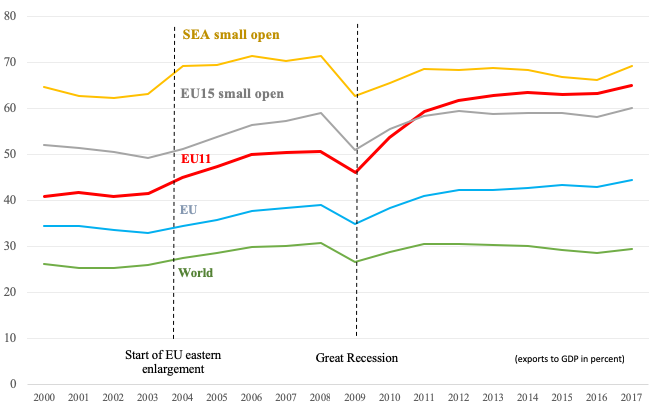

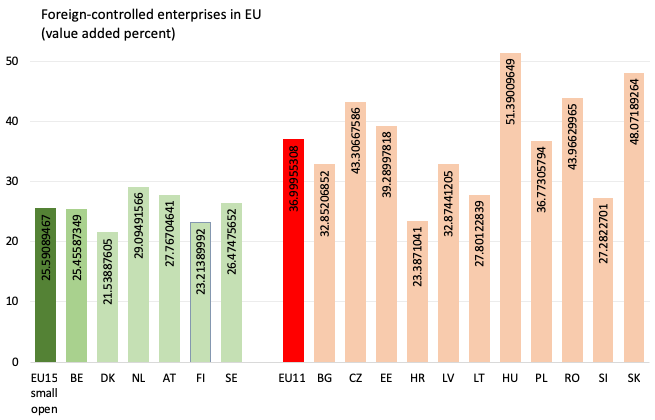

Today, EU11 economies1 are among the most open economies globally (Figure 1). Their degree of trade openness has increased and the nature of their trade flows has changed rapidly in this millennium in large part because they joined the EU.

Other factors also contributed, such as the reform driven by their transition from central planning to market economies and their preparation for EU membership, as well as global trends that led to the emergence of global value chains (GVCs) in this period.

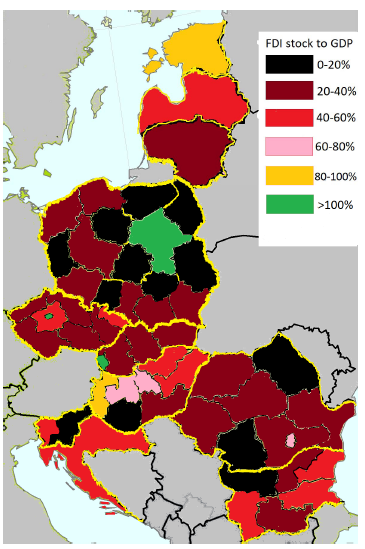

Figure 1 Export openness

Source: World Bank

Note: EU15 small open includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland Netherlands and Sweden. SEA small open includes Cambodia, Korea, Malaysia and Vietnam. EU11 includes Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

The unusual nature of the EU11

However, important characteristics of EU11 countries differ from those of other countries with similar degrees of trade openness. Their institutions and their social support systems are less developed than those of small open EU15 countries, and their households have less financial savings to smooth their consumption. As the capacity of an economy to absorb shocks and manage structural changes depends greatly on the quality of its institutions and social support system, this is an important difference within the EU.

On the other hand, similarly open lower-middle income countries in other parts of the world are not part of a supra-national organisation like the EU. They have not adopted the institutional and legal systems of highly developed countries, and they are not part of a single market with free movement of capital and labour. As trade flows are significantly influenced by the decisions of firms on the location of their production and labour migration, these characteristics of EU11 countries are highly relevant if we want to understand how trade and other shocks impact them.

EU11 countries show many important similarities when it comes to trade integration, most importantly the large share of intra-EU trade and its implications for growth and development. Nevertheless, there are also important differences among these countries regarding their level of development, the composition and quality of their exports, and the degree to which they participate in GVCs.

