Although worries about cannabis are usually based on prevalence rates of cannabis use in the population, age of the first use of cannabis is important as well. Early onset age of cannabis may have serious short-term and long-term negative effects on individuals. Previous studies find that early cannabis use increases the intensity of use and the probability of subsequent drug use (Yamaguchi and Kandel 1984). Van Ours and Williams (2007) find using Australian data that individuals who start using cannabis early in life are less likely to quit at later ages. Van Ours (2007) finds for cannabis users in Amsterdam that quitting rates increase with the age of onset. Van Ours et al. (2013) find using data from New Zealand that early onset of cannabis use may lead to mental-health problems i.e. to suicidal thoughts.

Current cannabis policies

Cannabis policies across the world differ – cannabis use can be:

- Legal

- Illegal but decriminalised

- Illegal but unenforced, or

- Illegal

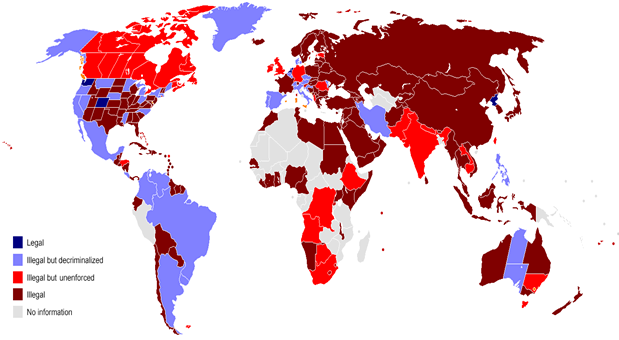

The slight difference between decriminalisation and non-enforcement is that under decriminalisation there is no legal punishment, whereas under non-enforcement there is a punishment, but this is rarely enforced. Only four states in the world have legal or quasi-legal cannabis use: the Netherlands, the states of Washington and Colorado in the US, and North Korea.1 Several European and South American countries and states in North America have decriminalised cannabis use. However, countries which forbid cannabis use still outnumber the others (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cannabis policies across the world

Source: Wikipedia.

Contrary to the general expectation that easier access will induce more use, existing empirical studies – largely focusing on medical-marijuana dispensaries in the US – fail to provide a unique conclusion on the issue. In the US, several states have medical-marijuana dispensaries which make access to cannabis easy. Cerda et al. (2012) and Wall et al. (2011) find that allowing for medical-marijuana dispensaries might have increased cannabis use. However Harper et al. (2012) and Anderson et al. (2012) show that there is no such effect. Therefore, there is not yet a consensus about the possible effects of easy access to cannabis on cannabis use.

A short history of coffeeshops in the Netherlands

Cannabis use is quasi-legalised in the Netherlands. Selling or buying small quantities of cannabis through so-called coffeeshops is not prosecuted. Drug policy in the Netherlands mainly focuses on the protection of public health (van Laar 2010) and can be summarised as ‘tolerant’ (van Solinge 1999). The basic aim of these tolerant policies is to reduce the harm done to users and their immediate environment in order to protect public health. The main drugs law of the Netherlands is the Opium Law of 1976, which introduced a distinction between soft drugs and hard drugs. The production and trade of soft drugs were considered to be much more severe offences than personal use. Possession of a small amount of cannabis was considered not as an offence but as a misdemeanour, and therefore not prosecuted. This flexibility paved the way for house dealers, which after a while turned into coffeeshops. Later on in the 1980s, the policy of tolerance of coffeeshops was publicly announced, and this announcement was followed by a sharp increase in the number of coffeeshops (Jansen 1991). In the mid-1990s, there were around 1,500 coffeeshops.

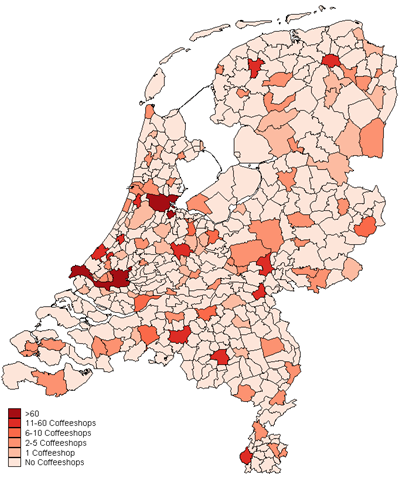

However, the 1990s also saw increased criticism of the Netherlands’ tolerant cannabis policy, both from inside the country and from other countries. The rules under which coffeeshops could operate were changed by the Dutch government in 1995. From 1996 onwards, the limit for personal possession of cannabis was decreased from 30 grams to five grams. Moreover, the monitoring and punishment of production and trade of cannabis were increased, and local governments were given the opportunity to decide whether or not they wanted to have a coffeeshop in their municipality. These more restrictive policies caused a substantial decrease in the number of coffeeshops in the country to an estimated 1,200 in the late 1990s (Bieleman et al. 2007). In 1999, the so-called ‘Damocles’ law gave more flexibility to local governments for closure of coffeeshops in their municipalities. The law resulted in a further decline in the total number of cannabis shops. In 1999 there were 846 cannabis shops across the Netherlands – a number that went down to 651 in 2011. Figure 2 shows the number of coffeeshops in each municipality in 2007.

Figure 2. Coffeeshops in the Netherlands, 2007

Source: Bieleman (2007).

Are coffeeshops tempting?

Our recent paper investigates if cannabis shops in the Netherlands have had negative spillover effects on youngsters by analysing to what extent living near a coffeeshop affects the age of onset of cannabis use (Palali and Van Ours 2013). If there was a negative spillover effect, then we would expect those who are living close to coffeeshops to have a lower age of onset of cannabis use. Table 1 below shows that the distance to a municipality with a coffeeshop seems to matter. More than half of the individuals in our sample live in, or within 5km of, a municipality that has a coffeeshop. In the young cohort, given on the left-hand side of Table 1, the individuals in this short distance range had a 40% lifetime probability of cannabis use, whereas individuals living more than 20km away from a coffeeshop had a lifetime prevalence of 16.9%.

