For years, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has bought Japanese stocks as part of its massive monetary easing programme to lift the country out of deflation, and hit a 2% price stability target (Nangle and Yates 2017). Under Governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing package, stock-buying was begun as a monetary easing tool – in April 2013 at a pace of about ¥1 trillion annually, expanding to about ¥3 trillion in October 2014, and further to about ¥6 trillion in July 2016 (Shirai 2018a). The purpose was to increase aggregate demand and thus inflation, as well as to encourage Japanese savers to take on more risk by buying equities.

Unprecedented stock purchases as an monetary easing tool

The current exchange-traded fund (ETF) purchases are different from the past two practices conducted by the BOJ where banks’ stocks were purchased directly for financial system stability purposes – in 2002–2004, when Japan suffered a domestic banking crisis, and in 2009–2010, during and after the Global Crisis. The BOJ purchased stocks worth only about ¥2 trillion in 2002–2004 and about ¥400 billion in 2009–2010.

Some central banks do purchase foreign stocks and ETFs as part of their foreign reserve management strategies. Such purchases should be distinguished from the practices adopted by the BOJ, as the BOJ has focused on domestic stocks (stocks listed on the domestic stock markets). Central banks in emerging economies usually attempt to hold ample foreign reserve assets in preparation for volatile cross-border capital flows. In recent years, they have diversified their portfolio including risky assets to increase returns in the extremely low interest rate environment. Among advanced economies, the Swiss National Bank has intervened heavily in the foreign exchange markets since the Global Crisis, as the Swiss franc appreciated sharply due to its status as a safe haven currency. Given the limited amount of government bonds issued, the Swiss National Bank has found it necessary to intervene in the foreign exchange markets rather than conduct unconventional quantitative easing through government bond purchases. Diversification of resultant accumulated foreign reserve assets is sought through purchasing various foreign assets including stocks. While the monetary policy meeting of a central bank determines the types and the amount of assets to be purchased to achieve its price stability mandate, foreign reserve management is generally conducted by professional external (private sector) reserve managers appointed by a central bank according to some strategic benchmarks set by the central bank.

There are very few central banks in the world that have purchased stocks on this scale and for such a long time as part of the conduct of monetary policy. So, when the BOJ embarked on its course of action, it had no reference to the experiences of other central banks. Similarly, the BOJ’s extremely challenging task of normalising the policy and ultimately disposing of the stocks purchased is without precedent.

The BOJ’s ETF purchases contributing to higher stock prices

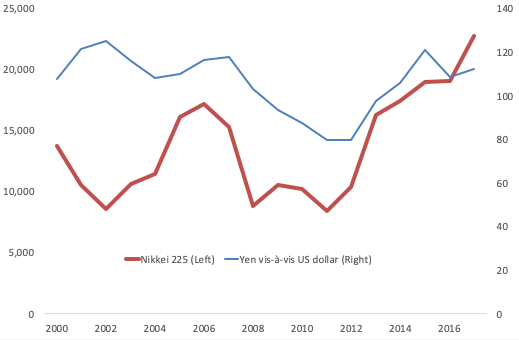

Stock prices began to rise from late-November 2012 in anticipation of the BOJ’s aggressive monetary easing – although they have never exceeded the peak recorded in late-December 1989 (Figure 1). Stock prices rose through various domestic and foreign channels. Domestic channels include the BOJ’s monetary easing (through a decline in short- and long-term interest rates, ETF purchases, and depreciation of the yen), as well as favourable corporate profits, which are also partially supported by the BOJ’s policy. Foreign channels include higher US stock prices and the appreciation of the US dollar against major currencies. There is generally a positive correlation between the exchange rate and stock prices as the yen’s depreciation contributes to higher yen values of foreign profits earned by Japanese multinational firms (Figure 2). Given that those multinational firms are listed on the stock market, the higher consolidated profits led to higher stock prices.

Figure 1 The Nikkei 225 stock market index (¥) and TOPIX index

Source: Bloomberg.

Figure 2 The yen vis-à-vis the US dollar and Nikkei 225 (¥)

Sources: Bloomberg; Bank of Japan.

Why has the price-earnings ratio declined?

Meanwhile, the BOJ’s heavy involvement in the stock market has invited much discussion in Japan, having given rise to the following five issues.