While most economist would agree on the positive economic effects of closer trade integration at the aggregate level, there is an increasing awareness of the importance of other aspects, such as:

- income distribution and more broadly equal chances and fairness (Milanoviċ 2016, OECD 2019),

- agglomeration effects and the resulting regional disparities and the increasing prices of housing and regional labour market mismatch (EBRD 2018, Ossa 2019),

- labour migration and the resulting fiscal and social implications (Andor 2019), and

- more lasting impact on societies than previously experienced (Buti 2019).

Understanding the impact of shocks

The recent crisis in Europe demonstrated that the focus on narrowly defined aggregate economic growth and economic resilience is not sufficient to understand the longer-term impact of economic shocks. These shocks stimulate growth but can also trigger a crisis. A broader focus that entails social and political aspects is necessary to understand current developments and to formulate adequate polices (Székely 2019). Put differently, it also matters who benefits and who loses out from rapid trade integration and convergence, who absorbs the hits during a crisis and how, as well as how different groups in society – winners and losers – and society as a whole react to the challenges trade integration brings about.

If left unaddressed, negative social trends created by market forces can reverse reforms, and ultimately lead to an erosion of growth potential and economic resilience (Székely and Ward-Warmedinger 2018). They can also have major implications for political developments at the national and the European level. These may prevent the deepening of European integration.

Global value chains

The emergence of GVCs (Baldwin 2012, Baldwin and Obuko forthcoming) changed the nature and impact of trade integration. Intra-regional value chains currently predominate (Antras and De Gortari 2017). But as trade costs fall, the global (including European but extra-EU) component of value chains is likely to increase. Similarly, as the service component of GVC increases rapidly, competitive pressure from global markets increases.

GVCs, particularly their service component, are strongly impacted by disruptive technological innovation, with major impact on the skill structure of labour demand. This leads to a constant relocation of the different elements of GVCs. This possibly means reshoring certain parts to EU15, but also offshoring of core elements from EU15 to EU11 or to countries outside the EU (Mayer and Head forthcoming). This trend is likely to strengthen in the future.

An inflow of FDI

Trade integration and the creation of GVCs also drove the inflow of FDI into EU11 countries. Imports of modern technology and capital deepening, as well as a rapid modernisation of the product structure, had a positive impact on productivity of local suppliers (Harding and Smarzynska Javorcik 2011, Hagemejer and Muck forthcoming). This confirms the empirical analysis in Alfaro and Chen (2012), which shows that multinational production causes both knowledge spillovers and factor reallocation in domestic markets. Policies that make this more likely include improving credit access and labour supply (particularly skilled labour) while eliminating regulatory barriers. These are typical of reforms in EU11 countries.

As with trade, many of the underlying forces that promoted FDI were global. Geographical proximity helped, but EU accession provided fertile ground for these forces to work, as it helped improve institutions and create a higher degree of legal certainty for investors (Buiter and Lubin 2019). EU11 countries benefited significantly from the reduction of barriers to trade. Merlevede and Purice (2019) have estimated that supplying inputs to a multinational just across the border enhances productivity only when countries share an EU border. These spillover effects become even stronger when borders become seamless, as is the case in the Schengen Area.

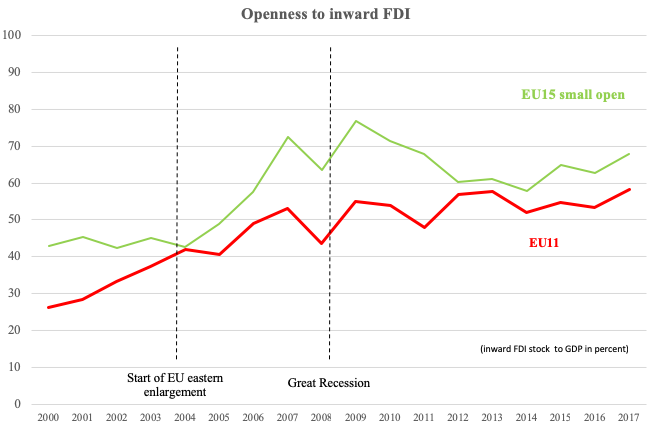

As a result, inward FDI (excluding special purpose entities, or SPEs) relative to GDP in EU11 countries has caught up with the trend observed in the most developed small open economies in the EU and in the world (Figure 2). The same however has not been true for outward FDI.