In order to investigate whether there is indeed a causal effect from distance to cannabis use, we perform a counterfactual analysis in two parts by analysing starting ages of cannabis use of an older cohort, and starting ages of tobacco use of both cohorts. Table 1 below shows that for the uptake of tobacco, the distance to a cannabis shop does not matter. This suggests that people who live close to a cannabis shop do not have a different attitude toward use of other drugs, i.e. towards smoking. Since unobserved factors related to attitudes toward drug use would be correlated with unobserved factors behind attitudes toward smoking, this result shows that cannabis shops do not open up in neighbourhoods where people are systematically different in terms of risky health behaviours. Second, we show that the effect of distance on cannabis uptake is only present for the younger birth cohort. Individuals from an older birth cohort, given on the right-hand side of Table 1 – who grew up before the era of coffeeshops – are not affected by present-day distance to a cannabis shop.

Table 1. Distribution of distance to cannabis variable, lifetime cannabis use and lifetime tobacco use based on distance categories for young and old cohorts

This is additional evidence that coffeeshops are not located in environments where people are more likely to start using cannabis anyway. The reason is that these individuals in the old cohort were already in their mid-20s when the first coffeeshops were opened (the mid-1980s), indicating that they had already by and large made their decisions about cannabis use before the first coffeeshop was established. If there was a correlation between location of coffeeshops and general attitude of residents toward cannabis use, this would be shown in the distribution of lifetime cannabis use of the old cohort in Table 1. However, as indicated above, lifetime cannabis use percentages for the old cohort do not seem to differ across distance ranges.

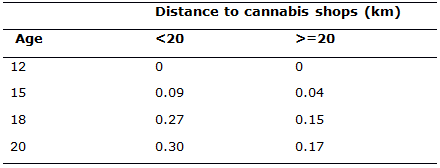

In order to provide further evidence for our preliminary findings, we analyse the starting age of cannabis use and tobacco use for young and old cohorts by using duration models. In these models we control both observable and unobservable characteristics that would affect uptake of cannabis. After an extensive examination of the results, we conclude that those who live within 20 km of a coffeeshop start using cannabis at earlier ages. We find that the starting age of cannabis use in the old cohort and the starting age of tobacco use in both cohorts are unaffected by the distance to cannabis shops. Based on our baseline parameter estimates, Table 2 below presents the results of a simulation exercise showing the effect of the distance variable on the probability of using cannabis at a specified age. We find that those who live far away from coffeeshops have a lower probability at any age.

Table 2. Simulation results showing the effect of distance to coffeeshops

The results above confirm the fear that availability of cannabis at Dutch coffeeshops has an adverse spillover effect on youngsters. Does such a finding immediately suggest that it is better to close coffeeshops? Not necessarily so. Even though we find that youngsters who live closer to coffeeshops display a lower uptake age, we cannot conclude that there is a welfare loss induced by the coffeeshops. There are numerous other factors that need to be taken into consideration, such as the intensity of use, the uptake of hard drugs and the effects of an uncontrolled environment. Our study does not provide evidence on how the intensity of cannabis use might be affected by the existence of cannabis shops. Furthermore, we would expect the closure of all cannabis shops to lead some potential users to go on the black market in search of cannabis, where they will be more likely to come across dealers of hard drugs. All in all, although existence of coffeeshops seems to have an adverse effect on the uptake of cannabis among youngsters, this is insufficient reason to advocate closure of coffeeshops.

References

Anderson, D M, B Hansen, and D I Rees (2012), “Medical Marijuana Laws and Teen Marijuana Use”, unpublished.

Bieleman, B, A Beelen, R Nijkamp, and E de Bie (2007), “Coffeeshops in Nederland. Aantallen en gemeentelijk beleid in 2007” (“Coffeeshops in the Netherlands. Numbers and local policy in 2007”), Groningen: Intraval.

Cerdá, M, M Wall, K M Keyes, S Galea, and D Hasin (2012), “Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: Investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence”, Drug and Alcohol Dependence 120: 22–27.

Harper, S, E C Strumpf and J S Kaufman (2012), “Do medical marijuana laws increase marijuana use? Replication study and extension”, Annals of Epidemiology 22: 207–212.

Jansen, A (1991), Cannabis in Amsterdam. A geography of hashish and marihuana, Countinho.

Palali, A and J C van Ours (2013), “Distance to cannabis-shops and age of onset of cannabis use”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 9632.

Van Laar, M (2011), Nationale Drug Monitor, Trimbos Instituut, Utrecht.

Van Solinge, T (1999), “Dutch drug policy in a European context”, Journal of Drug Issues 29(3): 511–528.

Van Ours, J C (2007), “Cannabis use when it’s legal”, Addictive Behaviors 32: 1441–1450.

Van Ours, J C and J Williams (2007), “Cannabis prices and dynamics of cannabis use", Journal of Health Economics 26: 578–596.

Van Ours, J C, J Williams, D Fergusson, and L Horwood, “Cannabis use and suicidal ideation”, Journal of Health Economics 32: 524–537.

Wall, M M, E Poh, M Cerda, K M Keyes, S Galea and D S Hasin (2011), “Adolescent marijuana use from 2002 to 2008: higher in States with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear”, Annals of Epidemiology 21: 714–716.

Yamaguchi, K and D B Kandel (1984), “Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: III. Predictors of progression”, American Journal of Public Health 74: 673–681.

1 Recently, the parliament in Uruguay approved a law that will legalise cannabis.