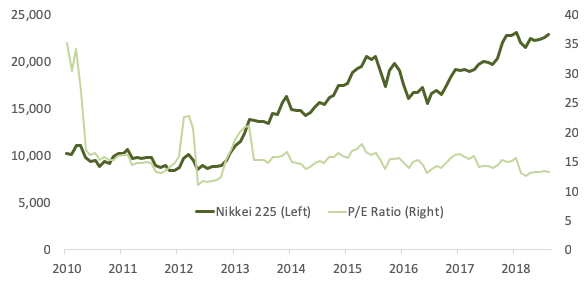

First, the current stock prices have risen but not in proportion to current profits. The peak of the stock price bubble in late-December 1989 was excessive because the price–earnings ratio (P/E ratio) was about 80 times, for example, that of the Nikkei 225. The P/E ratio of the Nikkei 225 fluctuated within a range of 14–16 times in 2014-17 — the level generally regarded as appropriate; however, it has since declined to around 13 times (Figure 3). The fact that stock prices have so far not regained their maximum level suggests that the profits of listed firms have not been strong enough to reach the maximum stock prices recorded in 1989 after the bubble burst. It also gives investors the impression that capital gains are unlikely to be large, which may deter new investors. While this could indicate that Japanese stock prices have become somewhat underpriced despite the BOJ’s ETF purchases, this could be associated with market participants’ negative outlook on future corporate profits as compared with current profits. Corporate profits began to rise steadily in 2013, reflecting the yen’s depreciation, public investment mainly related to the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, real estate development activities in the metropolitan areas, and lower oil prices in 2014–16. Corporate profits recorded their highest level in 2017, although the pace of increase relative to the previous year was moderate. The level of corporate profits for 2018 is widely expected to be lower than that of 2017.

Figure 3 Nikkei 225 (¥) and P/E ratio

Source: Bloomberg.

Greater impact on stock prices of small-cap companies

Second, ETF buying may lead to the possible overvaluation of some small-capitalisation stocks, particularly those included in the Nikkei 225. BOJ’s ETF purchases tended to favour stocks included in the price-weighted Nikkei 225 Stock Average as compared with the market value-weighted TOPIX. The TOPIX covers 2,106 firms listed in the Tokyo Stock Exchange First Section, whereas the Nikkei 225 covers only 225 listed firms. As some small-cap firms are included in the Nikkei 225 with higher weights due to their relatively higher stock prices, the continuation of the BOJ’s purchases tended to generate an overvaluation of such stocks. A famous example was Fast Retailing Co., owner of the well-known apparel chain Uniqlo, whose weight accounts for 7.5% of the Nikkei 225 Stock Average while accounting for only 0.3% of the TOPIX. The P/E ratio of Fast Retailing Co. is around 38 times as of August 2018 – much higher than the 13.5 times in the case of the Nikkei 225 and 18 times in the case of the Tokyo Stock Exchange First Section.

While the BOJ adjusted its purchases to take account of such risks by increasing purchases of TOPIX-related ETFs and reducing purchases of Nikkei 225-related ETFs in September 2016 and further in July 2018, the problems remain. Small-cap shares will likely face a sharp sell-off when the BOJ begins to reduce ETF purchasesand sell those stocks. Figure 4 depicts the movements in the stock prices of Fast Retailing Co. as well as the retail sector (to which Fast Retailing Co. belongs). The chart shows that the stock price of Fast Retailing Co. has been higher than the retail sector trend since 2013, especially when the retail sector stock prices (also the overall stock prices) have shown a rising trend. While there may be other firm-specific factors contributing to this gap, the stock price could be overpriced partly as a result of the BOJ’s purchases of Nikkei 225-related ETFs.

Figure 4 Stock prices of Fast Retailing Co. and retail sector

Source: Bloomberg.

Growing presence as a major investor and corporate governance

Third, ETF buying may have not only reduced downside risk on all stocks purchased but also may have adverse impacts on corporate governance. The BOJ’s holdings of ETFs recorded about ¥21 trillion on a book value basis as of August 2018. The BOJ could be the third largest shareholder of listed shares after the Government Pension Investment Funds and Blackrock, which hold Japanese stocks worth about ¥41 trillion and ¥30 trillion on a market value basis, respectively, as of June 2018. The Government Pension Investment Funds manages about ¥163 trillion of the Reserve Funds of the Government Pension Plans, making it one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world. Nikkei Newspaper reported on 17 June 2018 that the BOJ has become one of the top 10 largest shareholders in about 40% of listed firms as of the end of March 2018 (Table 1). Of these, the BOJ has become the major shareholder in five listed companies including Fast Retailing Co., when only floating shares are taken into account. For example, the BOJ holds about 17.5% of the total number of shares issued, but this ratio becomes much higher, namely 70%, in terms of floating shares. Some concerns have been raised by market participants over the BOJ’s substantial purchases of ETFs, since the central bank has become one of the largest shareholders of listed stocks on a per-investor basis, with no voting rights being exercised. In the worst case, this may delay necessary corporate restructuring, undermine labour productivity growth and hurt potential economic growth.