Figure 2 Stocks of Inward and outward FDI in small open EU15 and EU11 countries

Source: UNCTAD.

Note: EU15 small open includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland Netherlands, and Sweden; EU11 includes Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. Unweighted group averages.

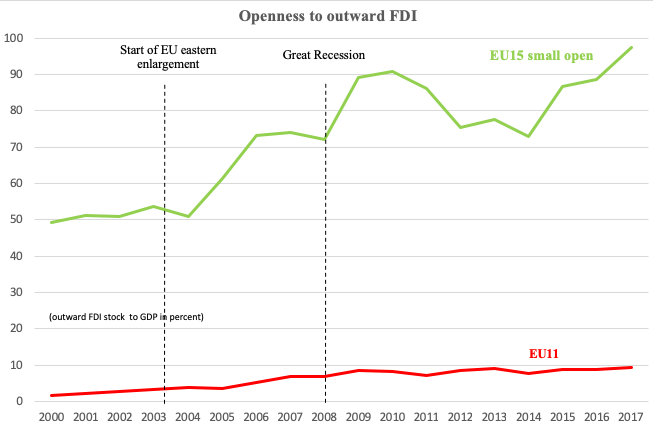

As the overall capital stock relative to GDP is smaller in EU11 than in EU 15 countries, the share of FDI in total stock of capital is higher (Figure 3). Put differently, foreign capital, and thus foreign influence in the corporate sector, is more important in these countries – particularly in their export (tradable) sector. The technological sophistication of FDI is also significantly above the rest of the economy. A large part of R&D takes place in these companies, and they employ a higher share of skilled labour than their share in the private economy.

Figure 3 Value added produced by foreign-controlled enterprises

Source: Eurostat.

Note: EU15 small open includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland Netherlands, and Sweden; EU11 inlcudes Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. Unweighted group averages.

Proximity to Germany, where companies were among the first in the EU to create of GVCs, and to other main European markets, and their abundance of low-cost but relatively skilled labour, made EU11 countries perfect targets for integration into European (mostly German) global value chains. They were in the right place, at the right time, in the right condition to benefit from this global process. The closer to the centre of gravity and the better the transport infrastructure, the more so, even within countries. Export-oriented companies, particularly those that are part of a GVC, are predominantly foreign-owned and highly concentrated in certain regions.

Increasing FDI has further accelerated the already strong agglomeration effects and increased the demand for higher skills, and the wage premium they command. FDI is highly concentrated in main urban areas, particularly in capitals and in areas that are close to the main west European manufacturing firms creating GVCs (Szabo 2019).

Figure 4 Regional differences in inward FDI in EU11 countries

Source: Statistics of national central banks and/or national statistical institutes.

Economic responses during the crisis: A model-based simulation

One of the salient characteristics of the crisis experience of EU11 countries was that, in many of these countries, the decline in domestic demand has been much bigger relative to the decline in GDP than in the core EU countries. Reasons include credit-driven consumption, and a real estate boom in the run-up to the crisis. At this stage, the real estate boom seems unlikely to be repeated, though in some countries household credit and house prices have picked up sharply.

With the help of calibrated DSGE models, we can pinpoint two important characteristics of EU11 countries that can explain a large part of this phenomenon, and will remain relevant moving forward:

- A large share of foreign ownership of productive capacities, without a comparable magnitude of outward FDI.

- A large share of hand-to-mouth consumers – that is, people who have little savings and thus have to live on their current income. This is partly a consequence of the first characteristic.

