Artificial intelligence (AI) is one of the most important technological advances of our era. Recent progress in AI and, in particular, machine learning has dramatically increased predictive power in many areas such as speech recognition, image recognition, and credit scoring (Agrawal et al. 2016, Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2014, Mullainathan and Spiess 2017). Unlike the last generation of information technology that required humans to codify tasks explicitly, machine learning is designed to learn the patterns automatically from examples (Brynjolfsson and Mitchell 2017). Because this capability potentially affects so many parts of the economy, AI has been called a general purpose technology, just as the steam engine and electricity. If this is true, then AI should ultimately lead to fundamental changes in work, trade, and the economy.

However, empirical evidence documenting concrete economic effects of using AI is largely lacking. In particular, contributions from AI have not been found in measures of aggregate productivity. Brynjolfsson et al. (2017, 2018) argue that the most plausible reason for the gap between expectations and statistics is due to lags in complementary innovations and business procedure reorganisation. If the gap is indeed due to lagged complementary innovation, the best domains to empirically assess the impact of AI are settings where AI applications can be seamlessly embedded in an existing production function. In particular, various digital platforms are at the forefront of AI adoption, providing ideal opportunities for early assessment of AI’s economic effects.

In a recent paper (Brynjolfsson et al. 2018b), we provide evidence of direct causal links between AI adoption and economic activities by analysing the effect of the introduction of eBay Machine Translation (eMT) on eBay’s international trade. As a platform, eBay mediated more than $14 billion of global trade among more than 200 countries in 2014. The focal AI technology, eMT, is an in-house machine learningsystem that statistically learns how to translate among different languages from different language sources. These machine learning models are trained on both eBay data and other data automatically scraped from the web[EN1] .Some hand-crafted rules are also applied, such as preserving named entities (e.g. numbers and product brands), so that eMT is more suited for the existing eBay environment.eMT is optimised to work in real-time, yielding high-quality translations within milliseconds. We exploit the introduction of eMT for several language pairs, most notably English–Spanish, as natural experiments, and study their consequences on US exports on eBay.

Results

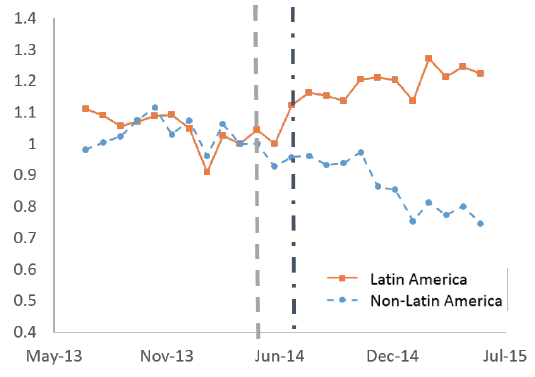

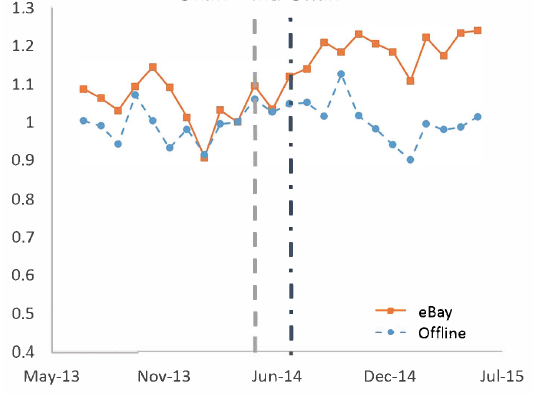

To identify the effect of machine translation, we compare the post-policy change in US exports to the treated countries with the change in exports to the control countries. The treated countries are Spanish-speaking Latin American countries. Our main control group consists of all other countries that US sellers export to on eBay. In Figure 1a, we show parallel trends between the two groups. Using this control group, we find that eMT increases US exports on eBay to Spanish-speaking Latin American countries by 17.5%.

Figure 1 Parallel trends assumption

a) US exports on eBay, Latin America and non-Latin America

b) US exports to Latin America, online and offline

Notes: Exports in Figure 1a are measured in quantity and normalised to the level in April 2013. Exports in Figure 1b are measured in dollars and normalised to the level in April 2013. The dashed and dot-dashed lines indicate the introduction of query and item title translations, respectively.

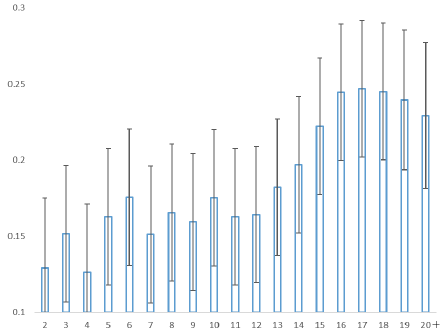

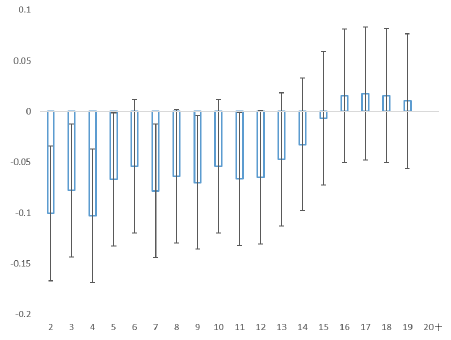

More interestingly, we identify the following heterogeneous treatment effects: the increase in exports is more pronounced for (1) products with more words in listing titles, (2) differentiated products, (3) cheap products, and (4) less experienced buyers. Each of these effects is consistent with a causal effect of translation. First, translation-related costs should generally increase with the number of words. Second, differentiated products (such as antiques, jewellery, and clothing) have more variation in product attributes. Therefore, translation-related search costs should be higher for differentiated products because of higher language requirements (and hence higher translation costs) of translating the specifics of these products into local languages. Third, the fixed costs of translation are higher as a fraction of item value for cheap items. Lastly, inexperienced buyers generally spend less time on eBay, and have high search costs and likely high costs for alternatives to eBay’s translation. In each case, the heterogeneous effects are consistent and suggest that the benefits of machine translation are greater in categories where language barriers were higher to begin with.