Table 1 TheBOJ’s stock holding shares (%)

Source: Nikkei, 27 June 2018.

Limited portfolio rebalancing among individuals

Fourth, individuals remain highly risk-averse and did not actively rebalance their portfolios in favour of risk assets. Their holding of cash and deposits as a share of total financial assets (about ¥1,800 trillion) have recorded more than 50% before and after the Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing programme. Japan’s stock market has been increasingly dominated by foreign investors as a group in terms of the outstanding amount of holdings (Figure 5). Also, foreign investors as a group dominate stock purchasing and selling transactions, accounting for about 60–70% of all the transactions over the past five years – in contrast with individual investors, who remained inactive except in 2013 (Shirai 2018b).

Figure 5 Stock holdings by investor types (trillions of ¥)

Source: Japan Exchange Group.

Complicated process of normalisation of monetary easing

Fifth, the BOJ’s ETF purchases make the exit strategy complicated. Given that it is likely to take a long time to achieve 2% inflation, because underlying inflation remains weak (consumer price inflation was at just 0.2% in August 2018 after excluding all food and energy), the BOJ may find it necessary to unwind ETF purchases from the annual pace of about ¥6 trillion. Leaving room for additional monetary accommodation in the event of recession is also essential. The BOJ has decided to make an adjustment to its ETF purchases in July 2018 — purchasing more flexibly depending on stock market conditions while sticking to the official annual purchase plan of about ¥6 trillion. This suggests that the BOJ intends to cope with the side-effects of its buying and possibly prepare for ‘stealth tapering’ as it is with its government bond-buying program. Tapering the amount of ETF purchase must be carefully conducted as the potential impact on stock prices remains large. For the time being, the central bank should tacitlybegin to reduce the annual pace of ETF purchases toward about ¥3 trillion – the level before the 2016 expansion, while maintaining the official annual target of ¥6 trillion. It is better to reduce ETFs now when corporate profits are high and the economy is expanding than in adverse conditions. A cut in ETF purchases toward zero may be challenging since the ETF purchases are part of the Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easingprogram.

Before taking any clear steps toward monetary policy normalisation, the BOJ should introduce flexibility in interpreting the 2% price stability target. It should incorporate the 1% upper and lower range (±1%) of the target into the 2% target itself.The BOJ and the government would then not need to abandon the 2% target while in practice aiming at a 1% figure that would be acceptable to the public. Such flexibility would be better than lowering the target from 2% to 1% since many central banks have begun to interpret the 2% price stability more flexibly. For example, Sweden’s Riksbank adopted ±1% target range into the 2% target in 2017.Dr Eric Rosengren, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, has suggested the adoption of an inflation range in the US since a rate of optimal inflation may be uncertain and unfixed like the natural rate of unemployment (Rosengren 2018). Moreover, a scheduled increase in the consumption tax in October 2019 from 8% to 10% is expected to generate inflation above 2% for a year. That gives officials the opportunity to introduce a 1% to 3% inflation target range that could be favourably presented to the public.

Once the price stability target becomes more flexible, the BOJ may be able to reduce ETF purchases more clearly. It could also then expand the target range for yields on 10-year bonds further from the current ±0.2% range and reduce Japanese government bond purchases to the level of net issuance (about ¥20 trillion annually). Completing the process of tapering out purchases of ETFs and bonds, and eliminating the 10-year yield target may take much longer since the Japanese economy may face an economic slowdown after the scheduled consumption tax hike in October 2019 and the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. So, the full normalisation of monetary policy, notably raising short-term interest rates, is difficult to forecast. It will be some time before the BOJ can follow the US Federal Reserve. But it could and should start reducing the distortions caused by stock buying much earlier.

References

Nangle, T and A Yates (2017) “Quantifying the effect of the Bank of Japan’s equity purchases,” VoxEU.org, 12 October.

Rosengren, E S (2018), “Reviewing monetary policy framework,” Remarks at a Forum on the Federal Reserve’s Inflation Target, the Brookings Institution, Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, 8 January 2018.

Shirai, S (2018a), “Mission incomplete: Reflating Japan’s economy,” Asian Development Bank Institute, second revision.

Shirai, S (2018b), “Bank of Japan’s Exchange-Traded Fund purchases as an unprecedented monetary easing policy”, Asian Development Bank Institute, Working paper no 865.