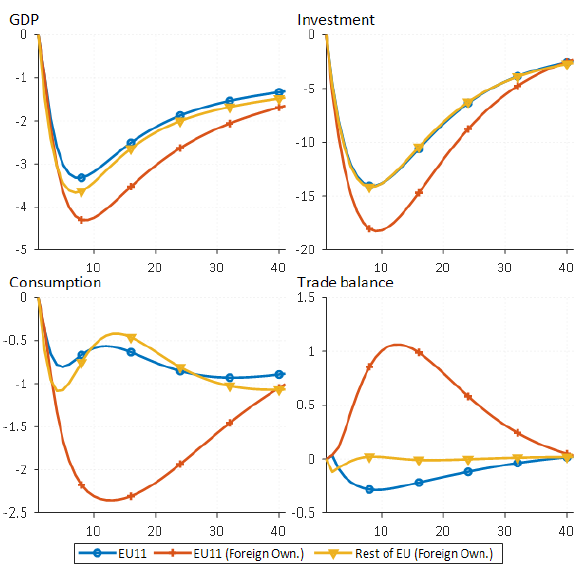

As the charts in Figure 5 show, these characteristics have important implications for how the economy reacts to a global recessionary shock in an EU11 country with high foreign ownership of productive assets relative to an EU15 country, and relative to the hypothetical case of an EU11 country without sizable foreign ownership. Regarding the former comparison, which is more relevant to understanding recent and future economic developments in EU11 countries, domestic demand – particularly consumption – declines more sharply. The decline in investment is bigger, reflecting the accelerator effect of higher consumption decline. Since exports follow similar paths, trade balance paths are very different.

Figure 5 Response to a recessionary shock in EU11 countries, with and without major foreign-ownership of productive capital

Source: Economic Commission, DG ECFIN staff calculations using Quest model.

Note: QUEST models calibrated to EU11 and rest of EU countries. The model used for EU11 (Foreign Own.) assumes a high share of foreign ownership of productive capacities in EU11 countries. Models assume flexible exchange rate regimes.

Given the high share of non-tradables in consumptions, a much larger decline in consumption, which is not fully passed on to imports, implies that non-tradable sectors decline much more in an EU11 economy with sizable foreign ownership. Moreover, despite relatively flexible labour markets, hysteresis is still significant. Equally importantly, investments recover more gradually.

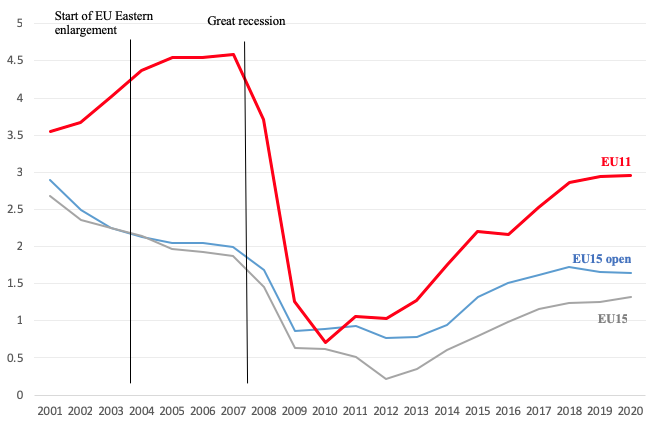

In short, growth potential may be reduced more. Thus, not only actual production but also potential output can be more volatile than in more matured economies. As Figure 6 shows, this matches real life.

Figure 6 Potential output growth, 2001-2018

Source: AMECO.

Note: EU15 small open includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland Netherlands, and Sweden. EU11 inlcudes Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

Adjustment to shocks

A crisis tends to accelerate the relocation of production and reorganisation of GVCs as it puts renewed pressure on multinational firms to reduce costs (Zlate 2016). As Figure 1 showed, after the initial shock, EU11 countries benefited from the relocation effect in the recent crisis because their export openness increased significantly after a temporary crisis-related decline.