Identification

To causally identify the effect of machine translation on international trade on eBay, we face two challenges. First, eMT may confound with other contemporaneous marketing activities in treated countries. We mitigate this concern in three ways. First, we narrow the estimation window to +/-4 weeks and +/-2 weeks of eMT’s introduction to minimise potential confounding effects, and find similar estimates. Second, we show that exports increase more for listings with longer titles (Figure 2). This strongly suggests that larger exports are due to reduced translation costs, provided that eBay’s marketing activities are independent of title length. Lastly, if the increased sales were due to some unobserved marketing activities,we would expect a general increase in the number of new eBay buyers. However, we do not observe any such increase during or shortly after the introduction of eMT.

Figure 2 Export increase by number of words in listing titles

a) Export increase by no. or words in titles

b) Difference relative to titles with 20+ words

Notes: Figure 2a: treatment effects interacted with different title lengths. Figure 2b: treatment effects relative to listings with 20+ words. The bars represent 95% confidence intervals. ‘20+’ on the x-axis includes listings with 20 or more words in the title.

The second identification challenge is the validity of the control group. To address this, we show parallel trends between the two groups both graphically and in a leads-and-lags regression. We do not identify any significant difference between exports to the treatment and control countries prior to the introduction of eMT. Next, to mitigate spillover effects after the policy change, we adopt a second control group – overall US exports (online and offline exports) to the affected countries – and obtain similar estimates. Lastly, we exploit eMT‘s rollouts in the EU and Russia in different months, and estimate comparable eMT effects for other language pairs: English–French, English–Italian, and English–Russian. The large effect across languages is consistent with AI being a general purpose technology.

Takeaway

Our results have two main implications. First, language barriers have greatly hindered trade, especially among small enterprises. This is true even for digital platforms where trade frictions are already smaller than offline trade. In our study, the introduction of eMT on eBay generated an export increase of 17.5% in quantity and 13.1% in revenue. This is consistent with research by Lohmann (2011) and Molnar (2013), who argue that language barriers may be far more trade-hindering than suggested by previous literature. Because it is impossible to easily change the language spoken by millions of inhabitants of different trade partner countries, and because language is often confounded with other cultural similarities, prior research has had difficulty identifying the specific effects of language on trade. However, the introduction of eMT provides a natural experiment to assess the importance of language as a trade barrier.

To put our result in context, Lendle et al. (2016) have estimated that a 10% reduction in distance would increase trade revenue by 3.51% on eBay. This means that the introduction of eMT is equivalent to an export increase from reducing distances between countries by 37.3%. Furthermore, Hui (2018) has estimated that removal of administrative and logistic export costs increased export revenue on eBay by 12.3% in 2013, which is less than the effect of eMT. These comparisons suggest that the trade-hindering effect of language barriers is of first-order importance. Machine translation has made the world significantly more connected and effectively smaller.

Second, our findings demonstrate that AI is already affecting productivity and trade, and it has significant potential to increase them further. Besides machine translation, AI applications are also emerging in other fields such as speech recognition and computer vision, with applications ranging from medical diagnosis and customer support to hiring decisions and self-driving vehicles. As the new applications are introduced online, they will provide new opportunities to assess the economic impact of AI via natural experiments such as the one we examined in this paper.

References

Agrawal, AK, JS Gans and A Goldfarb (2018), “Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence: Prediction versus judgment”, NBER Working Paper No. w24626.

Brynjolfsson, E, and A McAfee (2014), The Second Machine Age: Work, progress and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies, Norton.

Brynjolfsson, E, and T Mitchell (2017), “What can machine learning do? Workforce implications”, Science 358(6370): 1530-1534.

Brynjolfsson, E, D Rock and C Syverson (2017), “Artificial intelligence and the modern productivity paradox: A clash of expectations and statistics”, in Economics of Artificial Intelligence, University of Chicago Press.

Brynjolfsson, E, D Rock and C Syverson (2018a), “The productivity J-curve: How intangibles complement general purpose technologies”, working paper, MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy.

Brynjolfsson, E, X Hui and M Liu (2018), “Does Machine Translation Affect International Trade? Evidence from a Large Digital Platform”, NBER Working Paper 24917.

Hui, X (2018). “E-commerce platforms and international trade: A large-scale field experiment”, SSRN.

Lendle, A, M Olarreaga, S Schropp and PL Vézina (2016). “There goes gravity: eBay and the death of distance”, The Economic Journal 126(591): 406-441.

Lohmann, J (2011). “Do language barriers affect trade?”, Economics Letters 110(2): 159-162.

Molnar, A (2013). “Language barriers to foreign trade: Evidence from translation costs”, working paper, Vanderbilt University.

Mullainathan, S, and J Spiess (2017). “Machine learning: An applied econometric approach”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(2): 87-106.