Education is good for longevity. A large literature shows that an individual’s own schooling is the most important predictor of his or her health. Parents’ schooling, especially mother’s schooling, is also the most important predictor of children’s health.1 This finding emerges whether health levels are measured by mortality rates, morbidity rates, self-evaluation of health status, or physiological indicators of health, and whether the units of observation are individuals or groups. Improvements in child health are widely accepted public policy goals in developing and developed countries. The positive correlation between mother’s schooling and child health in numerous studies was one factor behind the World Bank’s campaign in the 1990s to encourage increases in maternal education in developing countries.2 Angus Deaton argues that policies to increase education in the US and to increase income in developing countries are very likely to have larger payoffs in terms of health than those that focus on health care, even if inequalities in health rise.3 Since more education typically leads to higher income, policies to increase the former appear to have large returns for more than one generation throughout the world.

Efforts to improve health by increasing the amount of formal schooling assume that more schooling causes better health. A number of investigators have argued, however, that reverse causality from health to schooling or omitted “third variables” may cause schooling and health to vary in the same direction. The third-variable hypothesis has received the most amount of attention in the literature. For example, Victor Fuchs identifies time preference as the third variable.4 He argues that persons who are more future-oriented attend school for longer periods of time and make larger investments in their own health and in the health of their children. Thus, the effects of schooling on these outcomes are biased if one fails to control for time preference.

Governments can employ a variety of policies to raise the educational levels of their citizens. These include compulsory schooling laws, new school construction, and targeted subsidies to parents and students. If proponents of the third-variable hypothesis are correct or if health causes schooling, evaluations of these policies should not be based on studies that relate adult health or child health to actual measures of schooling because these measures may be correlated with unmeasured determinants of the outcomes at issue.

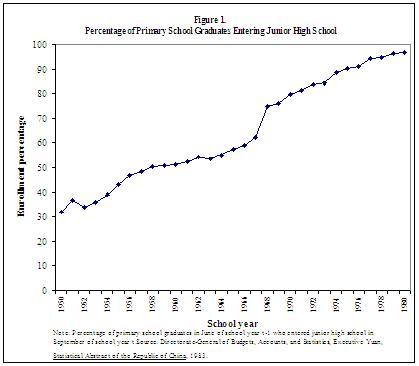

In our research we use techniques that control for the reverse causality and third-factor effects. We evaluate the effects of a policy initiative that radically altered the school system in Taiwan and led to an increase in the amount of formal schooling acquired during a period of very rapid economic growth.5 In 1968 Taiwan extended compulsory schooling from six years to nine years. To accommodate the expected increase in enrollment in junior high schools due to the legislation, the Taiwanese government opened 150 new junior high schools, an increase of almost 50 percent, at the beginning of the school year 1968-69 (September 1, 1968). This education reform created the largest expansion in junior high school construction and student enrollment in Taiwan’s history. This increased the number of junior high schools from 0.3 schools per thousand children ages 12 through 14 in the school year 1967-1968 to 0.4 schools per thousand children in that age range in the school year 1968-1969. The immediate impact was to increase the percentage of primary school graduates who entered junior high school from 62 percent in 1967 to 75 percent in 1968 (see Figure 1). By 1973, an additional 104 public junior high schools had opened, increasing the total number of these schools from 311 in 1967 to 565 in 1973 (0.5 per thousand children ages 12-14). The junior high school entry percentage rose to 84 percent in the same year. Hence, the number of junior high schools almost doubled in a six-year period, the number per thousand children ages 12 through 14 rose by almost 70 percent, and the junior high school entry percentage grew by 35 percent. A notable aspect of the school construction program was that its intensity varied across regions of Taiwan.

This compulsory schooling legislation provides a “natural experiment” that helps us evaluate the impacts of parents’ schooling on the health of their children. Citizens who were between 13 and 20 years old when the new law took effect were unlikely to be affected by school reform and constitute the ‘control group’. Those under 12, by contrast, were very likely to have been affected by school reform and constitute a ‘treatment group’. Moreover, the effects of school reform on the number of years of formal schooling completed in the treatment group should be larger the larger is the program intensity measure in city or county of birth.

Greater intensity among younger cohorts should lead to more schooling but should be uncorrelated with unmeasured determinants of the well-being of the offspring of these cohorts.6 We find that compulsory school reform increased the number of years of formal schooling obtained by women in the treatment group by amounts ranging from 0.25 years to almost 1 year. Comparable increases by men in the treatment group range from 0.2 years to 0.6 years. The next step is to look at the impact of these increases on the health of infants born to women in the treatment group or to the wives of men in that group in the period from 1978 through 1999. We examine four outcomes: the percentage of low-weight (less than 2,500 grams) births, the neonatal mortality rate (deaths of infants within the first 27 days of life per thousand live births), the postneonatal mortality rate (deaths of infants between the ages of 28 and 364 days of life per thousand infants who survive the neonatal period), and the infant mortality rate (deaths of infants within the first 364 days of life per thousand live births).

Increases in mother’s schooling due to the 1968 legislation and its aftermath had statistically significant negative effects on each of the four outcomes. These effects were larger in absolute value and more significant than those due to expansions in father’s schooling. The percentage of under-weight births fell by approximately 0.20 percentage points due to the rise in mother’s schooling. This translates into a percentage reduction of 4.74 percent in a fixed population. Reductions in mortality ranged from a decline of 0.20 neonatal deaths per thousand live births to a decline of 0.77 infant deaths per thousand live births. In percentage terms, the smallest decline is an 8.41 percent fall in the number of neonatal deaths. The largest decline is an 18.63 percent reduction in the number of postneonatal deaths. In all, the increase in mother’s schooling associated with the reform saved almost 1 infant life in 1,000 live births, resulting in a decline in infant mortality of approximately 11 percent.

In one sense it is not surprising that mother’s schooling is a more important determinant of infant health outcomes than father’s schooling given the role of the mother in the prenatal and neonatal periods and the much lower likelihood that mothers work in the postneonatal period. The finding is related to the historical role of the mother as the family member most involved with children. The importance of mother’s schooling relative to father’s schooling should not, however, be viewed as a foregone conclusion. Historically, fathers have made much larger contributions to family income than mothers, especially since they have been more likely to work in the labor market. Since earnings are so dependent on schooling, father’s schooling might dominate mother’s schooling in infant health outcomes if the schooling effect simply reflected command over real resources. Our results suggest that this is not the case.

Conclusion

We used a natural experiment in Taiwan to ask: Does an increase in parental schooling improve infants’ health? Our answer to this question is yes. Moreover, mother’s schooling is a more important than father’s schooling – suggesting that the mechanism connecting education and health is not solely related to income.

Perhaps the most important implication of our results is that they suggest substantial payoffs in terms of health to efforts by developing countries to increase the amount of compulsory schooling and invest more resources in the educational sector.

Footnotes

1 See, for instance, Grossman, 'M. Education and non-market outcomes' In Vol. 1, edited by E Hanushek and F Welch. Amsterdam: North-Holland, Elsevier Science, 577-633, 2006.

2 World Bank. World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

3 Deaton, A. 'Policy implications of the gradient of health and wealth'. Health Affairs 2002, 21(1): 13-30.

4 Fuchs, VR. Time preference and health: an exploratory study. In Economic Aspects of Health, edited by VR Fuchs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 93-120, 1982.

5 This commentary is based on “Parental Education and Child Health: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Taiwan”, NBER Working Paper No. 13466.

6 In other words, we employ the products of cohort indicators and a geographical program intensity measure as instruments for schooling.