Summing these two effects (a bigger shock to the non-tradable sector and a renewed reallocation of modern export-oriented production to EU11 countries), winners win more and losers lose more. The growth potential at the aggregate level may have been largely restored, but the vulnerabilities have increased. In the absence of an efficient state with high-quality public expenditure and social support system, this may destabilise societies and domestic politics. Reversals in reforms in the region is a likely manifestation of this impact (Székely and Ward-Warmedinger 2018).

In Figure 5, the models incorporated exchange-rate flexibility. Flexible exchange rate regimes, especially when they are allowed to work, help absorb external shocks, and can be particularly helpful when external shocks are asymmetric. Model simulations confirm this. Without this, volatility in output increases.

Joining the euro area takes away the exchange rate as an adjustment tool, but EU11 countries that have joined the euro area had given up this tool beforehand. A major part of the excess output volatility in these countries during the recent crisis was related to the excessive macroeconomic imbalances that had been accumulated in the boom years prior to the crisis.

The focus should be on avoiding this in the future. In fact, the Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure, and more broadly surveillance under the European Semester process, should help.

Some EU11 countries have not yet joined the euro area or expressed interest to do so. They have floating rates as an adjustment tool at their disposal. It served them well during the crisis (IMF 2016), though of course could not eliminate the consequences of poor policies.

With foreign exchange-denominated loans greatly reduced, they can use exchange rate flexibility more than before the crisis. But, as in the crisis, exchange rate flexibility will not be a panacea for poor macroeconomic policies and lack of structural reforms. Just the opposite – with poor polices, the volatility of the exchange rate can well aggravate the situation.

Policy options

Policy options to react to trade shocks can range from the short-termism of protecting rents tied to vested interests, to longer-term strategies of adopting appropriate structural reforms and enhancing the quality of institutions. Structural reforms may help the economy to remain an attractive investment destination, or move up the value chain, leap-frogging others. Currently we see both these responses.

Trade protectionism of any form would be particularly detrimental for EU11 countries (Vandenbussche et al. 2017), and their policymakers understand this well. Less well understood by them is that restrictions on FDI in their non-tradable sectors (such as retail trade) and sectors that are yet less exposed to competition from the outside (certain service sectors) also reduce their competitiveness and capacity to attract FDI in the tradable sector (Blanchard 2006).

We know the reforms – accelerate human capital accumulation, improve the business environment, strengthen institutions, reduce corruption – that would make a lower-middle income country a more desirable destination for FDI and domestic private investment to enhance their growth potential (EBRD 2019, Berglof et al. 2019). These standard reforms help improve allocative efficiency and innovation. The country-specific recommendations issued to these countries as part of the European Semester process reflect this well (European Commission 2018), and similar recommendations are given to these countries by other international organisations, such as the IMF, the World Bank, the EBRD, or the OECD.

Less emphasised is the need to strengthen local firms, to help them to become European or global firms, invest abroad, and thus create more symmetry between inward and outward FDI in EU11 countries.

But success on this front may also make EU11 countries more vulnerable to external shocks (Deltuvaitė 2017). Therefore, the right balance and sequencing of reforms is needed to make their convergence not only fast but also sustainable – economically, socially and politically. Given their strong exposure to global shocks, social policy reforms should address all three dimensions – pre-, in- and post-market – to make EU11 countries more socially, and thus politically, more resilient. Institutional reforms are key on all fronts, and can also help to build capacity and use EU funds more efficiently.

Reforms at the EU level that can mitigate the negative impact of outward labour migration on national social security systems, and reforms that can help EU11 countries to strengthen their unemployment systems and diversify away risk related to labour income, are such important areas (Andor 2015, Andor and Pasimeni 2016).

Continued capital imports will remain a necessary element of a development strategy, and risk diversification is essential for such small and highly specialised open economies. The crisis clearly demonstrated the vulnerabilities of debt financing. Thus, reforms that can reduce these vulnerabilities, such as the completion of the Banking Union (which is important also for EU11 countries outside the euro area as their banking sectors are dominantly owned by banking groups in the euro area). Reforms that can make alternative source of finance more easily available, such as the completion of the Capital Market Union, are also an essential part of such a strategy.

