On 23 June 2016, the UK voted to leave the EU and pursue new trading arrangements with the EU and the rest of the world. The EU is the UK's largest trade and investment partner. About half of the UK's cross-border flows of goods and services are with the EU, and membership determines the provisions of a vast number of policies and regulations related to these areas.

Much of the discussion of future trading arrangements has focused on whether the UK should continue to have tariff-free trade with the EU, say, by staying in the European Free Trade Area or the EU's customs union (House of Commons 2017). As the Article 50 time period draws to a close, there is growing recognition that for a developed economy like the UK, tariff-free market access is just one of a number of provisions that are needed to ease cross-border trade with both the EU and the rest of the world.

Modern trade agreements go beyond tariff reductions

About 280 new trade agreements have entered into force in the last 26 years. And the large majority of modern agreements have gone beyond tariff reductions. They include a range of new provisions that set rules in areas such as market access, regulation of foreign service providers, and promoting competition among domestic and foreign businesses. Such trade agreements are often called ‘deep trade’ agreements.

Despite a growing literature that examines the impact of deep trade agreements on trade flows (e.g. Baier et al. 2014, Mattoo et al. 2017, Mulabdic et al. 2017), little research examines which specific provisions contribute the most to expansion in bilateral trade. Disentangling the relative contribution of deep provisions is relevant for the design of new trade agreements. After Brexit, the UK will have to negotiate which provisions to include in its new arrangements, and a fundamental question is which of these are most important in reducing the non-tariff barriers to trade.

Deep provisions in modern trade agreements

In recent empirical work, we study the impact of deep provisions on bilateral trade of goods and services using a gravity model (Dhingra et al. 2018). This work differs from most studies, which measure trade agreement depth without distinguishing between specific provisions. We look at the contribution of different trade agreement provisions on bilateral trade flows as countries start implementing new agreements and provisions with their partners.

As production networks have become fragmented and dispersed, we examine the impact of different provision categories on gross trade and value-added trade of intermediate and final goods and services separately, at aggregate and sectoral levels. Despite services being the biggest sector in most developed economies, the majority of research on the impact of trade agreements has focused on trade in goods, due to limited data on cross-border services flows. Disaggregating gross trade data for all sectors in the 2016 release of the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) into value-added components, we are able to look at both goods and services trade, and the extent to which they contain domestic value-added.

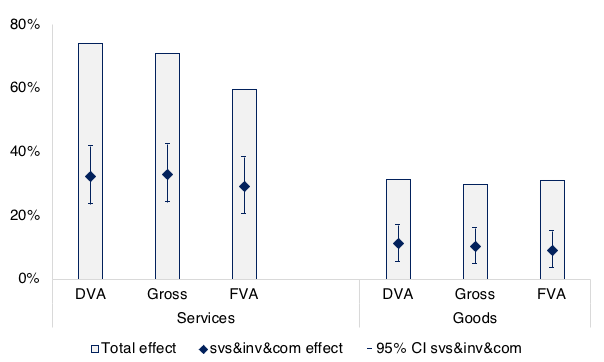

Deep provisions give a big extra boost to trade, and even bigger to domestic value added in services

At the aggregate level, we find that trade agreements with deep provisions have the largest impact on domestic value added, and that services, investment, and competition provisions contribute roughly 50% to the overall impact of trade agreements on trade in services, and between 30% and 35% on trade in goods (Figure 1). These results hold regardless of whether the goods or services are intermediates or final. Moreover, these findings are robust to the inclusion of additional provision categories, which, alongside services, investment, and competition provisions, encompass the universe of underlying clauses that make up deep agreements.

Figure 1 Relative impact of services, investment, and competition provisions

Source: Dhingra et al. (2018).

At the sector level, we find that the impact of provisions related to services, investment, and competition on both gross and value-added trade is statistically significant for the large majority of sectors, and thus positively contributes to the total effect of deep agreements on trade flows. Our results also indicate that the services sectors that see the biggest benefits from services, investment, and competition provisions are those that are most important for supply chain integration, such as transportation and storage (which helps with the timely delivery of goods). Moreover, we find that the financial and insurance activities sector benefits from these deep non-tariff provisions, even though it is not sensitive to the tariff cuts inherent in a trade agreement.

Policy exercise for future UK trade deals

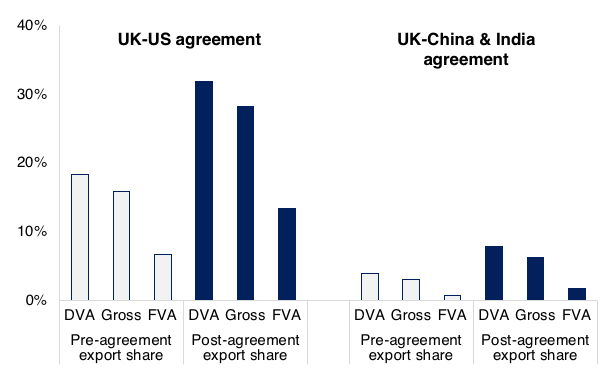

We use the results of our sectoral regressions to determine how the composition of the UK's bilateral exports might change after entering into a deep agreement with new partners. We examine two hypothetical free trade agreements – a bilateral deal with the US, and bilateral deals with China and India. These countries are among the UK's largest non-EU trading partners (and received its largest share of non-EU exports in 2014 – the last year for which we have trade data in our study).

In both cases, we find that in a post-agreement scenario, the UK’s services exports increase on the whole, relative to manufacturing exports, and that the domestic value-added component of sectoral trade would rise more than its gross or foreign value-added flows. We also find that the services sector that gains in particular is that of professional, scientific, and technical activities (Figure 2). In the case of a UK-US agreement, we estimate exports in this sector to rise by roughly two thirds of their 2014 share in total exports. In the case of an agreement between the UK and China/India, we estimate exports in this sector to double.

Among other industries, the professional, scientific, and technical activities sector covers scientific research and development as well as marketing research. As such, our results suggest that the UK’s entry into a deep trade agreement with either the US or China/India that encompasses non-tariff liberalisation of services, investment, and competition can increase economic activity in industries that are key to its innovative activity, and that foster engagement in high-value stages of supply chains.

Figure 2 Estimated change in professional, science and technological services exports

Source: Dhingra et al. (2018).

References

Baier, S L, J H Bergstrand, and M Feng (2014), “Economic integration agreements and the margins of international trade”, Journal of International Economics, 93 (2), 339-350.

Dhingra, S, R Freeman, and E Mavroeidi (2018), “Beyond tariff reductions: What extra boost to trade from agreement provisions?”, LSE Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper 1532.

House of Commons International Trade Committee (2017), “UK trade options beyond 2019”, First Report of Session 2016–17, p.4.

Mattoo, A, A Mulabdic, and M Ruta (2017), “Trade creation and trade diversion in deep agreements”, World Bank Working Paper 8206.

Mulabdic, A, A Osnago, and M Ruta (2017), “Deep integration and UK-EU trade relations”, World Bank Working Paper 7947.