References

Alfaro, L, and M X Chen (2012), "Surviving the Global Financial Crisis: Foreign ownership and establishment performance", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4(3): 30-55.

Andor, L (2015), "Fair Mobility in Europe", Social Europe occasional paper 2015.

Andor, L (2019), "EU enlargement: the social dimension. Human capital and East-West imbalances": 9-15 in I P Székely (ed) Faces of Convergence, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies.

Andor, L, P Pasimeni (2016), "An unemployment benefit scheme for the Eurozone", VoxEU.org 13 December.

Antràs, P, and A De Gortari (2017), "On the geography of global value chains", NBER working paper 23456.

Baldwin, R (2012), "Global Value Chains: Why they emerged, why they matter, and where they are going", CEPR Discussion Paper 9103.

Baldwin, R, and T Okubo (forthcoming), "GVC journeys: Industrialisation and Deindustrialisation in the Age of the Second Unbundling", Journal of The Japanese and International Economies.

Berglof, E, S Guirev, and A Plekhanov (2019), "The convergence miracle in Eastern Europe: Wil it continue?": 19-27 in I P Székely (ed) Faces of Convergence, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies.

Blanchard, O (2007), "Adjustment within the euro. The difficult case of Portugal", Portuguese Economic Journal 6(1): 1–21

Buiter, W, and D Lubin (2019), "Did EU membership bring economic benefits for CESEE member states?": 33-37 in I P Székely (ed) Faces of Convergence, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies.

Buti, M (2019), "Renewing the (damaged) social contract", Dahrendorf Forum, Hertie School of Governance, 9 May.

Deltuvaitė, V (2017), "Consequences of External Macroeconomic Shocks Transmission Through International Trade Channel: The Case of the Central and Eastern European Countries": 631-655 in International Conference on Applied Economics, Springer.

EBRD (2018), Transition Report 2018-2019, EBRD.

EBRD (2019), Eight Things You Should Know About Middle-Income Transition, EBRD.

European Commission (2018), "European Semester – Country-specific recommendations, Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of The Regions and the European Investment Bank", 23 May.

Hagemejer, J, and J Muck (forthcoming), "Export‐led growth and its determinants Evidence from CEEC countries", The World Economy.

Harding, T and B Smarzynska Javorcik (2011), "FDI and Export Upgrading", University of Oxford Department of Economics discussion paper 526.

IMF (2016), Taking Stocks of Monetary and Exchange Rate Regimes in Emerging Europe, IMF European Department.

Merlevede, B, and V Purice (2019), "Border regimes and indirect productivity effects from foreign direct investment", Ghent University Department of Economics working paper 965.

Milanovic, B (2016), Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Harvard University Press.

Mayer, T, and K Head (forthcoming), "Brands in motion: How frictions shape multinational production", American Economic Review.

OECD (2019), Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class, OECD.

Ossa, R (2019), "A Quantitative Analysis of Subsidy Competition in the U.S.", University of Zurich.

Szabo, S (2019), "FDI in the Czech Republic: A Visegrád Comparison, European Economy", European Commission Economic Brief 042, GD ECFIN.

Székely, I P (2019), "What difference has the EU made to the convergence process? Facets of the Faces of Convergence": 1-4 in I P Székely (ed) Faces of Convergence, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies.

Székely, I P, and M Ward-Warmedinger (2018), "Reform Reversals: Areas, Circumstances and Motivations", Comparative Economic Studies 60(4): 559-582.

Zlate, A (2016), "Offshore production and business cycle dynamics with heterogeneous firms", Journal of International Economics 100: 34-49.

Vandenbussche, H, W Connell, and W Simons (2017), "Global Value Chains, Trade Shocks and Jobs: An Application to Brexit", CEPR Discussion Paper 12303.

Wach, K, and L Wojciechowski (2016), "Determinants of inward FDI into Visegrad countries: Empirical evidence based on panel data for the years 2000–2012", Economics and Business Review, 2(1): 34-52.

Endnotes

[1] EU11 are the countries from the Baltics, Central and Eastern Europe , and the Western Balkan that joined the EU since 2004: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.